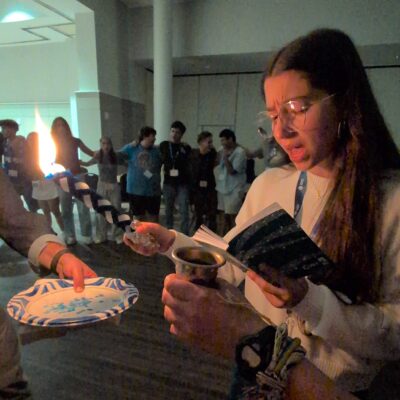

JWA’s Rising Voices Fellows Respond to Pittsburgh

Edited by Ava Berkwits

In the wake of the Pittsburgh Tree of Life synagogue shooting, the 2018-2019 JWA Rising Voices Fellows came together to reflect, respond, and call people to action. In these pieces you will find connection, sadness, outrage, courage, and compassion. You will find the strength of today’s teens who are growing up in an age of so much senseless gun violence. These pieces function not only as a reflection of personal feelings, but also as a call for collective change. We are asking for more than thoughts and prayers. We are asking you to educate yourself, to represent us when you elect legislators, to treat all humans with compassion and empathy, to stand in solidarity with targeted communities, and to use your passion, whatever it may be, to help create change – as we did in creating this piece.

I have become so desensitized to the horrific events that have happened in my sphere of awareness that news of mass-shootings is almost expected now. The hashtags, the pictures of victims, the images of vigils across the world, and the endless thoughts and prayers that play across my Instagram in the wake of horrific events feel more and more familiar each time they occur.

Often when I learn of a shooting or a disturbing event in today’s political climate, I look up the details, take a minute to process my thoughts and feel sad, and then move on. And it’s not just me who does this. When I went to school the Monday after the Tree of Life shooting, none of my friends talked about or acknowledged what had happened unless I brought it up, and even then they only agreed it was awful and moved on with the conversation.

To be honest, I was sort of astonished. I felt as if I was entering the week with the weight of the shooting still with me, and yet none of my friends seemed to share this weight. I realized that I often carried on as they did after these types of tragedies, and I felt ashamed. Ashamed because I had only cried about the shooting that explicitly targeted my community, and ashamed because I hadn’t stood in solidarity with other targeted communities in the past.

This will be a call to action for me to stand with other communities when they face tragedy, regardless of their connection to my identity. I hope in the future I will not wait for circumstances to “hit close to home” in order to feel the need to act, and that we all will treat the tragedies of any community as personal tragedies.

After

Distance, sharing blood or air-

transcended.

Those delicate threads wobble and snap between us,

this small tribe,

and I know every far-reaching blood-squeezing heartbeat, it mirrors mine.

Give me your loss, your gratitude, your fear-

I can weave it into fury, easy, though that burns like wind,

like too much room to wither.

Love takes longer, but not near as long as peace, and I’ve never made that before.

Yet

we sang through the warm air, in weathered harmony,

oseh shalom bimromav, hu yaaseh shalom aleinu…

I could see the bride’s homecoming, glowing like something to wait up for,

like something more promising than hope, like oneness,

…v’al kol, Yisrael, v’imru. Amen.

I dare not hide my tears again.

The Minyan That We All Belong To:

1.4 percent of people in the United States are Jewish. That means that from a group of 1,000 randomly selected Americans, fourteen of them are Jewish. Fourteen out of a thousand doesn’t sound like that many, but fourteen is enough, because fourteen Jews can make a minyan.

And when there are 986 other people around you that aren’t Jewish, that minyan becomes a safe haven. A place where you find connections. Where you find old matzah-ball-soup recipes. Where you find old prayers with new tunes. Where you find old women that were once young girls watching the Holocaust from across the sea. Fourteen people to build your life around; to build the identity: Jewish American. When one of those fourteen is gone, it is more than just missing a member of the minyan. It is a crack in the world you know.

When eleven people are shot down in their synagogue on a Saturday morning it is a chasm.

I have been lucky enough to spend my entire life engulfed by a thriving Jewish community with a rich culture. I have never lived in a town without a shul. I never went to a school without another Jew. But I know that we are a drop in an ocean. I know how rare it is to find another Jewish American. When I meet someone new that is Jewish, they are not a stranger. I play Jewish Geography with them or talk about the best types of challah and it is as if we have known each other our whole lives. We grew up in the same house, the same school, the same synagogue, the same minyan.

I never met Rose Mallinger, Joyce Fienberg, Richard Gottfrie, Jerry Robinowitz, Cecil Rosenthal, David Rosenthal, Bernice Simon, Sylvan Simon, Daniel Stein, Melvin Wax, or Irving Younger, but they were all a part of my minyan. I will miss them just the same.

Lila Zinner

When I was 12, I spent a year researching and advocating for refugees through the organization CARE as part of my Jewish Day School’s 7th grade tzedakah project. In middle school this project was my passion and pride. It opened my eyes to what it means to be a global citizen and to the Jewish values that necessitate us to lift up the most vulnerable. In my 7th grade Jewish studies class I learned the Jewish value: “do not stand idly by the blood of your neighbor.” I was taught that it’s Jewish to see every human as your neighbor, from your fellow congregant in synagogue to a refugee across the world.

This value is the exact reason why 11 people were killed in the Tree of Life Synagogue on Saturday, October 27th. Robert Bowers terrorized Tree of Life explicitly because of their affiliations with HIAS. Eleven people were murdered not just for being Jewish, but because so many Jews today refuse to buy into the rhetoric and policies of hate and marginalization. We are not simply being persecuted for the core identifier of our faith; we are sought out because so many Jews are actively trying to make the world a less fucked up place. Because we have refused to stand idly by the blood of our neighbors.

I think that Jews especially feel a commitment to availing the refugee crisis because over and over again we have been refugees ourselves. Refugees from Egypt in the Torah. Refugees from Spain in the late 1400s and early 1500s. Refugees from Europe in the 1930s and 40s.

Unlike what President Trump wants us to believe, we should not need a bigger, stronger gun to protect ourselves in a country where freedom of religion is literally our founding principle. The ability to kill people at will is not endowed by that Constitution either. As Americans, we have to call BS. As Jews, we have to call BS. As the descendants of refugees, and as living human beings with any moral sense, we have to call BS.

We cannot stand idly by the blood of our neighbors. Not our neighbors in Squirrel Hill Pennsylvania, or a church in Charleston, or a bar in Thousand Oaks, California. Not our neighbors walking in caravans, or our neighbors dying of starvation in Yemen or perishing in refugee camps in Greece or Turkey or even Jenin. Rallying after this tragedy does not just mean standing up for our fellow Jews. It means continuing to live Jewishly, denouncing hate in all its forms.

It was April 13, 2014. I was in 5th grade and living in Arizona. I was coming out of a gymnastics competition and I was walking towards my mom. I ask if we can go to Chipotle and she nods. We start walking to the car and my mom checks her phone; all of a sudden she stops walking and becomes pale. I ask her “what’s wrong,” and she responds that something happened at the JCC in Kansas City (the city where I was born and now live). I have no clue what that could mean besides that it wasn’t good. We get to the car and my mom tells me what happened: there was a shooting at the JCC. She tells me to start google-ing as much information as I can while she frantically texts our friends to make sure they are safe. We learn that our friends are safe, but that three people were killed by a member of the KKK.

Now, four years later, I live in Kansas City again and I go to school in the building were the shooting happened. Every morning when I walk into the lobby of the JCC I see armed security guards, and when I go into any classroom the first thing I see is a SafeDefend box. Many of my classmates were in the building that day; where the little kids eat lunch is where some hid. When we practiced throwing foam balls at our principal last year as part of an active shooter preparedness exercise, it wasn’t a game or a joke – it was reality. You think it won’t happen to you or your community until it does. I don’t know what to say about what happened in Pittsburgh besides that it is terrible and should never have happened. But I will keep going to a Jewish Day School and to synagogue and when the time comes I will raise my children Jewish. I could talk about gun control or how our current political climate is a breeding ground for anti-semitism but I won’t. If there is one thing that I have learned from all of these tragedies, it’s that we can’t give up our identities and we can’t stop celebrating who we are.

A Salt Water Song

Soon after learning to sing

Jewish children learn to form song with salt water in their mouths

We find rhythm within tears

Legs join in the horah, treading against poisoned waters.

Some days the sea is heavier

It claims a person to hatred, and blue turns to maroon

The water within our bodies turns heavy too

We perform mouth to mouth resuscitation to our community

Kaddish, Mi’sheberach, Shemah

This culmination of oxygen and rhythm must be what Hannah meant when she spoke of rushing waters.

Yesterday in Pittsburgh, a man tried to silence us

He must not have realized that this community’s collective lungs are immune to erosion.

We’ve been singing through bullet salted waters for thousands of years

And I will teach my children to sing even louder.

Every Wednesday, I attend an after-school Hebrew High program. My last class is “Jewish Philosophy” taught by an Orthodox Rabbi from the local Chabad. Although we may not always see eye to eye, the Rabbi allows us to debate him on anything, from the mundane to the philosophical. “Today we are tackling a very broad question,” he declared as he began our class last week. “Why do bad things happen to good people?” We shifted uncomfortably in our seats, not knowing how to respond. The question was pertinent and piercing in light of the recent tragedy. When 11 compassionate, lively, pious, innocent Jews are gunned down by an anti-semite with an assault rifle, it seems impossible to believe that the world is fair and just. To answer his own question, the Rabbi began sharing story after story from the Talmud. All involving devout men with long names and strong morals, the tales he told centered around a phrase: “everything happens for a reason.” At first, I scoffed at his maxim. Natural disasters, genocides, human rights violations, acts of senseless violence; what purpose do they serve? I was confused and irritated by his seemingly simple justification, and I tried to communicate my frustration to him. In response, he repeated himself: “everything happens for a reason.” A man armed with a military-style weapon walks into a temple, and I was supposed to find a silver lining? I remained skeptical about the Rabbi’s suggestion for the next few days, my thoughts clouded by resentment and dejection. Piece by piece, however, small embers of hope began to break down my mental barrier. It is true that since the Pittsburgh shooting more light has been shed on the rise of anti-semitism in America. And as yet another mass shooting has rocked the nation, the gun control conversation is more salient than ever. Although I still don’t know if I’m completely sold on the Rabbi’s catch-all phrase, the resounding support from the Jewish and non-Jewish communities alike in the wake of Pittsburgh has shown the potential power that can result from even the most devastating events. Instead of leaving this tragedy as yet another statistic, let’s work together in encouraging the passage of gun control legislation. Let’s take Pittsburgh as our call to action, a final Tekiah on the importance of protecting innocent lives.

The Rising Voices Fellowship, a program of the Jewish Women’s Archive, is a thought leadership program for female-identified Jewish teens who are passionate about writing, Judaism, feminism, and social justice.

First published on Jewish Women, Amplified; reprinted with permission.

Add EJP on Google

Add EJP on Google