CHANGE THE ODDS

PRECEDE works to raise awareness — and optimism — among Ashkenazi Jews predisposed to pancreatic cancer

Adobe Stock

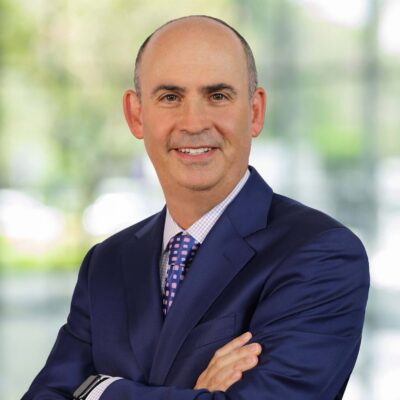

In early 2020, Jamie Brickell had a streak of good luck, beginning with what he believed to be food poisoning. He lost 20 pounds and turned jaundiced. If not for these symptoms, he’d be dead today.

Brickell was quickly diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, one of the deadliest forms of the disease. A silent killer, its symptoms typically don’t appear until after the cancer metastasizes; routine blood tests rarely catch the disease early. In Brickell’s case, the cancer blocked his bile duct, causing him to not produce enzymes to digest food. After bile backed up into his bloodstream, he was hit with jaundice. What luck.

Within a week of diagnosis, Brickell began treatment: three months of chemotherapy, a nine-hour operation to remove the cancer and, once he got his strength back, three additional months of chemotherapy. Within eight months, he was cancer-free.

“The only reason why I was able to [survive] that is because it was discovered early,” Brickell told eJewishPhilanthropy. “I actually have three friends, same age as me, all diagnosed, all died.”

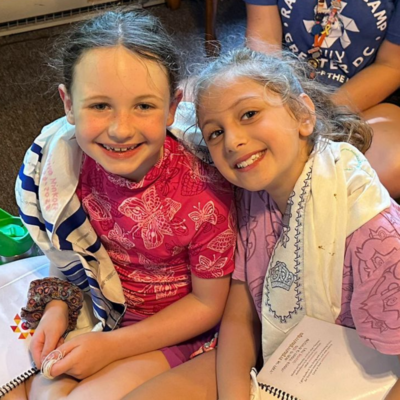

Of those three friends, two were Ashkenazi Jews.

Pancreatic cancer is the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths; only 13% of individuals diagnosed with pancreatic cancer survive five years. Research shows Ashkenazi Jews are significantly predisposed to the disease. Brickell is one of the lucky ones.

Today, Brickell, 66, an attorney, serves as president of the PRECEDE Foundation, the fundraising arm of the Pancreatic Cancer Early Detection (PRECEDE) Consortium — a group of clinicians, researchers, patients and biopharmaceutical and technology companies dedicated to research and advocacy for the early detection of pancreatic cancer, with the goal to increase the five-year survival rate to 50%. The nonprofit is reaching out to the Jewish community and hoping it listens, but it is proving to be a hard sell.

By 2030, it isexpected that pancreatic cancer will jump to being the second deadliest cancer. Historically, this type of cancer was associated with people over 60, but it is increasingly snatching people in their 30s and 40s. But at the same time, science has also developed rapidly, making it so that if pancreatic cancer is detected early, when someone has less than a two-centimeter tumor, there’s an over 80% five-year survival rate.

Still, only 10% of global funding for cancer research goes towards diagnosis, screening and monitoring for it, according to a 2023 study published in The Lancet. The PRECEDE Foundation is pushing to change this. The PRECEDE study gathers data from over 60 leading academic medical centers across the globe, including The Yale School of Medicine, McGill University, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Mayo Clinic and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, and monitors individuals with an elevated risk of developing pancreatic cancer.

The study began in 2020, with the goal of enrolling 10,000 patients, but the consortium recently expanded its goal to 20,000 participants across the world, including in Israel, with 250 participants enrolling monthly. The study is the world’s largest database of individuals at high risk for pancreatic cancer. Experts use the data to develop and evaluate early detection technologies — some of which show positive results, including early-detection blood tests and AI-based imaging.

“We could cure so many people if we just find their tumors when they’re very small,” Diane Simeone, chief scientific advisor at the PRECEDE Foundation and principal investigator and executive committee chair of the PRECEDE Consortium, told eJP. When the HIV/AIDS epidemic first hit during the early ’80s, morgues overflowed with bodies, she said, “but when you mobilize people and you educate them, and you have them working together to solve a problem, that’s how we make advances.”

For Ashkenazi Jews, Simeone recommends starting with germline testing, which identifies inherited gene mutations. Ashkenazim are predisposed to specific mutations — including ATM, BRCA1, BRCA2, CDKN2A, and PALB2 — which increase the risk to certain cancers, such as breast, ovarian, prostate and pancreatic. According to the National Cancer Institute, 5%-10% of individuals with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations develop pancreatic cancer, compared to 1.7 % of the general population. Even if someone doesn’t have a family history of pancreatic cancer, they could be predisposed, she said.

Recently, the PRECEDE Foundation reached out to individuals and synagogues in the Jewish community, hoping to provide educational information, but the community has not been overly receptive.

“Our job, as leaders in science, is to try to educate people about the best information they need to have so they can understand their cancer risk and what they can do about it,” Simeone, who was Brickell’s surgeon, said.

Brickell believes that the reason the Jewish community hasn’t been interested is that “when people hear pancreatic cancer, they automatically assume it’s a death sentence,” he said. “The genetic testing that we would talk to them about doing, people figure, ‘What’s the point?’ And we educate people that there is a point.”

If germline testing shows a person is susceptible to cancer, Simeone recommends that they get regularly screened, typically through an MRI or endoscopic ultrasound — tools which are available but have not been deployed across the general populations because they haven’t been deemed as cost-effective.

Brickell’s case — and survival — was the exception, Simeone said. “We want to make the exception become the rule.”

When the study launched, 40% of funding for The PRECEDE Consortium came from the National Cancer Institute, part of the National Institutes of Health, but today, the consortium receives less than 10% of funding from the NCI due to cuts under the Trump administration. Instead, funding comes from industry partners, such as organizations with promising early-detection tests they want studied, and individual donors, mostly making small donations. The study costs between $4 million-$5 million per year, and the foundation has raised between $2 million-$3 million per year that the study has run.

After his final chemo treatment in late 2000, Brickell wanted to give back, so he took on the role of president of the PRECEDE Foundation. “For the last three years, and that’s my way of saying, ‘Thank you.’”

Add EJP on Google

Add EJP on Google