Opinion

CITE YOUR SOURCES

The role of digital literacy in the fight against online antisemitism

The social media post makes a disturbing claim: Nazi crimes were nothing more than a British propaganda effort during the Second World War. A supposed memo from the Royal Archives accompanies the post, proposing “a covert disinformation campaign designed to ‘expose’ the atrocities committed by the Nazi regime.”

Both the claim and the so-called evidence are, of course, rank fictions, the kind of pseudohistory that AI now generates in seconds. And this is not an isolated case. Antisemitism today basks unabashedly in the digital limelight: from Darryl Cooper’s preposterous assertion that the Holocaust was an accident, to Candace Owens smearing Judaism as a “pedophile-centric religion,” to Nick Fuentes depicting the Oct. 7 attacks as high theater.

Creattie/Getty Images

We once relied on markers of expertise to discern fact from fiction, but today subject matter knowledge and a track record of accuracy have been displaced. In their stead, follower counts, likes and influencer status masquerade as indicators of credibility. Hate merchants perform choreographed rants and go viral. Authenticity — real or staged — is the currency on TikTok, YouTube and Instagram, the platforms where our children spend their lives (go ahead, ask them).

The good news is that a series of well-documented educational interventions can help young people — along with the rest of us — separate fact from fiction and spot antisemitic claims online. For Jewish communal funders and philanthropy more generally, an investment in digital literacy is a powerful and urgent tool for confronting the rise of online antisemitism.

Today’s teens spend upwards of eight hours a day online, with nearly half reporting they are “almost constantly” connected. Short-form videos, not traditional news sources, are their window to the world. Because these digital natives have been scrolling since diapers, one might assume they’d be wise to the wiles of online scammers, hate mongers and conspiracy peddlers. But they aren’t — and the stakes couldn’t be higher.

Online falsehoods don’t just mislead; they create the fertile ground where conspiracy theories flourish, with especially dire consequences for antisemitism. Research from Shauna M. Bowes at the University of Alabama in Huntsville and the Anti Defamation League’s Center for Antisemitism Research shows that conspiratorial thinking and antisemitism are intertwined. People who strongly believe in conspiracy theories are far more likely to embrace antisemitic tropes — often three times as many as those who reject such beliefs.

Conspiracy theories snare more victims than you might think. In the largest national study to date, Sam Wineburg’s research group at Stanford University tested 3,446 high school students’ ability to separate fact from fiction online. Students watched a grainy Facebook clip allegedly showing ballot stuffing during the 2016 Democratic primary. The video was shot in Russia, a fact established in seconds by entering a few simple keywords into a search engine, which returned sources like Snopes and the BBC that debunked the claim. But just three students in 3,000 — one-tenth of 1% — traced the video back to its source.

In a similar task, students were asked to evaluate a website purporting to provide “factual reports” on climate science. Ninety-six percent failed to recognize its ties to the fossil fuel industry, relying upon superficial cues such as the website’s professional look, its About page and the sheer volume of information. They appealed to critical thinking skills that served them in a culture of print, but falter in a medium governed by different rules. They trusted appearances, but appearances betrayed them.

Reputation and humility

To help young people become discerning digital citizens, we should start with an insight from the Mishna: the imperative to “speak every word in the name of its speaker” (Pirkei Avot 6:6). Our sages understood that every claim has a context, and that sound judgment requires pairing a claim with the person who uttered it.

Unless you already possess deep knowledge of a topic, your response to anything you see online should be to ask who created it and why. Common sense, right? But it’s striking how frequently intelligent people forget this, rushing instead to pore over information like a forensic analyst.

Professional fact-checkers, on the other hand, begin by practicing lateral reading: They leave the site or post in question and use the wider internet to assess the credibility of the original source. They understand that online, critical thinking begins not with close reading, but by first asking whether something merits thinking critically about.

Lateral reading doesn’t have to take hours; more often it’s a matter of seconds. Consider the Institute of Historical Review’s website. The group’s About page promises “peace, understanding and justice” and it aggregates stories from outlets like The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal. Yet, a quick search about the organization in a new tab reveals sources such as the Southern Poverty Law Center, the ADL and the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum identifying IHR.org as a Holocaust denial site. Google Search’s “About This Page” feature, built in part on research from the Digital Inquiry Group, automates this process with a single click. And what about that alleged British memo? Entering a few of its words into a search engine leads directly to a Ben-Gurion University professor’s warning about AI-generated fake history flooding the internet.

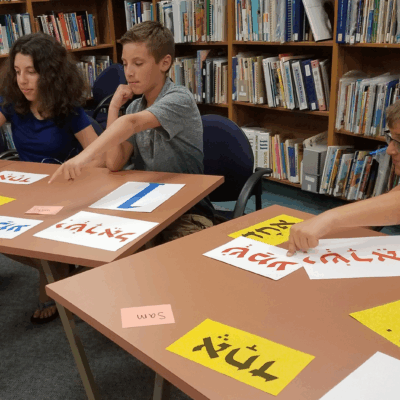

Encouragingly, we can all learn to read laterally and make better decisions. In just six hours of instruction, two hours less than teens already spend online each day, students in Lincoln, Nebraska, nearly doubled in their ability to make thoughtful choices about what to believe. We taught them “click restraint”: how to resist the impulse to click the first thing that catches their eye and instead scan the full list of search results before making a choice. We also showed them that there’s no real difference between .com and .org designations: both are “open” domains and can be registered by anyone, even neo-Nazi sites. We introduced students to “data voids,” where malicious actors seed keywords like “Elie Wiesel’s tattoo” to lure users to sites cynically designed to “just ask questions” about the Holocaust.

Ultimately, the most valuable lesson we can teach students is to resist gut checks and engage in real ones.

Such interventions are not just classroom curiosities — they are programmatic tools that philanthropy can support and scale. Disinformation corrodes civic trust while fueling resentment and hate. Funders within and beyond the Jewish world have a direct stake in ensuring young people can distinguish fact from fabrication online. Philanthropy has the flexibility to innovate quickly and to do so in ways that protect the Jewish community, safeguard other vulnerable groups and strengthen democratic life itself.

In partnership with The Diane and Guilford Glazer Foundation, the nonprofit Digital Inquiry Group, which spun out of Stanford in 2023 and became an independent 501(c)(3) in January 2024, is equipping Los Angeles-area schools with instructional materials that teach students to think critically online. This model is one that other communities can readily adapt. Rather than relying on one-off lessons squeezed between classes, these materials are woven into the regular flow of instruction — in history, civics, science and health — wherever disinformation takes root.

Even the best curriculum will not turn QAnon adherents into informed citizens. For them, the internet will always serve as a justification machine for the conspiracies they already embrace. Most students, however, are not QAnoners. They are confused, overwhelmed and looking for guidance. Eighty percent report seeing conspiracy theories in their feeds each week, yet fewer than 4-in-10 have ever been taught how to evaluate them.

Civil society cannot stop the spread of every half-baked antisemitic conspiracy theory. But we can devote time, resources and energy to equipping young people and their teachers with the skills to separate fact from online fiction and guard against conspiratorial thinking.

Why now? Because the threats are multiplying at unprecedented speed. Since Oct. 7, 2023, antisemitic conspiracy theories have surged across every major platform, amplified by AI tools that fabricate convincing forgeries with a single click. And while the coming midterm elections will certainly intensify the flood of online lies, the deeper reality is that disinformation is now a permanent feature of our digital environment. The risks are both immediate and enduring — which is precisely why philanthropy must lead with sustained commitment.

The wells of the internet overflow with lies. We have the tools today to refute them, but only if we teach people how to use them.

The choice — and responsibility — is ours.

Sam Wineburg is the emeritus Margaret Jacks Professor of Education at Stanford University and the co-founder of the Digital Inquiry Group.

Max D. Baumgarten is the director of North American operations at the Diane and Guilford Glazer Foundation in Los Angeles, where he oversees grantmaking strategies focused on strengthening Jewish life in the United States.

Add EJP on Google

Add EJP on Google