The End of the Jewish Century: 1918-2018

Why this Period Has Been Unique in the Annals of Jewish History

By Steven Windmueller, Ph.D.

As the Convention of the Central Conference of American Rabbis convenes this week to examine the state of Jewish life and the rabbinate, our Jewish leaders will have the opportunity to revisit the remarkable story of this, the Jewish Century!

Over these past one hundred years, Jews have experienced both extraordinary elements of triumph and periods of significant tragedy. Drawing on Charles Dickens’ words, “it was the best of times”; “it was the worst of times,” the Jewish century would unfold. It represented a time frame of profound contradictions and challenges to the global community. For world Jewry it can be seen as a defining moment in our long and complex historical journey.

In November of 1918, with the release of the Balfour Declaration, the dream of a Jewish homeland was affirmed. With this announcement “the Jewish century” would be born. It was the promise of national statehood that would excite a community, which had been accustomed only to periods of anti-Semitism and rejection, of anticipation and loss. Indeed, the promise of a Jewish State would be realized precisely thirty years later.

However, with the defeat of the Central Powers in 1918, the seeds were set in motion for the emergence of National Socialism and the rise of Nazism. Between 1933 and 1945, Hitler’s demonic ideas fundamentally redefined Jewish history, as the world witnessed the demise of European Jewry.

This would be however the century in which Jews emerged from being the victims of history to ultimately becoming the masters of their destiny, in turn reconstructing their story. Now, for the first time, they could define their future. Jews would not only achieve national hegemony but also gain access to Diaspora power centers, closed to them for centuries. Modernity permitted new beginnings for the Jewish world.

Based on his recent article, Andres Spokoiny offers however a different take, when he reflects on these times, “Most of our creativity and energy seems to be dedicated to form rather than content, to technology rather than substance.”

Great civilizations are marked by eight characteristics: Complex Religious Systems: Language; Literature; Governance Systems; Social Service; Public Works; and Culture and Technology. By each measure Jews have made profound contributions to the body of Western thought and knowledge, commerce and charity, science and industry, politics and culture. The extraordinary accumulation and distribution of wealth for causes parochial and secular has also uniquely defined this Jewish era.

In measuring the dominant characteristics of the Jewish Century, one might pay specific attention to the element of pride that seems to reflect how Jews have come to see themselves and their achievements in the second half of this hundred-year cycle.[1]

The quality and depth of Jewish life that has flourished during this cycle of time serves to further define who and what we have become:

- The emergence of Jewish studies as a distinctive academic discipline

- The flourishing and promotion of Jewish literature, music and the arts

- The evolution of Jewish liturgy, spirituality and worship

- The expansion of both formal and informal Jewish educational programming

- The growth of Jewish communal life and philanthropic practice

Possibly because they were denied political access during earlier historical periods, Jews have played in this age a profound role in shaping both global and national politics. Their significant presence in such transformative events as the Russian Revolution, the Spanish Civil War, America’s New Deal and this nation’s Post-War Recovery as well as its Civil Rights Movement would be testimony to their evolving and changing status.

Contrary to Andres’ reflections, this has been, in my view, a timeframe of extraordinary creativity and diversity of Jewish expression and activity. Specifically, out of the trauma and tragedy of the earlier decades of the 20th Century, Jews redefined their image and reconstructed their roles in the post-Second World War period. This symbolized a point in time when Jews would be identified as risk takers and core actors in the public arena, just as they would be seen as builders and leaders of institutions representing all segments of society. If Jews were previously identified as marginal to the public square, then in this new construct they have emerged to become the “producers” of great ideas impacting and shaping public discourse, civic action and institutional practice. The phenomenon of a minority peoples arising out of the ashes of Auschwitz to reframe not only their world but to also profoundly impact the broader culture, may best summarize this century of Jewish influence.

Indeed, during this creative Jewish season, Jews would seed two principle contributions, each reflective of different aspects of their historic pathways. The voice of the prophetic tradition, with its call for a socially just world, would be their universal message, while their struggle to achieve Zion, their historic dream of a national Jewish homeland, would serve as their particularistic contribution. The emergence of these two ideas would remain in creative tension with one another, their universalistic mandate in contention with their politics of self-interest.

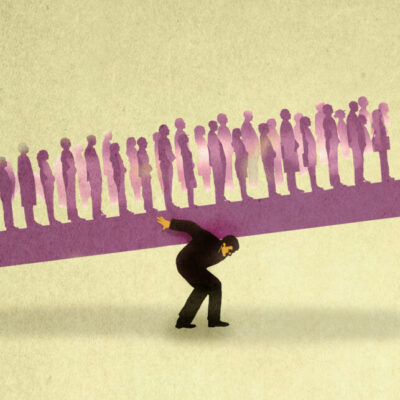

Is the century of the Jewish people coming to an end? Over time, civilizations are measured by the skill-sets and insights of its leaders, by their capacity to reinvent and grow the intellectual resources of language, culture, and religion, and by their innate ability to adapt to changing conditions, taking on threats both external and internal. Has the modern Jewish world been able to achieve the outcomes necessary to sustain and grow its brand? Among the questions before us: are we becoming a civilization bereft of inspiring, creative and thoughtful leaders and have we become a people who have so blended into Western culture, that we will no longer be able to articulate and advance a distinctive Jewish message? Is contemporary Jewish leadership subject to the same abuses of power and of entitlement that today afflict many of the core institutions within the public square? In this time frame are our leaders able to reflect on the distinctive “Jewish messages” derived from our tradition and melded into our historical journey?

At this point in time, other cultures and civilizations are now asserting their presence on the global map. The current reality may be best measured by the loss of peoplehood that so affirmed the Jewish story over these decades. Division and contentiousness have replaced the central idea of unity, as this extraordinary moment in Jewish history appears to be sun setting. Loss and discord define the current mindset of our people. Shared destiny has given way to a splintered and disjointed scenario. Coherence appears to have come undone.

As anti-Semitism rears its presence, yet again, and as Israel is challenged by its enemies and critiqued by its friends, will this next era of the Jewish saga be marked by a period of rejection and the politics of hate, as a war on the Jewish century is unleashed? Just as anti-Jewish behavior defined the formation and evolution of this century, the test here will be how those who reject us will seek to minimize our presence and marginalize our input by seeking to rewrite or dismiss this one hundred year chapter.

Yet, on the horizon one also finds the sparks of a new era of Jewish inquiry and the potential for a new century of cultural, civic, and religious creativity. Might we be witnessing another Jewish renaissance, this time not necessarily framed by great external events that defined the early 20th century but now by new generations filled with an internal vision for what the world and Judaism might look like? As some of the legacy models of the communal order recede, and as boutique instruments of Jewish expression are piercing the landscape, what might this next iteration signal? Will this new Jewish age be framed by the emergence of multiple choices of religious and communal practice, as these new actors recalibrate the Jewish experience for a different generation? Jews have always lived with an abundance of questions. As a result their unique place in human history continues to be challenged by complexity and uncertainty.

[1] www.pewforum.org/2013/10/01/jewish-american-beliefs-attitudes-culture-survey/

Steven Windmueller Ph. D. on behalf of the Wind Group, Consulting for the Jewish Future. Dr. Windmueller’s collection of articles can be found on his website: www.thewindreport.com.