rebrand

Elluminate — formerly Jewish Women’s Foundation of New York — expands mission to focus on social entrepreneurs

Now, the organization is providing cohort support for women leading organizations, and is eyeing further expansion.

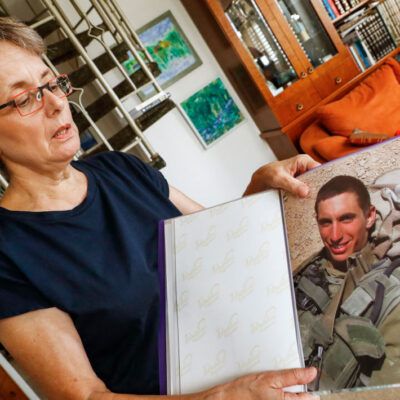

Courtesy of Elluminate.

Jewish women gather at Elluminate's conference in New York City this week.

When Lara Mendel was 15, she attended a weeklong summer camp that brought together students from different backgrounds to address prejudice and discrimination. In college, she was one of several Jewish students invited by the German government to meet with former Nazis and visit concentration camps, where many of her family members had been killed in the Holocaust. These formative experiences are the origin story of The Mosaic Project, an effort co-founded by Mendel in 2000 to prevent ignorance, prejudice and segregation by convening children from different backgrounds and using peer connections and experiences to build toward peace.

Mendel is also executive director of the organization, which has served more than 75,000 people through its various programs. But because the project wasn’t focused on programming for Jews, she told eJewishPhilanthropy, her efforts seldom qualified for Jewish philanthropic support.

Then along came the Jewish Women’s Foundation of New York — which at its annual convening yesterday revealed its new name, Elluminate (derived from “elle,” the French word for “her” or “she”), to match the organization’s expanded footprint and mission.

Mendel became part of the third cohort of The Collective, a small group of women social entrepreneurs and activists who support each other, troubleshooting challenges and serving as peer support for one another.

When it was founded in 1995, the foundation was conceived as a women’s grantmaking organization, CEO Jamie Allen Black said. Now, Elluminate is providing cohort support for women leading organizations, and is eyeing further expansion.

It hopes to launch an incubator for small organizations, and to be able to provide back-office support so that organizations don’t have to bear the cost burden of duplicative effort. Elluminate also hopes to build out an emerging leaders’ program for women to learn about organizational governance during their early stages of philanthropic development, with the aim of placing them on boards at Elluminate and in other organizations. It also aims to hold a summit every two years on emergent issues related to women’s leadership and visionary philanthropy; bringing philanthropists and organizational leaders together to discuss how funding and advocacy can be harnessed to make change.

Because cohort members come in as accomplished leaders, Elluminate’s goals include “honing their skills, finding out what they need and giving it to them, giving them a safe networking space to collaborate with other leaders,” the group’s board president, Rachel Weinstein, told eJP. “It helps one to grow and work through problems and adapt.”

Another major change from the group’s original mission is the geographical specificity of its original name: Once accurate in describing its donors as being “of New York,” the organization is now headquartered in New York but has cohort members and donors worldwide.

The organization is also receiving external funding for the first time, from the Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Philanthropies, which has given the organization $50,000 to recruit its fifth cohort.

“Through the Collective, Elluminate’s efforts to expand and democratize Jewish leadership will result in a more inclusive pipeline of dynamic women leaders that reflect the diversity and vibrancy of U.S. Jewish and Israeli communities,” Rebecca Shafron, Schusterman’s program officer for U.S. Jewish grantmaking, told eJP. “We look forward to experiencing more of the impact these talented leaders will continue to have.”

Elluminate’s core components, launched four years ago, are its nonprofit leadership cohorts (The Collective) and its small groups of philanthropists (Visionary Circles), which interact with each other in a network. There have been four Collective cohorts, with 39 members in total. Visionary Circles have about 20 members, with Elluminate board members currently occupying half those seats.

Elluminate draws on the social and group philanthropy features of giving circles and community foundations, and the deep investment in a person and her idea that characterizes startup incubators, “synthesizing their key features into something new,” Allen Black said.

For example, in Mendel’s case, Elluminate’s leadership understood that her work was steeped in Jewish values and invited her to submit an application — along with dozens of others — for support. The applications were reviewed by donors in the Visionary Circles, who asked questions, watched organizational videos and interviewed project founders until they narrowed down the list to 10.

Each cohort member receives $20,000 a year for two years in support of their work, with an additional professional development fund of $5,000 in the first year.

For Mendel, someone who has worked in diversity spaces entirely outside the Jewish professional community, being part of a completely Jewish support network was new, but “absolutely phenomenal.”

“Because I do work in a diverse community, being able to tap back into being supported and tapping back into my Jewish identity and looking at how that affects my leadership style and what I do has been really profound,” Mendel said.

Weinstein said that the cohort members had founded their organizations because of their personal experiences. Rachel Zaslow had witnessed horrible birth practices as a midwife in Uganda, and founded Mother Health International, a maternal health organization working in Uganda, Kenya, Senegal, Haiti and the U.S. Evie Litwok was formerly incarcerated, and founded Witness to Mass Incarceration. Tamar Manasseh founded MASK – Mothers and Men Against Senseless Killings, a Chicago-based anti-gun-violence organization, when a child was killed at a local bus stop.

“They just don’t want to sit on the sidelines and see an injustice happen,” Weinstein said. “They waded into that space and said, ‘We need to make change here.’”

Collective members also learn from Ruth Messinger, a longtime Jewish New York community leader and former Manhattan borough president who was an early donor to the organization and now advises, educates and facilitates the cohorts. She also participates in one of the circles, and studies with the board several times a year.

Messinger added that Elluminate invests in the leadership potential of the cohort members in a way that is “unusually comprehensive and thoughtful.”

“We ask our participants to think about leadership with a gender lens, about Jewish attitudes and values of leadership and about exercising leadership with moral courage,” Messinger said. “So those are all key perspectives.”

Weinstein said that Elluminate hopes to train philanthropists as well as nonprofit executives. She described the organization as a space for philanthropists to learn the tools that will help them to be more strategic and intentional about their giving, using a gender lens, a Jewish lens and theories of social change and impact.

“We don’t want that just to apply to somebody who can write a check with lots of zeroes on it,” Weinstein said. “We want to create intentional philanthropists no matter where they are in their financial capacity. So we welcome people in all different stages and capacities of giving to participate with us. And we think that having a diverse group of women sitting around the table helping us to choose the leaders for our collective helps us to create the best, most diverse group of leaders to be a part of our collective.”

Allen Black said that each donor circle includes up to 20 women ages 29 to 91, and represents every decade in that range. The time commitment for donors is eight sessions of 2 to 2.5 hours over the course of eight months, with a lot of reading and watching videos so they can get to know prospective cohort members and their organizations.

The organization, which has a staff of five and a board of 23, operates on an annual budget of $1.5 million; funds come from its spring gala, from an investment account and from individual donations from donors including board members and those in visionary circles. Since the organization started its grantmaking in 1997, it has spent $7 million funding 300 projects and their leaders.

While the sustaining amount for participating in a donors’ circle is $3,000, people under 40 are only expected to pay $1,500. If people want to be part of a circle but are not able to give at the expected level and are passionate and bring a unique outlook or commensurate lived experience, Allen Black said, there are ways of making it work.

“Some people give a lot more and many people give a lot less. And so we’re counting on the ‘mores’ to make up for the less in terms of budgeting,” she said.

“It’s really rare that you might be able to not be the person with the most means, but still be able to sit in a room and have a voice in terms of decision-making about who’s going to get funding and who’s going to get to be part of this unique leadership experience,” Weinstein added.

Allen Black added that this looser approach helps with Elluminate’s commitment to diversity in both the cohorts and the visionary circles, a commitment that has moved the organization forward and enabled them to support more — and different kinds of — projects and leaders.

Five years ago, there were no women of color or LGBTQ+ women in the organization or participating in its programs, and only one LGBTQ+ grantee. The grantmakers and the funded projects were only Jewish and U.S.-based, and the average donor age was 70.

Now 20% of grantees are Jewish women of color; eight grantees identify as LGBTQ+; all grantees identify as women and half are under the age of 40. Grantees now helm projects in Africa, India, Colombia, Argentina, Spain, Ukraine and also Israel. Additionally, grantmakers are not all Jewish, and there’s no minimum gift requirement to join.

Mendel — who was in New York this week for the organization’s last cohort gathering and annual convening before its name change became public — also acknowledged the importance of connecting over points of passion to make change, especially across cultural or experiential distance.

“We all need to come together,” Mendel said, adding “I think Jews need to be seen as leaders in working on initiatives; we need to be seen as winners in the fight against discrimination. We need to work side by side with everybody. And that’s for our safety as well as everybody else’s safety. Because we are all interconnected.”

Add EJP on Google

Add EJP on Google