Opinion

Try, try again

Why everyone needs a résumé of failures

In Short

Admitting your failures isn't only a recognition of your humanity but also shows that you're not afraid to be bold and take risks

“Rav Hisda teaches that ‘A good dream is not entirely fulfilled and a bad dream is not entirely fulfilled.’” (Berakhot 55a)

“If you’re so unemployable, how did you get a Wexner Fellowship?”

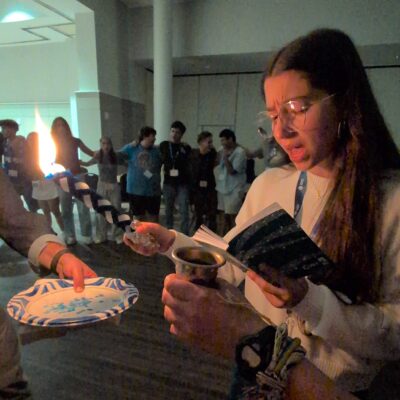

Getty Images

My entry into the Wexner Field Fellowship came during a frustrating professional period. I knew that I wanted to take my next professional step but was pessimistic bordering on fatalistic about my employment prospects. Worse, this was not a “new problem.” In rabbinical school, one of my mentors described my feelings about professional rejection as “almost pathological.” Ouch.

So tragically, when asked by my coach, who was funded by The Wexner Foundation, to explain a professional success, I struggled to conjure a semblance of an answer.

This was the first moment I thought of writing my résumé of failures.

In the Nature article, “A CV of Failures,” Dr. Melanie Stefan estimates that for every hour she spends on a successful project, she spends six hours working on projects that failed. While the extra effort does not bother her, she argues that by only posting successes on her CV, she is hiding the majority of her work. She writes:

“As scientists, we construct a narrative of success that renders our setbacks invisible both to ourselves and to others. Often, other scientists’ careers seem to be a constant, streamlined series of triumphs. Therefore, whenever we experience an individual failure, we feel alone and dejected.”

Stefan encourages colleagues to post a CV of rejections not only because it shows how much work it takes to be successful, but because it challenges a community to end the silence around failure, a rebuttal to the narrative that successful professionals must constantly present a pristine image for others to see.

Thus, during that strange and difficult professional chapter, I started keeping a résumé of failures. If this choice seems like pouring salt on a wound in a moment when one needs self-confidence, I get it. But the late legendary UCLA men’s basketball coach John Wooden teaches that “Players with fight never lose a game; they just run out of time.” The professionals I admire get up when the world knocks them down because they still have more to give, but absent specific knowledge of moments when someone one admires was knocked down, too many are left with the illusion or delusion that an unblemished professional biography is even possible.

Plus, my résumé of failures is super impressive!

The resume includes every professional rejection in my career, a veritable who’s who of the world’s most incredible Jewish organizations. The resume excludes organizations where I applied for a job but was not even interviewed; otherwise, the resume would go on for at least five pages, and I was taught that no resume should be more than two.

When I look at my résumé or show it to someone else, a few questions arise:

Was I a serious candidate for all these positions?

I hope so.

Perhaps I should be more selective in where I apply?

Possibly.

Do I sound bitter?

(Afraid to answer.)

Could I be guilty of the negativity bias, conveniently forgetting all of my professional wins?

Maybe I’m not alone, and countless others have a similar story to mine?

I have no idea.

And that is a tragedy.

Jewish leaders compete daily for jobs, fellowships, grants, donors, accolades, etc. And yet, while we are eager, often too eager, to bemoan the failures of our institutions, how often do we see leaders publicly reflect on personal failures? Ironically, in a world where “psychological safety” and “daring greatly” are ubiquitous in our professional lexicon, there remains a sizable gap between intending to speak the truth about personal failure and actually speaking about it.

Even when we do talk about failure, it’s usually an attempt to make ourselves look superior. Using terms like “failing forward” or “daring to fail” might sound vulnerable, but really it’s a way of patting ourselves on the back for trying to be innovative, some kind of weird fusion between false modesty and wild overconfidence.

Every time I mentor another professional, I first show them my résumé of failures. I want them to understand that it’s okay not to be perfect and that by sharing our stories of failure with one another, we lose nothing ourselves, but we gain everything as colleagues. Because when we cannot find affirmation from people, we are left to find affirmation in things. Feeling unrecognized is hard enough, but feeling that no one cares is far worse.

In the Talmud, Rav Hisda teaches that “A good dream is not entirely fulfilled and a bad dream is not entirely fulfilled.” In a later passage, Rabbi Berekhyah modifies Rav Hisda’s statement and says, “Even though part of a dream is fulfilled, all of it is not fulfilled.” Playing on the story of Joseph, the Torah’s ultimate dreamer, the Talmud wants us to remember that even the person who seems to achieve all of their dreams was forced to deal with disappointment along the way.

In March 2020, I delivered a version of this article at the Spring Institute of the Wexner Field Fellowship. Although it remains one of my proudest pieces of writing, I only show it to a select few. Even today, it takes courage to share all the gory details about failure, even when you know it’s the right thing to do.

And so, for you, dear reader, I have some advice:

- Don’t let a failure, a series of failures, or years of feeling like you’re a failure, keep you from dreaming.

- Keep a résumé of failures and share it with colleagues you care about and who care about you. You will feel a sense of healing, even if you don’t know why.

- Tell me your story of failure. It’s a new project I am working on. Submissions are anonymous, and the Google Form does not automatically collect email addresses.

But let’s return to the opening question…

“If you’re so unemployable, how did you get a Wexner Fellowship?”

The most important result of keeping my résumé of failures is that it finally gave me an answer for my coach. If I could do it over again, I would have said: “I am here because I don’t stop dreaming, even when I want to, with every fiber of my being.”

And you shouldn’t either. All the rest is commentary. Go and study.

Rabbi Joshua Rabin is the founder of Moneyball Judaism, a free weekly newsletter that provides Jewish leaders with easy-to-digest explanations of trends in behavioral economics, social psychology, decision sciences, and organizational development. Subscribe here and read more of Josh’s writings at www.joshuarabin.com.

This article was adapted from a piece published by WexnerLeads, the newsletter of The Wexner Foundation.