Opinion

Infrequent Observers

New research on High Holiday participation illuminates critical themes for future design

In Short

Jewish communities are constantly changing, and in the U.S. we have had a few decades of creative entrepreneurship to build on during the pandemic

Among the many ways that the pandemic profoundly changed Jewish engagement, the High Holidays of 2020 stands out as a particularly fascinating case study. It was a kind of controlled experiment; essentially no one was able to celebrate or observe the holidays in the ways they were used to, so everyone was doing something different than usual. Institutions of all kinds innovated to adapt to the restrictions, and new ways of engaging emerged and spread more broadly than could have been previously imagined.

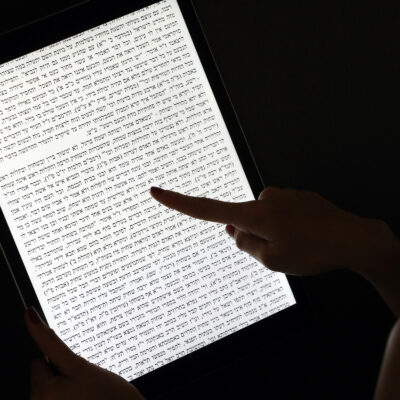

In an effort to understand the ways in which people’s engagement with the High Holidays changed during this past year, and what it might reveal about Jewish engagement more broadly, the Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Philanthropies, Jim Joseph Foundation and Aviv Foundation funded research through the Jewish Community Response and Impact Fund (JCRIF) to illuminate new patterns of participation and motivations. In the winter of 2020-2021, Benenson Strategy Group surveyed 1,414 American Jews nationwide about their experiences of the High Holidays and the ways that those experiences compared to previous years. The research explored not only what people did in 2020, but also compared it to what they had been doing before and explored what they might do in the future. The results provide important insights that have meaningful design implications not only for the upcoming High Holidays, but also for engagement efforts much more broadly.

Infrequent vs. Regular High Holiday Observers

One of the most interesting findings focuses on those who are less consistent or comprehensive in their participation in a typical year (for example, participating sporadically or only in one of the holidays). This group, Infrequent High Holidays Observers, clearly have interest in participating in the High Holidays, but choose to not participate some of the time. This year, not only did they participate at high rates, they also had markedly different patterns of participation and motivations when compared to Regular Observers, who generally participate in both Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur (and who this year largely tried to get as close as possible to “normal”). We want to highlight the findings about the Infrequent Observers as they have important implications beyond the pandemic. (A link to the full research report is available below.)

Remarkably, approximately half of the Infrequent Observers participated in High Holidays this year, when it would have been very easy to opt out. Furthermore, they were more likely than Regular Observers to report sharing their High Holidays experiences with others in their lives, more likely to be considering new ways to engage in the future, and they are looking differently at what Jewishness means to them. There are three major lessons from these positive experiences that can serve as building blocks as we plan for the future:

- Lowering Real and Perceived Barriers to Entry. A large segment of Infrequent Observers (47%) reported that “it was easy and straightforward” as a major motivation for participating this past year, more than any other single reason. By dissolving real and perceived barriers to participation, those who were previously opting out of the High Holidays some of the time leaned in this year. It behooves us to understand what people really mean by “easy and straightforward.” For example: less social anxiety or insecurity about Jewish or Hebrew knowledge, less intimidation about hours of commitment sitting in a pew, no stress about managing fidgety kids, and/or less confusion about if or how to include a partner who isn’t Jewish. Yes, cost and geography also fell away this year, but so did many other factors that have been getting in the way for many people. These lessons can be front of mind even as we design for in-person or hybrid experiences. When these real and perceived barriers fell to (almost) zero, those who are sometimes hesitant to commit their time and attention leaned in.

- Relationships were a major motivator for the Infrequent Observers, with 42% citing recommendations from friends or family members and 41% citing the desire to connect with “other people like me” as key reasons for participation. It was through relationships that Infrequent Observers found unprecedented access to high-quality experiences, a plethora of niche ways to participate that they may not have known about or had access to, and the ability to authentically celebrate with non-local family and friends. Not only did they learn about opportunities from friends and family, they were also more likely than Regular Observers to share their experiences afterward: 35% of them reported that they told someone in their life about their High Holidays experiences and 25% posted on social media about their experiences, creating a virtuous cycle to engage more of their networks in additional High Holiday programming. Those designing for future High Holidays may want to consider inviting their participants to extend invitations to their friends and family to catalyze even more of this peer-to-peer engagement.

- A Diverse Marketplace of Options. Infrequent Observers sought out a wide variety of ways to participate in the High Holidays, ranging from traditional rituals and services to mindfulness practice, volunteer or philanthropic activities, and informal celebrations with loved ones. Over 75% reported that they’d consider doing some or all of the experiences they did this year again, and 78% reported that they would consider or definitely try new ways to observe Jewish holidays in the future. These surprisingly high numbers indicate that the new levels of accessibility and exposure to creative options for engaging with the holidays supported positive, meaningful experiences that will continue to pay dividends for participants, their families and friends in the future.

Implications for Design

Because these past High Holidays required nearly everyone to reengineer their experiences, they offered a controlled experiment to test new attributes of design and accessibility. Many of the insights this data offers are not radically new. Rather, the data validates theories and design criteria that have been widely known in other fields for years, confirming that these design principles are important for Jewish leaders and educators too. These include:

- People are looking for a “just right fit,” not a “one size fits all” approach. The wide range of accessible, specific options, spread via recommendations through personal networks, helped people discover the plethora of interesting, nuanced programming and communities available across the Jewish world. People could be more confident and motivated to lean into these experiences, recommend them to others, and come back for more. There was no specific modality that was universally more attractive than any other. Depending on the individual, an ideal experience might have been a highly-produced event or a very intimate gathering, a group to meditate with, or a Rosh Hashanah cooking class (i.e. we couldn’t rely on the family brisket this year, but we could learn to make it ourselves).

- The “just right fit” is as much about the people as the content. Marketing expert Seth Godin says the bottom line of belonging is being able to say, “people like us do things like this.” Peer-to-peer recommendations and opportunities that are specific enough for a casual seeker to think “Ah! That’s where I belong!” can draw in those who are “looking for their people,” whether they slice that by life stage, creative ritual or specific areas of interest. This year, people who “found their people” actively recommended experiences and communities to others, and we saw many Infrequent Observers in turn share their experiences, too. Designing for “fit” matters.

- This year participants felt there was a diversity of valid ways to mark the holidays, beyond sitting in an hours-long service. The recent Pew data reinforces this, noting the diverse ways people engage in being Jewish (55% of those who don’t attend services often said it’s because they express their Jewishness in other ways, and of those, 77% engage through Jewish food, 74% by sharing Jewish culture or holidays with non-Jewish friends). Whereas in the past some Infrequent Observers may have perceived a binary choice (go to services or do nothing), this year they leaned into a wide range of options.

Embracing Productive Disruption

Nearly every industry in our economy has faced major disruption in the past few decades. While Encyclopedia Britannica was the gold standard of knowledge management for hundreds of years, the Wikipedia model disrupted it in the blink of an eye. Disruption is often a catalyst for a kind of systemic change that is hard to adopt voluntarily when you believe that the status quo is acceptable.

Jewish communities are constantly changing, and in the U.S. we have had a few decades of creative entrepreneurship to build on during the pandemic. But the pandemic affected everyone: it was a disruption that forced us all to design differently. In doing so, we were able to test theories and learn from the data. Now our challenge is to integrate these bold lessons into our future design, rather than returning passively to the comfortable (but not optimized) status quo. Listening empathetically and attentively to the feelings, attitudes, motivations and behaviors of Infrequent Observers will help us design effectively for greater engagement in the future.

It is hugely encouraging that half of those who haven’t been regularly participating in High Holidays are in fact seeking meaningful, well-calibrated experiences. It’s even more exciting that the vast majority of those who did participate this year want to do more, and that they are recommending their experiences to their friends. Many of these insights are also likely to apply to a subset of Regular Observers who may have the activation energy to participate every year, but for whom their experiences aren’t as positive. Let’s use this opportunity to build on this positive feedback loop.

These insights about Infrequent Observers are just one of many lessons that can be gleaned from this research effort. Curious to dive in further to the data report? The research is available at Collecting These Times: American Jewish experiences of the Pandemic.

Lisa Colton is the president of Darim Online, and a consultant working on this research and its implications. Tobin Marcus is a senior vice president at Benenson Strategy Group, which conducted the research. Felicia Herman is the director of the JCRIF Aligned Grant Program.

Add EJP on Google

Add EJP on Google