Opinion

READER RESPONDS

This just in: Let day school students teach themselves, and each other, about Israel through journalism

Shuki Taylor’s thoughtful, solutions-oriented piece about Israel education in eJewishPhilanthropy (“From ambiguity to clarity: What Israel education must confront now,” June 26) describes a problem that both frightens and inhibits educators in Jewish high schools and youth programs chutz la’aretz (outside Israel) worldwide, positing that clear boundaries as to what may and may not be said will help teachers relax about what they can teach without worrying about what they can’t. Unfortunately for all of us, the situation in Israel grows more complicated every day, so neither education nor public discourse is likely to be contained for long by a protocol of red lines to avoid. Moreover, such protocols bypass what is probably the best, most proven way for students to understand any subject — that is, investigating, discovering and wrestling with the facts on their own.

Instead of regulating what our teachers can teach, our schools should openly and officially help students investigate both history and current events in Israel for themselves. Fortunately there is another pedagogical tool that a growing minority of Jewish schools are working with already: high school journalism, which can be naturally enlisted at this critical moment and whose techniques should be adaptable to the classroom of any teacher.

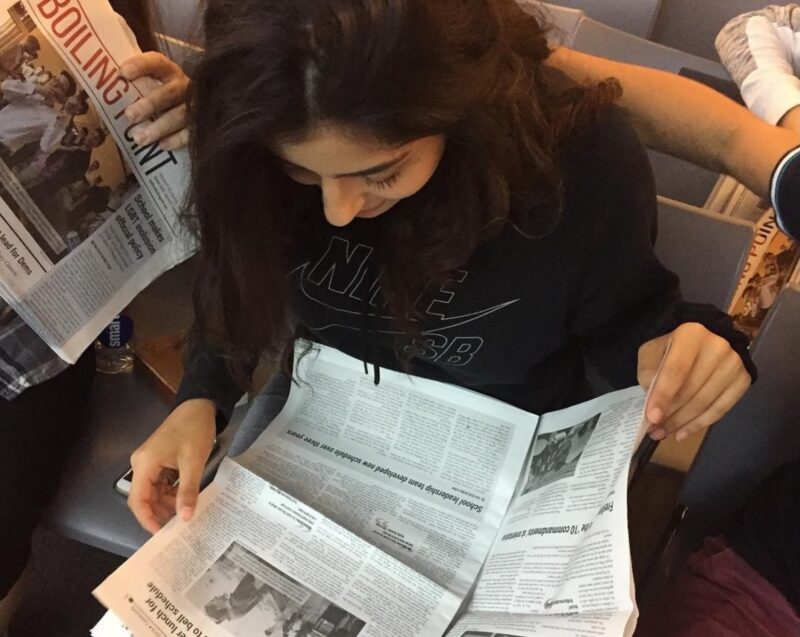

Shalhevet Boiling Point/Instagram

Students at Shalhevet High School read the latest issue of their school newspaper, The Boiling Point.

Think of it this way: Most people today, including our day school students, get their facts from other people’s opinions, which of necessity emphasize certain facts while deemphasizing or completely ignoring others. But opinions based on partial information cannot stand against facts, or even pseudo-facts, which may arrive later and without day school supervision. Letting students discover facts on their own will build deeper, more lasting knowledge, owned with more confidence and more able to adjust to new information and events throughout their lifetimes.

High school journalism teachers know how to teach the necessary skills, and in my experience their students are eager to learn and to try them out. Like the teachers who Taylor describes, these students are held back not by lack of interest, but by fear — of ridicule, censure or rebuke, especially from people they respect. Bequeathing, however inadvertently, such fear to the next generation blocks students from getting the full picture that they themselves wish to see. It also sets them up for feelings of betrayal when exposed to such information for the first time in college or beyond.

Perhaps most importantly, hiding publicly available information to any degree abrogates our duty as educators to teach students how to wrestle with complexity and how to think for themselves. The most difficult allegations levied against Israel, Israelis and Jewish religion and culture should be faced and rebutted, where possible, or faced and confronted and wrestled with where not. There’s no reason not to let young minds try to assimilate all this – because they can, and because they’re young and creative, and if our generation’s answers don’t bring peace, we will need theirs to try. In other words, it’s important to let them have at it, and to take advantage of the independent thought and imagination of which they are capable — and will continue to be if we don’t stifle it.

National high school journalism organizations like the Jewish Scholastic Press Association (JSPA) ready students and advisers to develop these very skills; in JSPA’s case, in an environment grounded firmly in Torah that aligns students’ thirst for knowledge with their spiritual identities as heirs to a particular sacred tradition. Our tradition eschews gossip but is fearless about demanding truth, justice and thoroughness, while holding leaders accountable and also being sensitive to the unique power of language. In my role as JSPA’s executive director, I helped students in several Jewish high schools use these principles to convince administrators to let them cover the 2024 presidential election, overcoming fears of being “too controversial.” Much of this benefit also reaches their friends, who are far more likely to read stories written by their peers — particularly when appearing next to stories about dress code and school sports — than local, national or international mainstream news.

“Each organization,” Taylor writes of our Jewish day schools, “should engage in a thoughtful, facilitated process — whether through surveys, coaching, or diagnostic tools — to clarify their own red lines, articulate their educational values and make those boundaries transparent to their staff.” But an opinion shaped or limited by avoiding red lines is still an opinion, and someone else’s. Teaching students how to gather information for themselves requires no meetings about red lines, but rather mostly old-fashioned, basic teaching tools, as old as the scientific method and as ennobling — and challenging — as primary sources in American history. Journalism education then goes further, by teaching them how to describe what they’ve learned in language that avoids taking a stand in the writer’s voice.

For some, withholding the writer’s voice might seem to contradict an essential mission to promote the Zionist cause. Yet here too, objective, fact-based journalism serves the greater goal. Our Jewish day schools work to inculcate a certain perspective, from which any graduate would view Israel’s existence and place in the world as politically, religiously and personally important. A reporter’s perspective starts from such a place and then reaches out as widely as possible, seeking a maximalist view and sharing as many viewpoints and as much information as it can. (Bias, on the other hand, ignores some facts in favor of others in order to support a desired conclusion.)

It’s perspective that creates the ground in which a true and honest Zionism can be planted. Just as American patriotism is not undermined by an honest accounting of, say, the Civil War, Zionism need not be weakened by exposure to its controversies or difficulties. Looking honestly at the facts of Israel’s current situation while still in school creates the possibility of incorporating them into a worldview that is honest and that develops ideas and opinions naturally. It should be the goal of any institution that cares about the long-term orientation of Jewish young adults that they recognize more than one perspective on what is happening there — in other words, that they hold a Jewish perspective that is also congruent with the facts, including facts occurring outside their own communities.

Such an orientation would surely require courage among school administrators, whose fears of upsetting parents and donors are no doubt grounded in real situations and perhaps experience. But more and more Jewish high schools are starting or strengthening student news media, and three cities have at least two Jewish high schools building programs. As the future unwinds before us, empowering students to discover and share with their communities is perhaps the best gift that today’s educators — and the parents and philanthropies who fund them — can supply.

Joelle Keene is the executive director of the Jewish Scholastic Press Association. From 2003 to 2024 she was faculty advisor to the award-winning Boiling Point at Shalhevet High School in Los Angeles.

Add EJP on Google

Add EJP on Google