ALTERNATIVE EDUCATION

With ‘bespoke’ solutions, London’s Gateways offers vocational training to Jewish students who struggle in mainstream schools

Marking 10 years in operation, the nonprofit is looking to expand, both to the Manchester Jewish community and to the wider British public

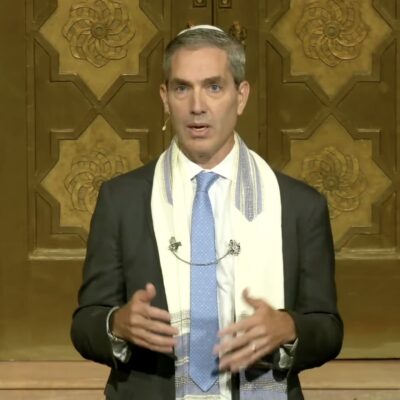

COURTESY/GATEWAYS

Alumna Elianna Green speaks about her experiences at the Gateways school in London, in an undated photograph.

LONDON — Gateways sits quietly in a one-story building on a suburban street in the northwest of the city, roughly halfway between the Jewish neighborhoods of Golders Green and Edgware.

Dominating the entry area, with its breakout spaces for students to relax or eat, is a state-of-the-art teaching kitchen, presided over by food writer Judi Rose, whose late mother, Evelyn Rose, was widely considered the doyenne of Anglo-Jewish cookery. Around the corner is a fully equipped gym, and down the corridor there is a line of individual classrooms, each holding only one or two students, where they get the tailored attention that they need.

That word “tailored” is apt, according to Gateways founder Laurence Field, as the whole idea behind the initiative — which looks to provide an alternative to Jewish students who struggle in mainstream schools — is to offer a “bespoke” solution for each student.

Gateways began life at the London Jewish Cultural Centre (LJCC). Field, who originally trained to be a teacher, was on staff, and part of his LJCC role was to work with schools. “I found a pattern with all the schools — that there was always a cohort of young people who were on the roll, but not attending. I was told that such students were struggling, had different issues and challenges, and that the school could not address these problems properly.”

Field found that this was a common theme with every school. “It became very evident to me that there was a gap here.” At the time, there was a filmmaking studio at the LJCC, so Field wrote a proposal, and got seed money from the U.K.’s Jewish Youth Fund, to launch a 10-week filmmaking evening course for these disaffected students. He said he was warned that his prospective film students were unlikely to conform to a structure of attendance or participation. But they did, with great enthusiasm, and Field said he realized he was on to something.

“As we worked with these young people it became clear that they didn’t just want to come on a course, they wanted accreditation.” Field decided to expand his basic model, recruited a small team of staff and offered daytime courses to 15- and 16-year-olds. “We realized it wasn’t just vocational courses that were needed, but also basic mathematics and English.”

When LJCC merged with JW3, the Jewish Community Centre for London, Gateways moved, too. New programs were launched in January 2014 in cooperation with several leading Jewish schools. King Charles, paying a visit to JW3 just a few months into his reign, met Gateways students from the hair and beauty course.

In 2016, Gateways’ team received — from a foundation — a grant of £400,000 ($508,274), enabling it to do far more about meeting the demand that had been building up as more schools heard about its work.

“The focus of what we do is young people struggling with social, emotional and mental health challenges,” says Field, noting that most of the students who drop out of mainstream education do so, not because of learning disabilities, but because sometimes the pressure of a full-on school environment is too much for them.

Now celebrating a decade of activity, Gateways is planning a dinner later in the year for its earliest supporters — and, in keeping with its “can-do” approach, there will be no outside caterers. Instead, the entire kosher meal will be cooked by Judi Rose and her students.

There are now 55 students on the Gateways roll, slightly more boys than girls. Every student pays a subsidized fee, and there is also funding from local education authorities. The nonprofit also receives money from donors and trusts (it was funding from two Jewish trusts, the Wohl and Ronson Foundations, which led to Gateways’ move to northwest London), with a long-term aim of becoming more financially sustainable.

The success of Gateways within the Jewish school system in London has led to interest from elsewhere, and there are talks underway with Jewish schools in the northern city of Manchester, to see whether it would be viable to set up a Gateways school there as well. And there is interest, too, from outside the Jewish community, to see if perhaps the model would work for the general population.

Among Gateways’ success stories is Romy Gordon, 16, who has been studying at the charity for just over two years. She is now studying for academic qualifications in English and mathematics, and a vocational qualification in home cooking.

Her mother, Nadine, is a primary school teacher, but has admitted that she had nearly reached her limit when trying to help “my brave and wonderful daughter” deal with school. She says she cried when she first met Laurence Field and the Gateways team. “At that particular time in my life, I was running on pure adrenaline, trying to function and I cried a lot,” Nadine told eJP.

According to Nadine, when Romy was 14 she “was recovering from what in hindsight must have been ‘autistic burnout,’ resulting in a depressive illness and extreme stress and anxiety.”

Romy was eventually diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder — but the diagnoses came too late to get the interventions needed to help her ability to function in school. Nadine said she decided to take Romy out of school and added with some irony that people congratulated her on her “brave decision.”

Nadine quipped: “When the alternative is your child hiding in the school restrooms, sitting on the floor to avoid going into a classroom and hyperventilating about the idea of leaving the room, the decision is really made for you.”

But the family knew that Romy could not remain permanently out of the education system. What was to be done? Nadine asked around and eventually the Gordons and Gateways found each other — and Nadine believes the solution was literally life-changing. “For the first time ever, it became clear that Romy was keen to learn. She was self-motivated, she was completing homework of her own volition, she was stable, she was engaging with her learning like never before… It wasn’t a straight-line trajectory when Romy started, but that didn’t matter. Gateways didn’t give up, and neither did Romy. There was hope.”

Gateways enrolls students who have previously stopped attending mainstream school altogether. Every student must be referred, said head teacher Sasha Sharpe, “and it has to be a professional referral — it can be a school, a therapist, a psychiatrist, [Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services], the [British National Health Service’ departments that assess and treat young people with emotional, behavioral or mental health difficulties] — basically anyone other than the parent.”

Despite this requirement, Sharpe and Field said that almost every week there is a desperate phone call from a parent who does not know how to persuade their child back into education.

“When we get the calls from the parents, they are at crisis point,” Field said. “Here, the young person will find themself in a safe space where they can learn. It’s not a question of them having been dragged kicking and screaming here. They want to be here. For the first time ever, they’ve found themselves in a space where they’re not judged, but are encouraged and celebrated. They can function and get their qualifications.”

There aren’t just teachers at Gateways, but a whole “pastoral welfare department,” including therapists and psychologists. And every staff member is carefully recruited so that they must be “personable and engaging” in their ability to deal with students.

When Gateways started, it only worked with 15- and 16-year-olds, but now there are two groups of students, 14- to 18-year-olds and an older cohort ages 18-25. Some are working towards the kind of qualifications they would have done in mainstream education, while others — such as some Haredi students who have never mastered or encountered secular subjects — are tackling basic English and mathematics. Still others are studying vocational subjects such as photography or information technology, and getting qualifications as they do so.

The kitchen provides singularly tailored teaching to instruct students how to cook and shop for themselves, introducing them to store-cupboard ingredients and encouraging imaginative meals. There’s money management too, and a life skills program.

“When students come to us,” says Field, “their confidence is at rock bottom. In previous settings, they’ve been failures. They come here and for the first time they feel they can achieve, interact with peers and make friendships, get qualifications.” Sharpe says that most students stay with Gateways for between a year or two — and some go back into full-time education, even to university.

Elianna Green, who graduated last year from Gateways, is now a student at a local academy for young creatives, Elstree Screen Arts.

Speaking at a recent event for the organization’s stakeholders, Elianna said: “Due to my medical challenges, I frequently experience severe pain and fatigue. It affects my mobility, concentration and exhaustion, which caused difficulties with my school life, including anxiety about missing lessons and ultimately missing school for weeks at a time.”

But“Gateways “nourished my physical and mental health conditions,” she said. “They made me feel like a person again and always treated me with respect.”

Add EJP on Google

Add EJP on Google