TALENT MANAGEMENT

Post-pandemic, JCC Association refocuses on talent strategy

The association will start by hiring its first-ever chief talent officer

JCCA

Barry Finestone, CEO of the Jim Joseph Foundation. Debbie Schriber, executive director of the Union for Reform Judaism’s Northeast region for camps and youth. Lenny Silberman, CEO and founder of Lost Tribe Esports.

Despite their varied careers, these Jewish professionals all have something in common — they’ve all worked at a Jewish community center or camp.

Gali Cooks, the CEO of Leading Edge, which helps Jewish nonprofits identify, develop and support high-quality leaders, calls the movement of centers and camps a “leadership factory.” Next Tuesday, about 2,800 people who work in it will gather online for ProCon 2021, their professional development conference.

It will be the first one held since the creation of a new talent strategy created by JCC Association of North America, the umbrella organization that serves 170 member organizations — 157 centers and 13 overnight camps.

The strategy is laid out in a “Talent White Paper” that offers nine recommendations and 64 “action steps” toward the goal of shifting the culture across the movement to make professional development a priority.

“About 40% of everyone who works in the Jewish community works in a JCC,” JCC Association CEO Doron Krakow told eJewishPhilanthropy, citing Leading Edge’s estimate of 100,000 total employees in the Jewish communal workforce. “So we are working on behalf of the wider Jewish community.”

JCC Association released the paper right before the beginning of the pandemic, which forced the association to shift some of its attention away from implementation as it began to raise money for and provide crisis relief services.

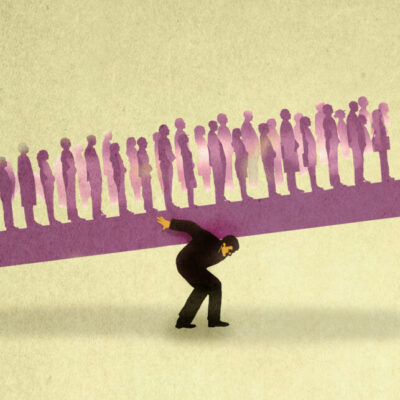

JCCs and other organizations whose business models rely on fees paid in exchange for services — like gym memberships, or childcare or classes — were some of the hardest hit by coronavirus lockdowns. At least 70% of JCCs were forced to make layoffs or reduce employee hours, as did JCC Association, said Sue Gelsey, the group’s chief program officer. Before the pandemic, 38,000 employees worked at JCC Association member organizations, according to the white paper.

Professional development is one of five areas the association has identified as ways to serve its membership, Krakow said. Others include gathering and analyzing data from across the movement to help individual organizations make decisions; fostering creative programs and replicating them; and providing relief when a local center experiences a crisis.

The talent strategy, however, has a special status.

“All the priorities are significant,” Krakow said. “We moved most quickly in the direction of talent because we think success in talent will bring success in all of these other areas as well.”

JCC Association’s emphasis reflects a broader societal shift in which those skills that can’t be automated become increasingly valuable to employers, Cooks points out, especially in organizations that provide services.

“In a service industry, the people are the asset. If you invest in them, they will appreciate” in value, she said.

JCC Association has long offered professional development opportunities, such as ProCon itself, but the white paper is the blueprint for a significant expansion.

It urges a shift in mindset about human resources, from “a vague notion that ‘people are our most important asset,’” to “a deep conviction that better talent leads to better corporate performance,” for example.

Hiring JCC Association’s first-ever chief talent officer is the first action step proposed by the paper, which also lays out the steps for creating a talent pipeline for entry-level professionals by recruiting promising high school and college students. The talent officer will also help retain and nurture early-stage, mid-level and executive-level employees.

The actualization of this vision depends on securing not just more funding, but high-profile philanthropic champions to lead the way and attract more support, Krakow said.

JCC Association wants to follow in the path of BBYO, the youth group, and Hillel International, the campus life organization, which languished until philanthropists like Edgar Bronfman saw their potential.

The association wasn’t on most philanthropists’ radar, Krakow said. He and his team are working to change that.

“We were making substantial headway when the pandemic hit, but we are in significant conversations with a number of potential cornerstone funders,” he said.

Add EJP on Google

Add EJP on Google