FORWARD THINKING

A vision to secure Israel’s food supply

‘I think this war has made people realize that we need to return to our roots, return to the land, because without that it will be almost impossible to live here,’ Yoel Zilberman, co-founder of Hashomer Hachadash, told eJewishPhilanthropy.

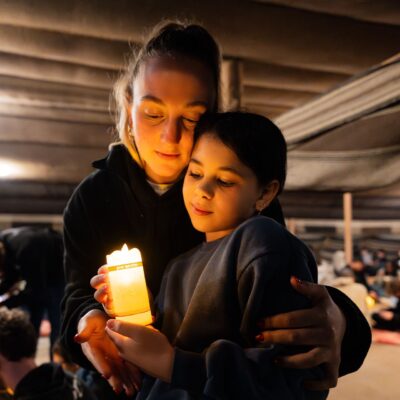

Courtesy/HaShomer HaChadash

For more than 15 years, Yoel Zilberman has been working to raise awareness to the plight of Israel’s farming industry. Hit hard over the past three decades by changes to the iconic kibbutz model and vulnerable to crime, the sector is now in further disarray following Hamas’ horrific Oct. 7 terror attacks, which destroyed multiple agricultural communities and decimated their workforces.

Now, says Zilberman, co-founder and CEO of Hashomer Hachadash, a fast-growing Zionist organization that emphasizes connection to the land of Israel, it is time for the Jewish state and world Jewry to step up and reshape this essential industry — not only as a way to support struggling farmers or help rebuild communities devastated by Hamas, but also to secure the country’s food supply for future crises.

“It became very clear after Oct. 7 that Israel was in a new phase,” Zilberman, 39, told eJP in a recent interview. “Israelis and world Jewry suddenly realized how important it is for us to have an independent food supply and how dangerous it is for us to be so dependent on imports from other countries.”

Unlike Israel’s powerful defense systems or innovative energy resources, Zilberman argues that less emphasis has been placed on agriculture and the food security it can provide, with Israel instead relying heavily on produce imported from countries such as Turkey, Jordan and Ukraine.

“I think [the current conflict] has made all of us realize that we are too dependent on countries that could suddenly stop supplying us with food,” he stated, highlighting Israel’s precarious relationships with Turkey, which has already halted imports, and Jordan, which is highly critical of Israel over its military campaign in Gaza, as well as Ukraine, which is in the midst of its own turmoil.

In Israel, Zilberman said, the Hamas attacks, which destroyed many agricultural communities in the Gaza Envelope, and the ensuing evacuations in the south and north, have brought into sharp focus the crucial role that such communities, which dot Israel’s borders, can play in strengthening the country’s security.

And, he believes, the shocks caused by Oct. 7 will afford Israelis the opportunity not only “to rebuild the security system in a new way” but also refocus Zionism with an emphasis on loving and nurturing the land.

It will require a real change in the Israeli mindset, explained Zilberman, adding, “We first need to return security to these areas and then we can rebuild the agricultural ecosystem differently with a focus on high-tech so we can generate more food and make farming more profitable in order to sustain us for the future.”

A former Israeli Navy SEAL who has been serving in the reserves since Oct. 7, he said that such changes were the only way to get “families to leave the center of the country and understand the mission to live on the borders of Israel, because this is the future of our security.”

The transition from startup nation to agri-tech innovation would also provide “solutions to a problem that is worrying the whole world,” said Zilberman, highlighting that his goal is to see goods mass produced in Israel transported throughout the whole region and beyond.

“I believe this is the next stage for Zionism,” Zilberman continued. “It is something we put aside over the past few decades because we thought it was more important to build the business sector, and while that is a very important and strong engine for Israel, I think this war has made people realize that we need to return to our roots, return to the land, because without that it will be almost impossible to live here.”

Zilberman’s love of the land, and his vision for Israel’s future was born out of his personal experience growing up the son of a farmer on Moshav Tzippori in the lower Galilee.

The self-described shepherd told eJP that as a young adult he was forced to protect his family’s property from thieves and criminals. It was during those years he realized that there was a “state epidemic” and “a deterioration in national and personal security in Israel.” Small, independent farmers were becoming increasingly vulnerable and, according to Zilberman, would not survive without “a new Zionist movement to deal with the problem.”

Drawing inspiration from the “pioneer generation,” which first settled the land of Israel, Zilberman, together with On Rifman from Kibbutz Revivim in the Negev, found Hashomer Hachadash (Hebrew for the New Guard) in 2007.

“When you talk about agriculture and love of the land, it is something that since the 1980s – since the kibbutzim stopped functioning – had completely broken down, and it became very clear to me that there was a younger generation who was never exposed to the story of our land,” Zilberman explained, pointing out that loving and developing the land of Israel was a central tenet of early Zionist ideology that also served to connect Diaspora Jews to the Jewish state.

Over the years, Hashomer Hachadash has grown to become one of the largest volunteer movements in Israel, with a quarter of a million annual volunteers learning how to renew the connection to the land of Israel through actions of “civil courage,” Zilberman described. With an array of educational programs starting with teenagers, he said the movement was working to “form alliances between all parts of our nation and society.”

It was this vast network that allowed Hashomer Hachadash to slot into place almost immediately following Oct. 7, providing farmers with critical support that allowed them to continue producing food for the country during a disruptive war.

“The structure of Hashomer as the biggest volunteer organization in Israel allowed us to be ready immediately,” Zilberman told eJP, describing how the movement quickly enlisted volunteers from Israel and abroad to help.

“It saved the livelihood of hundreds of farmers, and it saved hundreds of farms,” he continued, adding that the organization also assisted them in applying for financial support from the government and created opportunities for loans from individuals concerned about the food supply chain.

It’s an ongoing process, Zilberman said, with Hashomer Hachadash continuing to facilitate volunteering opportunities and expand its educational programs, including opening two additional agricultural boarding schools, where students spend half their day working on farms, and pushing the government to ensure that more Israelis understand the importance of agricultural communities for the country’s security.

It is part of an ecosystem that he hopes will eventually feed into border communities, including those attacked on Oct. 7, bolstering Israel’s agricultural sector, which in turn will protect its perimeter from continued threats and address the risk of food insecurity that Israel, and the whole world, is grappling with.

Add EJP on Google

Add EJP on Google