A New, More Literal Meaning for ‘Securing the Jewish Future’

By Jay Tcath

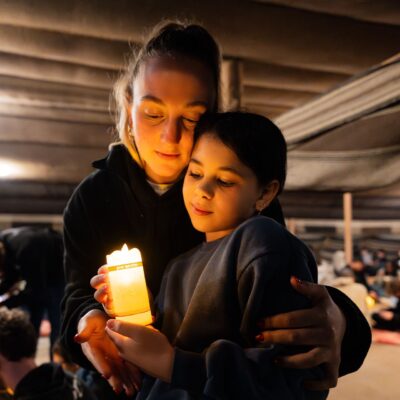

We endure this moment…

Photo by Chris Hondros/Getty Images

…to enjoy many of these:

The 1990 North American Jewish Population Study reset the Jewish communal agenda. While not exactly blindsided, the greater – than – assumed findings of diminished Jewish identity and traditional behaviors alarmed community leaders. “Continuity” became not just a buzzword but a funding and planning priority. For many, it became a new Jewish philanthropic north star.

Massive amounts of Jewish philanthropy, especially by Jewish Federations and private Jewish foundations, were both redirected from other, earlier priorities and new investments made in efforts often described as “securing the Jewish future.”

Across the United States and Canada that has meant supporting Birthright and even earlier youth trips to Israel, Jewish preschool and summer camp vouchers, innovative Jewish Day School funding initiatives, free Jewish books and music tapes for young children, teen volunteerism, synagogue and unaffiliated youth groups, young adult programming, Moishe Houses, young family playgroups, tens of millions of additional dollars for hundreds of Hilllels, and more. And an entire new eco-system of creative, impactful Jewish nonprofits emerged addressing the continuity/securing the Jewish future challenge.

Three decades after the 1990 study sparked the “continuity” wake-up call and amidst the more recent wake-up calls of deadly synagogue and other attacks, we must redefine what it means to “secure the Jewish future.” It must now take on an additional, urgent, more literal mandate: Jewish institutional security.

Yes, of course the community must still invest ever more in the “continuity” agenda and do so ever more creatively. But in a very literal sense, unless we can physically secure the facilities where the Jewish future is incubated – camps, schools, synagogues, agencies, Hillels, and JCCs – that Jewish future will itself be insecure.

Thirty years ago, we realized that only new approaches infused with significant investments would change the trajectory of the Jewish future. Today we realize that while both new programs and enhanced security are necessary, neither by itself is sufficient.

Just as there is a checklist for best practices in the “continuity” sector of “securing the Jewish future,” so too are there critical considerations and best communal practices in the institutional security sector:

- There is no one-size-fits-all security system for each Jewish facility. Security at a headquarters building used mostly by staff and regular volunteers should be different than security at a facility serving either dozens and dozens of counseling patients or a facility serving preschoolers.

- It is an imprecise line between our facilities looking like armed fortresses prepared for an imminent attack and retaining the feel and reality of open, welcoming, safe spaces.

- Funders should insist that Jewish facilities seeking support for new security gadgets actually first conduct security audits followed by developing security plans and training programs. And that distribution of multi-year grants be premised on those being taken and sustained. (A few years ago a vandal damaged a local synagogue, but its unplugged security camera failed – in both senses of the term – to capture the perpetrator.)

- Ideally funders should leverage their financial support by providing matching grants to Jewish facilities. However, not all facilities enjoy the same cash flow and thus able to access their share of a matching grant. Yet, of course, all Jews are entitled to security, not just those walking into facilities with strong balance sheets. Jewish security is not an arena to accept inequalities.

- Jewish security, like so many other issues, is not just a local, but a national challenge. Jews in small (often “remote” and under-resourced Jewish communities) face the same threats as their brothers and sisters in New York, Toronto and Miami. Think Poway, CA. Just as we don’t accept small town, “remote” campuses to have sub-par Hillels (think Champaign, Illinois, Madison, Wisconsin, Gainesville, Florida, Bloomington, Indiana, etc.), Jews in Peoria, Plano and Portsmouth are owed security and the resources to achieve it.

- Funders should insist that Jewish groups are also aggressively seeking public support for their security equipment purchases from the US Department of Homeland Security’s Nonprofit Security Grant Program as well as state, county and local sources.

- Especially for the smaller, minimally staffed Jewish groups seeking government security grants, funders positioned to do so should actively provide notification of funding deadlines, application guidance, and step-by-step technical assistance throughout the burdensome process.

- All Jewish facilities should leverage the expertise and willingness to help offered by their local Federation and the Secure Community Network (SCN), an initiative of Jewish Federations and the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations, as well as local law enforcement agencies. Security is not a solo endeavor. We are all truly better together.

- It should go without saying that any and all security systems, technologies, plans and trainings should strive to meet the standard of universal design: that people of all abilities understand, see, hear or otherwise are alerted to a danger and can physically find their way to safety.

All the security funding, all the security training and equipment, and all the security relationships are simply a means; a means to help sustain and strengthen Jewish life.

Together, with an eye towards security but our hearts focused on Jewish life, we will secure the Jewish future.

Jay Tcath is Executive Vice President of the Jewish United Fund/Jewish Federation of Metropolitan Chicago. His responsibilities include oversight of the Federation’s Security Department.

Add EJP on Google

Add EJP on Google