new faces

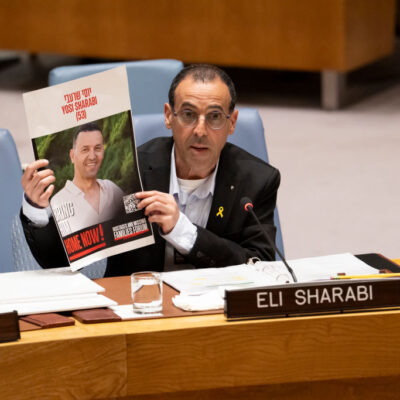

L.A.’s Holocaust museum has a new lead fundraiser: Omar Sharif Jr.

Sharif is descended from the elder Omar Sharif — an iconic Egyptian actor — as well as a grandmother who survived the Holocaust.

Courtesy of the Holocaust Museum LA

Omar Sharif Jr.

The new chief advancement officer at the Holocaust Museum LA descends from Hollywood royalty, speaks fluent Hebrew and Yiddish that he learned in day school and is co-starring in an Israeli TV series.

So it may be a surprise to discover that the new hire is Omar Sharif Jr., grandson of the elder Omar Sharif, one of the most famous Egyptian actors in history. Sharif Jr. hopes that he can draw from both sides of his lineage in his new role fundraising for the museum: He grew up with an Egyptian Muslim father — the elder Sharif’s son — and a Polish Jewish mother whose own mother survived the Holocaust.

“At the core of our mission is educating about the Holocaust, making it relevant to today and inspiring youth and young adults to tackle some of these issues that they might even see in their communities today,” Sharif, 38, told eJewishPhilanthropy. “It’s not just a history museum. It has relevance today. And it’s urgent that we address these issues, and education is the best way to do that. So I think it’s an easy and compelling case for giving.”

The Holocaust Museum LA, the oldest such museum in the United States, was founded by survivors in 1961. Last year, the museum reached almost 30,000 students and is embarking on a $45 million expansion that will fund a new 16,000-square-foot Learning Center Pavilion with special exhibits, a 200-seat theater, two classrooms, a gift shop and a café.

Thus far, Sharif told eJP, the museum has raised about 80% of the needed funds, including a $5 million gift from The Smidt Foundation. The museum hopes to be accommodating 150,000 students annually by 2030.

Sharif began the job this summer and came with fundraising chops, having recently served as lead fundraiser for the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures, guiding it through its five-year, $388 million capital campaign. He’s a best-selling author and an LGBTQ advocate who served as national spokesperson at GLAAD. In addition to English, Hebrew and Yiddish, he speaks Arabic, Spanish and French.

Sharif’s own history also informs his commitment to survivors’ stories. He lived with his maternal grandmother for several years while growing up, and from a young age, he recalls hearing his grandmother — who had survived several concentration camps, including Auschwitz — retell her Holocaust experiences, giving him nightmares as a child.

“I was always very aware,” he said. “The tattoo on her forearm was always a stark reminder. And it was always very visible and prominent in my mind… She was a smuggler in the Warsaw Ghetto. She made it through to almost the end of the Warsaw Uprising hiding in the ghetto. And she had very vivid memories of every moment.”

Sharif remembers having visited the museum with his mother about a decade ago, and especially remembered the building’s architecture, designed by architect Hagy Belzberg to give visitors the feeling of descent and ascent as they move through the exhibits.

“As you get towards the darkest parts of the of the history of the Holocaust, the building goes subterranean and darker and evokes this feeling of grief and anguish and fear,” Sharif recalled. “Then you come out the other side and light starts to filter back in, and you start to get the sense of hope again, and humanity. But I do recall being in that darkest area of the museum.” Because his grandmother had shared stories about being in the Majdanek concentration camp, including about the selection process when she was separated from her sister, Sharif said that the area memorializing Majdanek specifically “is always what breaks me the quickest.”

The messaging of the museum is “clear, easy and compelling,” Sharif said, calling it “not only relevant, but urgent” in times when hate crimes are rising both nationally and in Los Angeles county.

After his grandmother died in 2013, Sharif became even more committed to Holocaust remembrance. “Because the survivors are sadly leaving us, it’s more important than ever to sort of capture and memorialize their messages.”

His background also provides an unusually diverse level of cultural awareness. He wouldn’t characterize his upbringing as “religious,” but rather “cultural,” he said, having had a bar mitzvah during the years when his family lived in Montreal and having attended Jewish day school for a few years.

“I had these two sides of my family,” he said. “And we would gather for cultural [and] religious festivities on all sides. So whether it was Passover or the High Holidays with my mother’s side of the family, or whether it was Ramadan with my grandmother in Egypt, or [because] my grandfather was born Catholic, we would do Christmas with his mother and sister. I grew up experiencing and appreciating the different elements.”

While those influences could have been points of conflict, Sharif said he saw “so much similarity between them.” At the core of all of these festivities was family and food. And there was much more in common than there was that separated the different observances of the different religions.”

In 2012 Sharif wrote an open letter in the LGBT newspaper The Advocate coming out as both gay and half-Jewish and questioning the new Egyptian government’s commitment to basic human rights and diversity.

“I write this article despite the inherent risks associated because as we stand idle at what we hoped would be the pinnacle of Egyptian modern history, I worry that a fall from the top could be the most devastating,” he wrote, roughly a year after Arab Spring protests in Egypt led to the ouster of President Hosni Mubarak. “I write, with healthy respect for the dangers that may come, for fear that Egypt’s Arab Spring may be moving us backward, not forward. And so I hesitantly confess: I am Egyptian, I am half Jewish, and I am gay.”

His column was met with immediate condemnation, criticism, threats of violence and court cases calling for his Egyptian citizenship to be revoked.

“The letter was meant to be hopeful and optimistic and about building a newer and stronger Egypt together in the wake of a revolution, and the opportunities that lay ahead of us,” Sharif said. “I thought that might be something that everyone could rally around. In the end, that wasn’t the case.”

The letter had its upside, as well, he added, with “hundreds if not thousands” of letters from LGBTQ youth in the region, as well as letters of support from the international community. One of the first messages of support came from then-Israeli President Shimon Peres, he said, “reminding me that I always had a home in Israel.”

“I just remember how much I appreciated that offering,” he said. “One country was showing me the door and kicking me out. The other one was giving me a hand. So I always appreciated that.” Sharif is currently co-starring in an Israeli TV series known in English as “The Baker and the Beauty.”

Sharif’s famous grandfather, who was passionate about religious tolerance in Egypt among Muslims, Jews and the Coptic Christian community, is a source of inspiration to the junior Sharif.

“He just always felt that if he can share messages and create art that bridges that gap, that’s his priority,” Sharif said.

He’s channeling that respect for the messages of elders into his new job. The museum has a special exhibition called “Dimensions in Testimony,” which enables visitors to interact with a hologram of a virtual Holocaust survivor; using technology developed by the USC Shoah Foundation, survivors undergo days of detailed questions to develop a bank of answers, and are then rendered as holograms. Their answers can be triggered by questions from visitors at a later date. Each group of students that visits the museum is also matched with a survivor who can answer questions live. Sharif found the differences in the interactions to be particularly fascinating.

“They don’t want to ask questions to the survivor that might hurt them or bring back painful memories,” Sharif said. “So they tend to keep it a lot more, 100-foot level for their questioning. When they speak to the virtual survivor, they ask a lot of the tougher questions, [about] more painful memories and stuff like that. So they’re really trying to protect the survivors, and it’s really beautiful to watch.”

Sharif is also paying tribute to his background in print. His best-selling book, A Tale of Two Omars, is coming out in paperback in October, and — in the author’s own words — “touches on those multiple identities that we sort of all have and how we bridge them. So the ‘two Omars’ isn’t just my grandfather and myself, but what’s internal to me, all these internal dichotomies that I have to figure out what makes me who I am and what gives me my purpose.”

Most immediately, his purpose at the museum will be to lead the development and communications strategy for the development department as he and his team raise the rest of the money needed for the expansion, and build out from three to five staffers, in service of the museum’s mission.

“The thing I feel most passionately about is upholding the survivors’ and founders’ mission into the 21st century,” he said. “How best can we do that with new technology and with an expanded footprint? How can we make sure we never forget? But also, how do we tie it to the present, and make sure history doesn’t repeat?”

Add EJP on Google

Add EJP on Google