Opinion

Philanthropy is a key ingredient in Israel’s recipe for success on climate change

Making the greatest possible impact towards solving the growing climate crises is the primary factor that governs my philanthropy, investments and political activities.

What could possibly be more important than ensuring a livable future for generations to come?

Arid lands have long been home to 20-25% of humanity. These dry areas, constituting 35-40% of the world’s land mass, are likely to be the hardest hit by the process of desertification, which climate change is accelerating, putting the well-being and even survival of more than 2 billion people further at risk.

The challenge before us is an imposing one. Yet the country that is arguably in the best position to solve it is roughly the size of New Jersey.

Driven by the vision of its first Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion, who dreamed of making the desert bloom, as well as the cutting-edge technology of Israel’s great research centers including the academic institution that bears Ben-Gurion’s name, Israel is a multifaceted environmental innovator and disruptor — often defying the international criticism that questions its commitment to curbing climate change. From desalination to solar power to energy efficiency, the “start-up nation” punches well above its weight in designing and implementing globally replicable solutions to environmental crises, channeling the historic capacity and nature of its people to triumph in the face of adversity.

The Jewish state’s accomplishments in this space were showcased last month at the Israel Climate Change Conference, where I was among a group of speakers that included Israel’s President Isaac Herzog. Fittingly, the conference took place at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev (BGU).

Last year, my wife and I made a long-term commitment to establish Ben-Gurion University’s Goldman Sonnenfeldt School of Sustainability and Climate Change, the first of its kind in Israel.

At the same time, investor and venture capitalist John Doerr donated $1.1 billion to Stanford University to create a school focused on climate change and sustainability. That amount is more than 50 times as large as our commitment, which was made for a similar purpose. Given its size, how can our donation possibly approach the same impact as the one Doerr thankfully made to Stanford? The answer lies in the unparalleled ingenuity of Israel, which will maximize every penny of our philanthropic commitment.

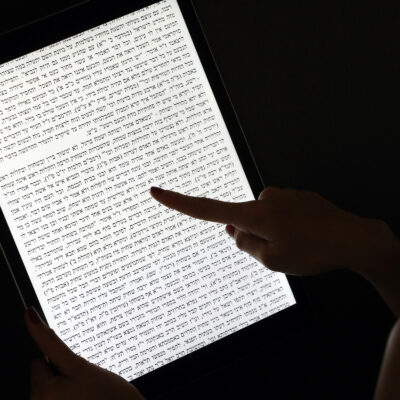

While many leading academic institutions such as Stanford focus on critically important research on climate change mitigation — efforts to reduce or prevent emissions of greenhouse gases and decarbonize the atmosphere (the root of the problem) — BGU has used its smaller but precious resources to tackle climate change through research on adaptation. For decades, our researchers have been developing leading-edge technology to help people in Israel and beyond to adapt to the harsh desert climate, such as that found in the Negev. Our desert researchers’ work is already known in many arid lands around the world. But now that desertification is accelerating, this research has global and urgent applicability.

With more than 20% of humanity now plagued by the threat or reality of desertification, what better nation is there to learn from than Israel, whose people not only know how to live in arid lands but have mastered the art of prospering in those environs?

As such, Israel is uniquely positioned to have a dramatically outsized impact on addressing the issues of climate change. However, effectively combating it requires a level of political will and international cooperation that has never been achieved before.

The Abraham Accords, Israel’s landmark normalization agreement with several Arab states, shows that seemingly unfathomable outcomes in the realm of global and governmental cooperation are not out of the question. That significant agreement, however, came to fruition because it was a collaborative effort.

Therefore, it is incumbent upon Israel’s government, as well as all governments around the world, to work together and take more concrete actions and investments if we are to cut emissions in half by 2030 to stave off the worst possibilities of climate change.

The good news is, despite the issue’s enormity, the challenge of climate change is solvable without any further new big breakthrough technologies (like fusion). This leaves ample opportunity for philanthropists, the nonprofit sector and private investors to increasingly focus their resources on addressing this existential threat, directly.

Some individuals can give philanthropically to support the effort to counter climate change. Others do not have the financial means to do so. Yet all of us, no matter where we live, possess a voice that can be heard by telling our governments that they must do everything in their power to protect future generations. And everyone can take steps in their everyday lives, even without our governments’ actions, that can dramatically scale efforts to address climate change.

The most frustrating aspect of the climate change crisis is that essentially, the science is settled; we know which policies can slow and eventually reverse climate change to help avert the growing number of environmental disasters. Perhaps the single biggest obstacle to success is the lack of political will to enact those policies.

Let’s hold our governments accountable, but let each of us look in the mirror, too, and ask if we are doing all we could be doing to address this growing threat to humanity’s very future.

Michael W. Sonnenfeldt is the founder and chairman of TIGER 21, a peer-to-peer learning network for high-net-worth first-generation wealth creators in North America and Europe; the founder of MUUS Climate Partners, a VC climate fund; and the former president of Americans for Ben-Gurion University, which supports a 21st century unifying vision for Israel by rallying around Ben-Gurion University’s work and role as an apolitical beacon of light in the Negev desert.

Add EJP on Google

Add EJP on Google