Opinion

THE FUTURE IS HERE

Jewish educators need a seat at the AI table

In early July, the American Federation of Teachers announced plans for an AI training center for educators, powered by $23 million in funding from Microsoft, OpenAI and Anthropic, three of the leading forces in the world of artificial intelligence. According to The New York Times, one of AFT President Randi Weingarten’s objectives in pursuing this initiative is “to ensure that teachers have some input on how AI tools are developed for educational use.” In other words, if you aren’t part of the conversation, you risk being irrelevant.

Unfortunately, since the AFT does not represent Jewish studies teachers employed by private schools, they will not have a seat at this particular table. So, unless we Jewish educators arrange an alternative venue, those responsible for transmitting Torah’s ancient messages to the next generation of Jewish learners will need to do so without explicit encouragement from the titans of Silicon Valley. But these companies have made their tools available to everyone, so even if we need to create our own table, stakeholders in Jewish schools owe it to the future of Jewish education to engage with the promise and the perils of artificial intelligence.

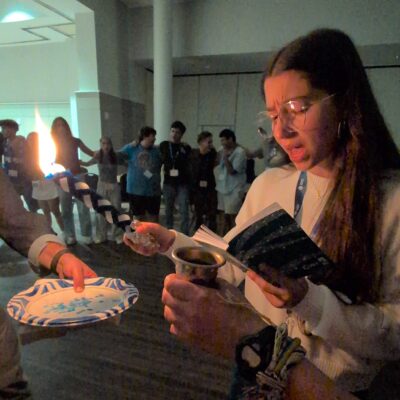

Shutthiphong Chandaeng/Getty Images

Here’s why.

The possibilities for supercharging our classrooms are real, but disruptions to education as we know it run very deep, threatening to undermine the skills and sensibilities that we as Jewish educators most want to instill in our students. “The greater the work, the greater the reward” is a famous Talmudic aphorism, but the appearance of large-language models (LLMs) such as Claude or ChatGPT may mean we have to re-think the nature of both the work and the reward. Indeed, from basic skills of decoding Jewish texts to what it means to display mastery over the content, so much is shifting.

AI’s potential for supporting students and educators alike is tremendous. Already, LLMs the dozens of tools they power hover in the cloud around us all, ready to assist both teachers and students. They can help with researching, writing, grading, creating lesson plans, creating or answering homework questions or other assessments, and breaking down language barriers. LLMs can summarize long passages, or reframe them in simpler language — and they will do it all politely, cheering your prompts and validating your feelings. A chatbot will never get tired or run out of capacity for answering students’ questions, and will continue to do so many hours after the teacher has shut down their email for the night.

The scary thing about AI is that it makes stupid tasks easy, and it also makes not-so-stupid tasks easy — or at least, easy to complete. LLMs can provide bespoke essays in seconds, but the essays were never the point. Students do not learn the thought processes that writing essays was designed to train. It probably shouldn’t take a study from Carnegie Mellon and Microsoft to demonstrate that using critical thinking faculties less frequently weakens those mental muscles.

Great educators, though, blend an understanding of their students’ worlds with their own broader perspectives, helping learners figure out how to become smarter and wiser. Knowing more than your students is not sufficient. A teacher also needs an accurate sense of what their students understand about the world, what they don’t yet grasp, and how to bridge that gap.

Educators need to invite students into the experience, and give them the muscle memory of working through problems on their own. You can’t learn to play basketball from a classroom lecture; and if AI does all the jumping for you, your legs will never get strong enough to sink a dunk, either. Sensing what learners need to be able to do and figuring out how to get them out doing it in the real world is part of what great educators do best.

Education in general and Jewish education in particular is facing an almost unprecedented challenge. But the good news is that teachers have the perfect resource on hand to help them. Never mind colleges, students in middle or high school know how to use LLMs. However, they lack the wisdom to know how best to implement it, and that’s where educators come in. When can I rely on artificial intelligence, and when is the human variety a better choice? Is using ChatGPT like using Grammarly or spell check, or is it cheating? What am I giving up when I use these tools, and what am I gaining?

Teachers tasked with bringing Torah to the TikTok generation can only be successful at sparking real learning among their students if we face these new tools head-on and together. Teachers and students alike need to be educated about AI: What it is (a powerful probability engine), what it isn’t (a mind), what it can do (make infinite suggestions) and what it cannot do (know when it’s right). They need to understand its ubiquity (Do you Google information? If so, you are already using AI), its power and the potential it holds for all of us.

The Gemara in Ta’anit encapsulates a central truth about the gift of being a teacher: “Rabbi Hanina said: I have learned much from my teachers and even more from my friends, but from my students I have learned more than from all of them.? Often, this beautiful sentiment comes laden with a kind of false humility; teachers give over wisdom and years of accrued information, and students refine our knowledge with their probing questions or provide personal exemplars that inspire us. When it comes to the AI revolution, the learning curve is steep and the students are climbing it with us, perhaps even a step ahead. All the stakeholders in Jewish education have the opportunity to leverage these new tools, together, and to take advantage of the ways that they can enhance our shared learning experience.

Sara Wolkenfeld is the chief learning officer for Sefaria.