Opinion

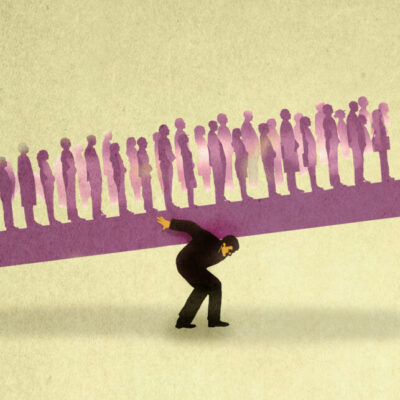

STRAIN ON THE SYSTEM

We don’t (only) have a rabbinic pipeline problem

In Short

The provocative truth Atra’s new report quietly delivers: we don’t have a rabbi problem — we have an ecosystem problem

When “From Calling to Career: Mapping the Current State and Future of Rabbinic Leadership,” Atra’s new study on the future of the rabbinate, dropped, much of the early chatter focused on one headline-grabbing statistic: that a majority (51%) of non-Orthodox rabbinical students now identify as LGBTQ+. Some communal voices have quietly wondered whether this demographic shift should itself be a cause for concern.

That framing is not neutral. It echoes the old logic that once questioned whether women could truly serve male congregants, or whether rabbis of one race or background could minister to people of another — as if shared identity were a prerequisite for spiritual wisdom.

By that logic, queer rabbis could not accompany straight Jews, which is both untrue and profoundly out of step with the reality of liberal Jewish life. Our communities are not asking for a particular percentage of straight or queer rabbis. They are yearning for extraordinary human beings who can sit with them in their pain, interpret an ancient tradition with integrity, speak honestly to what is happening in their lives and in the world and stay grounded in their own human experience.

Obsessing over whether there are “too many” LGBTQ+ rabbis is, frankly, a distraction from the far greater crisis this report surfaces: the increasingly unsustainable nature of congregational life and rabbinic work itself.

Let’s dig into that.

A story from the front lines

The Atra report listens closely to rabbis and rabbinical students across denominations, and it names the real deterrents — debt, relocation, pay, job insecurity, isolation — without blaming anyone. It also confirms what many of us feel in our bones: the work is deeply meaningful, and the path precarious.

For those of us who care about spiritual leadership — as rabbis, lay leaders, educators, funders and organizers — this kind of map is what we’ve needed. But if we read it only as addressing a “rabbi pipeline” problem, we miss the deeper invitation to rethink how leadership is formed, shared and practiced in Jewish life.

Let me make this concrete.

Years ago, a congregant I’ll call Mira (not her real name) came to see me, deeply hurt. Her husband had died. Our clergy team had been with them before and immediately after his death; but in the months that followed, she said, she felt alone. She needed more from us than we knew how to give.

Her feedback stung. The last thing any rabbi wants is to add pain in the shadow of loss. Her courage pushed our clergy team into a hard, holy conversation: What did we miss? What does real care look like not just in the week of shiva, but in the long, quiet months after?

We didn’t stop with our own reflections. We reached out to widows and widowers and asked, “What actually helped? What was missing?”

Out of those conversations came the Chesed (Loving-kindness) Companion Initiative at Leo Baeck Temple in Los Angeles. Three widows — including Mira — helped us design it. In partnership with the Bay Area Jewish Healing Center, we trained 15 lay leaders to complement clergy. Their job was simple and profound: meet monthly with those in mourning, starting about three months after a loss — exactly when the world assumes you’re “back to normal.”

The community shifted. Mourners had steady accompaniment. Lay leaders felt empowered, connected and spiritually alive. Our clergy felt less alone, held by partners in the work of comfort.

And Mira? When we first sat over lunch, she described Leo Baeck as “my husband’s community.” A few years into Chesed, she was on the temple board, taking on real leadership, and she talked about the congregation as hers.

Three years later, we launched a second Chesed cohort. Thirteen new volunteers joined; about half of the original group stayed to mentor them. The model has since been replicated at Temple Shaaray Tefila in New York City with similarly powerful results.

Success showed up in every direction: mourners and companions walking together; volunteers binding to one another in shared learning and grief; even people who declined the program saying the invitation itself mattered. It signaled: We see you. You will not have to do this alone.

That’s what ecosystem change looks like. The solution was not “work the rabbis harder.” It was to cultivate partners and leaders so that care, responsibility and spiritual labor could be shared.

There are dozens of stories like this around the country of clergy and lay leaders quietly redesigning how communities share responsibility for care and leadership. But they are still too rare; too few rabbis have the training, frameworks and support to do this work on purpose rather than improvising it on the fly.

What the report is really telling us

Read “From Calling to Career” with this lens and another pattern emerges:

- Rabbis are burning out because a small circle of professionals and lay stalwarts carry most of the weight.

- People step into deeper leadership when someone sees them, names their gifts, and invites them in.

- Communities thrive when responsibility for spiritual life and care is distributed, not rabbi-centric.

So this is not just a story about the number of rabbis. It’s a story about how we pattern power, responsibility and imagination.

At the Amen Center, we talk about “leadership-rich ecosystems” and “replacing committee culture with accountable, purpose-driven teams.” The report, in different language, describes what happens when we don’t do that: Boards become oversight bodies instead of co-creators of communities. Committees feel soul numbing instead of tapping our talents and imagination. Rabbis become the primary (or only) spiritual and civic leaders instead of the chief cultivators of many leaders.

Of course the rabbinate feels unsustainable in that system. We’re asking too few people to carry too much, inside structures never designed for transformation.

From fixing rabbis to redesigning ecosystems

One of the report’s most important findings is that the calling is alive. People still want lives of Torah, service and spiritual leadership. The problem isn’t a lack of idealism and personal fulfillment, as the report captures 97% of rabbis say their work is rewarding and meaningful.

If we take that seriously, our main question shifts from “How do we convince more people to become rabbis?” to “How do we build communities where the calling can be lived with integrity, joy and sustainability?”

That is ecosystem work.

The study finds that over half of rabbis and students trace their path to the rabbinate back to mentorship, and nearly 40% say a Jewish leader’s explicit “You should do this” was decisive. They know in their bones what it means to be seen and called forth; now the work is strengthening the muscle of seeing and calling forth others.

At the Amen Center, that means:

- Rewiring leadership culture so rabbis are surrounded by accountable, purpose-driven teams — staff and lay leaders who actually share the work.

- Training people to scout, invite, and cultivate — making that moment of “someone saw something in me” into a regular practice, not a happy accident.

- Designing roles beyond the congregation — rabbis, organizers, chaplains, educators, lay leaders — inside civic-spiritual ecosystems, not as isolated one-off jobs.

Chesed is just one small prototype. It didn’t only fill a pastoral gap. It reshaped who gets to comfort, who gets to lead, and how a community says, “We can do better. We will not leave you alone in your grief.”

A design brief for the field

If “From Calling to Career” is the diagnosis, here’s one design for a course of treatment:

- We should treat rabbinic burnout as a system design problem, not a personal failure.

- We should treat stories like Chesed as prototypes and ask, “How do we make this normal?”

- And we should treat the growth of non-congregational roles as a frontier, and ask, “What ecosystems do these leaders need around them to thrive?”

The report calls for greater coordination and shared infrastructure. The Amen Center wants to be part of that — not as the answer, but as a laboratory where congregations, seminaries, movements and civic organizations can test new models and share what works.

If we get this right, we won’t only have “enough rabbis.” We’ll have ecosystems — synagogues, networks and civic partnerships — where rabbis, lay leaders, and emerging leaders strengthen one another, deepen spiritual life and help repair the civic fabric of our communities.

That’s not just a fix to a pipeline problem. That’s the future the calling deserves.

Rabbi Benjamin Ross is the founder and executive director of the Amen Center for Civic and Spiritual Leadership. He previously served as assistant and associate rabbi at Leo Back Temple in Los Angeles and the director of adult engagement at Temple Shaaray Tefila in New York City.

Add EJP on Google

Add EJP on Google