Opinion

home run philanthropy

Moneyball Judaism: ‘Winning’ an unfair game

In Short

Information and data — when used properly — can be harnessed to help an organization reach its full potential.

“Problems that are hard are usually hard because of the set of perspectives and tools that have been used to try to solve them.” -Nathan Myhrvold, former chief technology officer at Microsoft

The Jewish communities that shaped me were rich in love, but seldom rich in financial resources. I cannot recall any instance where these communities became the recipient of a significant donation of the variety that would be featured in eJewishPhilanthropy or The Jewish Week.

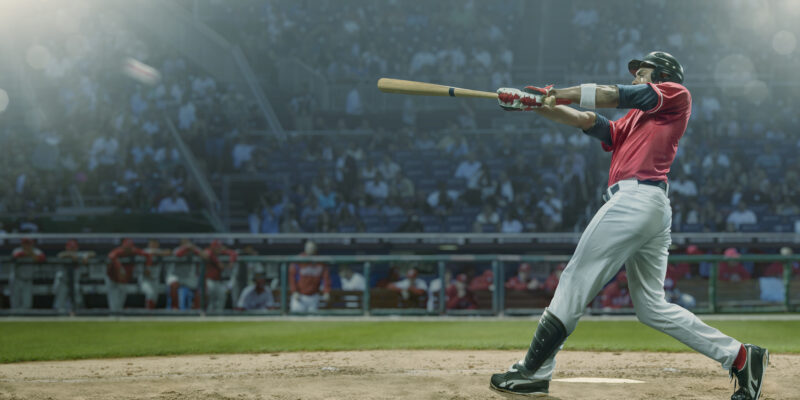

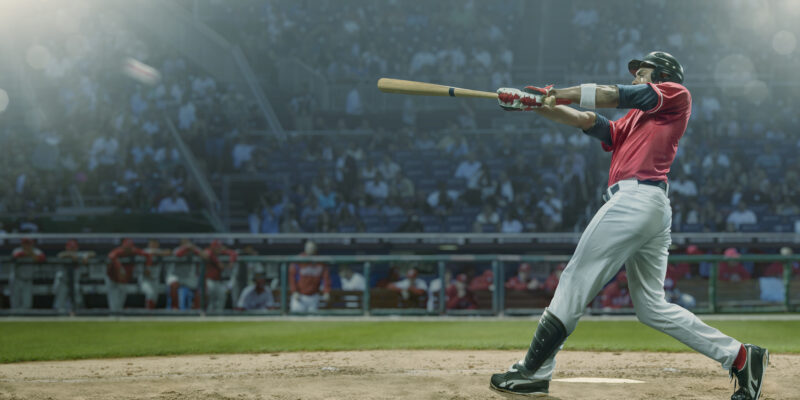

Getty Images

I always found it incredibly unfair.

While I never wavered in my belief that these communities were impactful and essential, it was frustrating to feel like other people did not see what I saw. And worse, I felt that there was no internal logic as to why certain organizations were well-funded, and others were not; wouldn’t it make more sense for communal resources to be first spent on the organizations that made the greatest impact? To me, this state of affairs felt like a bizarro version of the Matthew Effect, where the rich got richer and the poor got poorer for no discernible reason.

In such a climate, it is impossible not to become extremely jealous, even a smidge angry. Who wouldn’t be?

For years, I struggled with how to thrive as a professional in the Jewish world as it is, as opposed to the Jewish world as I would like it to be.

Then I discovered Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game.

Information As Currency

Twenty years ago, Michael Lewis published Moneyball, the story of how Billy Beane and the Oakland Athletics used data and market inefficiencies to outperform baseball teams with far larger payrolls. To this day, it’s my favorite book about leadership because it provided me with an alternative mental model to the learned helplessness that I often experienced.

Moneyball is a story about necessity. The Athletics did not have deep pockets, so they could not use their checkbook to buy effectiveness; the world was not fair. Instead, Beane, the team’s general manager from 1997-2016, won an unfair game because he realized that information is as valuable as money, if you know how to use the information to your advantage.

Most Jewish organizations are like the ones that shaped me, performing essential functions while trying to use their limited resources as best as they can. If anything, we should be impressed that the marginal impact of organizations flush with cash vs. resource-poor is so thin. At times, leaders in communities like mine probably took the same approach I did, hoping for a surprise benefactor that would leave them a massive bequest, or a devoted volunteer who won the Powerball. But false hope is not a strategy.

Instead, beating expectations comes from asking penetrating questions, searching for evidence, and finding value where others may ignore it. Questions like:

- What are the undervalued indicators of Jewish identity that organizations should focus on? For baseball nerds, the question is whether Jewish life has an equivalent of WAR (wins above replacement), PECOTA (player empirical comparison and optimization), or UZR (ultimate zone rating).

- Does any causal relationship exist between the organizations that receive the greatest amount of philanthropic funds and the organizations that produce the greatest impact?

- How can leaders focus on making better decisions by learning about heuristics, or mental biases, first identified in the work of Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman?

- What are case studies where organizations decided to make an about-face in strategy because of a clear, data-based narrative that changed their thinking?

- If people do not believe that the conventional narratives about Jewish organizational life are true, why do those narratives persist?

Today, “Moneyball” as a term is highly overused; a search of the United States Patent and Trademark Office found 38 trademarks related to the use of the word “Moneyball,” including Moneyball for Law, Moneyball for Medicine and even Moneyball for Bourbon (yes, really).

But the truth is that the Moneyball approach has become ubiquitous because it works; what was once fringe became the norm, and now every competitive baseball team uses Moneyball. And given that Moneyball principles are grounded in a rich evidence-based framework that has changed economics, politics, entertainment and philanthropy, there is no reason to think the same could not hold true for the Jewish organizational ecosystem. And yet embracing Moneyball requires that leaders run away from listening to the loudest narratives and instead seek the truth through evidence.

In September, I launched a free newsletter called “Moneyball Judaism,” an homage to the first article I wrote for eJewishPhilanthropy almost 10 years ago. Part-intellectual and part-therapeutic, the newsletter is primarily driven by my unwavering belief that there is a rich body of work that any leader can access to make their Jewish organization more effective, regardless of whether or not that organization ever becomes the recipient of tremendous financial largesse.

And in a world where countless synagogues, camps, schools, startups, Hillels, social services agencies and federations are trying to do their best with the resources they are given, choosing to look for value in unlikely places is the best pathway to beating expectations. The question becomes why so many are too afraid to embrace it.

Chasing Broken Myths

Like many graduates of the Jewish Theological Seminary who studied under Rabbi Neil Gillman z’’l, I was deeply affected when Rabbi Gillman taught me about Paul Tillich’s concept of a “broken myth.” Sometimes, facts emerge that make it impossible to believe a previously timeless religious narrative, like how evolutionary theory upends the Creation narrative in Genesis 1. And yet, Tillich argues in The Dynamics of Faith, “Those who live in an unbroken mythological world feel safe and certain. They resist, often fanatically, any attempt to introduce an element of uncertainty.”

The same can be said for Jewish organizations: some organizations feel like everything they do is blessed; some feel like everything they do is cursed. Both narratives are wrong. And while it is reasonable to worry that a debate over the authorship of the Torah could lead to a crisis of religious faith, buying into a simplistic narrative about organizational life is a self-inflicted wound.

But accepting the alternative is scary. In Moneyball, Michael Lewis writes that what made this baseball revolution controversial was that, “if gross miscalculations of a person’s value could occur on a baseball field, before a live audience of thirty thousand…what did that say about the measurement of performance in other lines of work?” In the Jewish world, how many hours of work and millions of dollars have been wasted in supporting decisions and assumptions that were flawed from the get-go, destined to fail because an organization internalized a broken myth? The answer is impossible to know, but the thought that there are cash-strapped organizations following roads to nowhere breaks my heart.

The goal of Jewish life is not to “win”; we can thrive with countless kinds of communities and organizations to succeed in what I once called the infinite game of Jewish life. But to do that, we need to accept that most organizations will not thrive merely hoping for a philanthropic windfall. Instead, we need to teach leaders how to use information as their most important currency, information that can make an incredible impact even if that organization never becomes the most attractive funding priority. And the more leaders who embrace this approach, the more healthy, thriving Jewish communities there will be.

That is a dream worth fighting for.

Rabbi Joshua Rabin is the founder of “Moneyball Judaism,” a free weekly newsletter that provides Jewish leaders with easy-to-digest explanations of trends in behavioral economics, social psychology, decision sciences and organizational development. To read more of his writings, visit www.joshuarabin.com.