Opinion

COUNTERCULTURAL JUDAISM

After Bondi Beach, reclaiming difference in an age of sameness

In Short

The greatest danger to Judaism today is not secularism, and it’s not even antisemitism. It is cultural absorption — the slow sandblasting of distinctiveness.

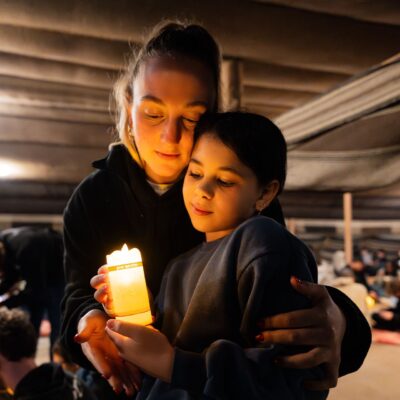

This year, we lit the first candle of Hanukkah in the shadow of tragedy. The violent attack at Bondi Beach in Sydney, Australia, which took place on the first night of the festival, was a stark reminder that Jewish distinctiveness is not only a spiritual challenge but, at times, a physical vulnerability. And yet, even in that darkness, Jews around the world kindled flames that affirmed presence, resilience and identity.

Ask almost any Jew about the miracle of Hanukkah and they will describe the oil that lasted for eight days, or the small Judean militia that defeated the Syrian-Greek army. Yet the real miracle is something most urgent today: a community that refused to disappear.

Ketut Agus Suardika/Getty Images

The Maccabees resisted cultural erasure of the ways of Torah in the face of Hellenism. Had they failed, Judaism might have faded in its cradle. This is the urgent task for Judaism today: to reclaim our countercultural vitality — not by rejecting the world but by engaging with it, with confidence in who we are.

The Maccabees ensured the preservation of a unique identity. They said “Yes” to Judaism and “No” to the aspects of Greek culture that went against Jewish values. Jews borrowed Greek words, literary forms and methods of interpretation, yet they drew a line. Out of that line emerged a Jewish instinct: the ability to face a dominant culture and respond with discernment.

This capacity to be different is embedded in the word kadosh — to be holy means to be distinct, set apart — and therein lies part of the predicament of antisemitism. Jews represent difference. We insist, for instance, that not all time is the same: Shabbat is sacred time and interrupts the seamless flow of days, a concept later adopted by Christianity, Islam and even by secular culture.

Shabbat remains the heart of Jewish distinctiveness. For some, halacha defines its boundaries. For those in non-Orthodox communities, Shabbat is often marked by making the day intentionally different: a visit with friends, a hike, a lingering conversation, perhaps even a day without phones and computers. The 2021 Pew Research Center survey found that 53% of American Jews said Shabbat was important to them. Setting Shabbat apart exerts countercultural force. It doesn’t take halachic observance to generate counterculture, but it does take intention.

Judaism also reshapes space. The table at which we eat symbolizes the ancient altar in the temples in Jerusalem. Eating becomes a sacred act, and the foods we choose (and avoid) carry identity and memory. Whether one is engaged in full kashrut observance, abstaining from particular foods or just saying a blessing or giving thanks for their meal, eating is not merely consumption.

The same can be said about communal space: we must sanctify it by making it kadosh, distinct from other spaces. Too many Jews treat the synagogue as a museum — or worse, a theater. People speak of “the audience,” as if the sanctuary were a stage. But spiritually speaking, we are in audience before God, and God is the audience for our prayers.

The greatest danger to Judaism today is not secularism, and it’s not even antisemitism. It is cultural absorption — the slow sandblasting of distinctiveness. American Judaism, in all its versions, must reclaim this countercultural stance if it hopes to flourish. The persistence and resurgence of antisemitism underscores the urgency of this task. Even as Jews gathered on Sunday to light candles celebrating resilience and continuity, lives were shattered by hatred and violence. Such moments force us to confront a difficult truth: Jewish difference has always carried risk, but relinquishing that difference has never brought safety.

Ironically, it is the struggle against antisemitism that points toward the solution. We do not fight antisemitism by diluting Jewish identity. We fight it by affirming that identity; by telling the world — including ourselves — that we have our own rhythm of time, our own sacred spaces, our own ethics of consumption, our own language of learning, our own connection to a homeland that is not just another country but our holy place.

The New Testament scholar Leander Keck once said: “I have always admired the way that the Jews have refused to allow themselves to become lost in a generalized humanity.” That refusal is our inheritance. The Maccabees fought for that refusal. Hanukkah reminds us of that refusal. American Jews must recommit to that refusal today.

That is the work we are advancing through Wisdom Without Walls, an online salon for Jewish ideas. We gather people together from all walks of Jewish life who have one thing in common: their assertion of Jewish distinctiveness. If American Judaism is to regain its countercultural vitality, let us seek out and build spaces, online and in person, that foster depth, courage and a Judaism that is confident enough to be different.

We must reclaim that confidence. We must reclaim that difference. In doing so, we will reclaim the future of American Judaism.

Sandra Lilienthal and Rabbi Jeffrey K. Salkin are the co-founders and co-directors of Wisdom Without Walls, an online salon for Jewish ideas.

Add EJP on Google

Add EJP on Google