A Global Center for Jewish Education

By Mickey Katzburg

As we enter the winter of a school year characterized by uncertainty, the time is ripe to reimagine the structure of Jewish education in light of urgent challenges. Having worked with teachers at hundreds of Jewish schools in 15 countries over the last decade, the questions that I hear most often are- how can we create an educational experience that is deeply meaningful and relevant to our students? How can we transform students from passive consumers to active learners?

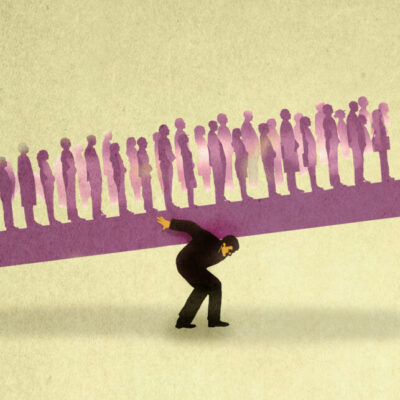

Providing answers to these questions on a global scale requires a paradigm shift in our approach to Jewish education. We must move from a model based on individual atomized institutions, to one based on the power of a world-wide educational community – “The Power of We.” In order to facilitate such a shift, we should establish an independent global center for Jewish pedagogy, focused on empowering educators, enhancing the quality of Judaic studies, and assisting school leaders in meeting budgetary challenges.

In the 2019 Israeli Government Budget, the Education Ministry received the highest budget of any governmental body – 4 billion NIS more than the Defense Ministry. The centralized structure of education in Israel allows for efficient investment in areas such as the creation of curriculum and professional development. It also allows for measurement and evaluation according to shared standards.

In contrast, in Jewish communities around the world, where each school operates as an isolated economic unit, the expenses involved in developing curriculum and training teachers are much greater. At the same time, objective and transparent measurement and evaluation are much more difficult.

The solution is a global center for Jewish education. To be clear, we are not proposing the creation of a large bureaucratic body with authority over educational institutions. Rather, we believe that what is needed is a central hub – like those that operate in the technology sector – that is smart, flexible and creative.

Such a hub can create a paradigm shift in Jewish education by focusing on what the biologist Stuart Kauffman described as the “adjacent possible.” In this model, adapted to policy planning, successful initiatives are developed by imagining how to expand small or older projects into new paradigms and markets. Birthright Israel is a prime example of this idea in practice. The short-term Israel program, which has been around since Israel was founded, was “re-imagined” into the game changer that is Birthright. Formal Jewish education needs a Birthright-like initiative of its own.

One of the most important goals of such a global center or hub must be to empower Jewish educators, who are the core change agents of the educational ecosystem. I am constantly inspired by the dedication and passion of Jewish educators. At the same time, despite their dedication, these teachers often do not have the opportunity to acquire the advanced pedagogical skills necessary to ensure that students remain fully engaged in the learning process.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the need to invest in teachers was becoming ever more apparent, due to the demand for differentiated instruction, parents’ expectations that Judaic courses be on the same high level as secular courses, and the need to convince skeptical students of the importance of Hebrew studies.

COVID-19 has further highlighted the centrality of the teacher, and the gap between those with superior pedagogical skills and those without. In routine times, when teachers could rely on presenting purchased lesson plans in a frontal classroom, development of advanced capabilities could sometimes be overlooked. Now, however, such capabilities are absolutely critical. No slick technology or lesson plan can maintain the student’s connection to the educational community in the distance learning era. Only the teacher has this ability.

The urgent need to empower teachers goes far beyond tips how to best structure lessons online. It includes developing key capacities such as utilizing dialectic and dialogical pedagogy, facilitating student-driven learning, and making Hebrew studies relevant to students’ daily lives.

Such professional development cannot be a one-time event. New teachers, and those tasked with introducing new methods, must be offered ongoing guidance. Our busy teachers need and deserve a support system available 24 hours a day to serve properly a global need.

A global hub for Jewish education must be equally dedicated to assisting schools in addressing their budgetary pressures, not at the expense of educational excellence, but rather by enhancing such excellence. This can be done in several ways.

For example, one of the significant expenses that schools face is the cost of teaching materials and tools. New Jewish and Hebrew studies curriculums often require the purchase of expensive proprietary technological platforms. However, today, platforms such as Microsoft Teams and Google Classroom, if used effectively, can replace these proprietary platforms while providing additional benefits.

The next step then is to train teachers to become proficient in creating their own curricular materials, to be shared via platforms such as those offered by Microsoft and Google. When done properly, such teacher-designed lessons can be not only more cost-effective, but more compelling.

Of course, there will likely always be a need for schools to purchase certain educational resources. From both an educational and an economic perspective, it is imperative that such materials be carefully selected in accordance with each school’s particular needs. A key role of an independent and objective center should be to assist schools in choosing from among the vast array of options available. At the same time, by connecting schools with similar profiles, such a global center will enable schools to save costs by leveraging their purchasing power.

Finally, given the reality that parents are increasingly questioning whether investing in Jewish studies is justified, school leaders will need to become skilled at both measurement and marketing.

On the one hand, they will need to integrate professional measurement and evaluation tools in order to provide transparency, prove impact and improve standards. On the other, they will need to appeal not only to rational calculations of utility, but to the deepest values and aspirations of parents and donors. Few school leaders are experienced in such measurement and marketing techniques. A global education center must provide training in these fields.

The World Center for Jewish Education, which I direct, is establishing just such a global hub. By utilizing “The Power of We,” we can create a meaningful educational experience which impacts students far beyond the school’s walls. We invite all Jewish educators, schools and organizations to join us as we work to ensure a thriving future for Jewish education.

Mickey Katzburg is the Director of the nonprofit World Center for Jewish Education, and an educational innovator with more than 20 years of experience in formal and informal education.