In first trip of its kind, Moroccan teachers explore Holocaust memory in Germany, Poland

After nine months of quiet preparation, 25 Moroccan educators stepped off a plane in Berlin on Thursday and into history. They have embarked on a journey through Auschwitz, the Warsaw Ghetto, and other Holocaust sites, which the trip organizers described as the first Arab-world teachers trained to bring this history home.

“The Journey From Hate to Hope” is a weeklong program aimed at equipping them with the tools to teach the Holocaust in Arabic through a distinctly North African lens. Organized by the Israel-based WeAreMENA regional network in partnership with Morocco’s Mimouna Association, the initiative is not only a milestone in Holocaust education — it is also a rare example of Israeli-Arab cooperation at a time of deepening regional strife.

“This is not just about memory,” Abdelhak El Kaoukabi, the director of education at Mimouna and one of the program’s key architects, told eJewishPhilanthropy. “Teaching the Holocaust in Morocco is a powerful act of cultural responsibility. It’s about moral clarity, and it’s about intercultural dialogue.”

Bridging two worlds, led by a mixed team

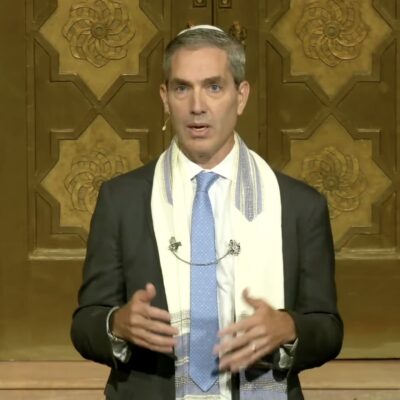

The delegation is being led by George Stevens, an American-born educator from Philadelphia who made aliyah in 2011 and now lives in Sderot. Stevens has spent the past two and a half years developing the program through WeAreMENA, which connects youth organizations across the Middle East and North Africa. His goal: to rehumanize narratives between Jews and Muslims and empower educators to teach the Holocaust not just as a European tragedy, but as a human one — with relevance to Arab history and society as well.

“There has been institutionalized ignorance around the Holocaust in much of the Arab world,” Stevens said. “Our aim was to build something serious — not just handing teachers new textbooks, but giving them deep historical grounding, personal connection and the ability to teach with meaning.”

Stevens recruited a team of Israeli and Moroccan experts, including Holocaust educators, North African historians and professional guides experienced in working with Arab and Druze groups. The mixed team — Muslim and Jewish, Israeli and Moroccan — met in advance to prepare the itinerary, translate materials and align pedagogical approaches.

“Our educational team is intentionally diverse,” said Stevens. “And while the participants are all Moroccan, the perspectives they’ll hear will reflect a range of lived experiences — including my own family’s history in the Holocaust.”

A program years in the making — and grounded in Morocco

Mimouna, the Moroccan nonprofit co-leading the initiative, has long worked to preserve Jewish heritage in the region and promote Muslim-Jewish understanding. In 2011, Mimouna organized the first-ever Holocaust conference in the Arab world. Since then, it has helped expand Holocaust education into Moroccan classrooms and participated in official events marking International Holocaust Remembrance Day.

“The vision comes from Morocco itself,” said El Kaoukabi. “His Majesty King Mohammed VI has delivered a letter stating the Holocaust is one of the darkest chapters in human history and must be taught. We’re following that vision — and showing our students that truth, empathy and courage matter.”

The teachers selected for this inaugural delegation come primarily from Essaouira, a coastal city known for its cultural openness and history of Jewish-Muslim coexistence. El Kaoukabi said the educators, many of whom teach in rural areas, volunteered for the program and spent months in online training sessions on antisemitism, North African Jewry, and Holocaust history. All the materials — from brochures to lesson plans — were developed in Arabic and tailored for Moroccan audiences.

“Nothing should be lost in translation,” El Kaoukabi emphasized.

Sensitive timing and cautious optimism

The trip, which began on Thursday, unfolds at a time of intense tension across the region. Since the war between Israel and Hamas, normalization efforts between Israel and Arab states have largely stalled. Stevens, who was evacuated from his home in Sderot after Oct. 7, described the planning as “emotionally and diplomatically complex.”

“We submitted our proposal to the Claims Conference just six days before the war began,” he said. “And while our Moroccan partners never wavered, institutionally and politically, things became harder.”

Still, the program moved forward. It received backing from the Claims Conference, the local school network in Essaouira and even the city’s mayor.

“There are no Israeli participants in the delegation,” El Kaoukabi clarified. “But the guides and educators we will meet are Israeli, and we’ve been transparent about that from day one. Our policy with the teachers is simple: no taboos. We are here to learn history, ask questions, and pass knowledge to the next generation.”

A wider vision

While “The Journey From Hate to Hope” is the first of its kind, its organizers hope it will not be the last. Tom Vizel, co-founder of the WeAreMENA network, said the goal is to eventually expand the model to educators across the MENA region.

Stevens was recently invited to present the program at the British House of Lords, where he was struck by what he heard from some of the U.K.’s leading Holocaust educators. “The heads of three major organizations came up to me afterward and said, ‘Our challenges are exactly the same,’” he recalled. “They told me, ‘In British classrooms today, when we bring up the Holocaust, students immediately ask about Gaza — and many teachers don’t know how to respond.’ It reinforced that what we’re doing isn’t just about Morocco,” he said. “It’s about giving educators the confidence, the language and the grounding to teach truthfully — even when it’s hard.”

Looking ahead

With members of the delegation on the ground in Berlin, Stevens acknowledges the challenges ahead — from navigating political tensions to addressing difficult questions that may arise during the visit. But he believes the program’s strength lies in its honesty.

“We’re not here to agree on everything,” he said. “We’re here to understand. To give history the dignity it deserves — and to give these educators the tools to carry that history forward, in their language, in their context, with their students.”

For El Kaoukabi, the goal is both clear and urgent: “If we can’t train the teachers, we can’t reach the students. And if we don’t teach the truth, we risk repeating the past.”

Add EJP on Google

Add EJP on Google