SURVEY SAYS

‘Identity crises’ grip U.S. Jews, the field of Israel studies, Jewish People Policy Institute fellows find

JPPI presents the two studies in a webinar on Sunday

GETTY IMAGES

Illustrative.

Young American Jews and the field of Israel studies are facing dual “identity crises”: That’s the key takeaway from two recent studies by the Jewish People Policy Institute think tank, whose findings were presented in a webinar this week.

“The main focus was more on what people are feeling,” Shlomo Fisher, a JPPI researcher and one of the two authors of the former study, said at the event on Sunday evening. “The ADL records how many swastikas are drawn on synagogues in a year, and that’s very important. We thought we wanted to concentrate on the inner experiences of American Jews, and especially of young people, and especially in connection with university campuses. And what we discovered was that there was — this is a sort of hackneyed phrase — something of a crisis in identity, or at least an issue, a dilemma of identity among these people.”

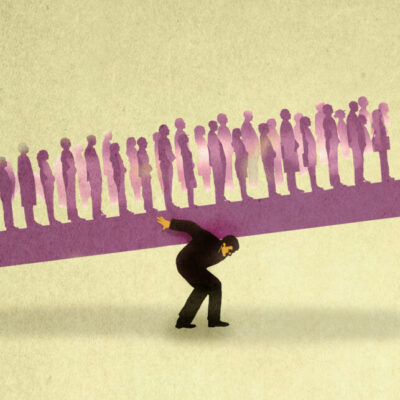

The first study found that this centered around the tensions between the respondents’ commitments to Israel and the Jewish People, which are seemingly putting them at odds with their fellow progressives, who reject American Jews’ core understanding of their place in the world.

“I view myself as a persecuted minority who has the moral authority to critique and to promote social justice concerns,” Fisher said, relating the views of the respondents. “And I’m being told that I’m part of a privileged oppressor class that is the very paradigm of colonialism and genocide. So my own self-definition is being contradicted by the outside world, by the other. That’s unprecedented. That’s very unusual.”

The study, which was conducted by Fisher and fellow JPPI researcher Rachel Fish, involved in-depth interviews with 106 participants, 58% of whom were under 35. The respondents were also more involved in the Jewish community than average, Fisher and Fish noted. The interviews, which were conducted in groups of five or six, were conducted over the course of 13 sessions.

Much of this is tied to the rising anti-Israel activism and antisemitism at American universities and colleges, whose influence, the report’s authors said, extends far beyond the campus borders.

“We know that antisemitism doesn’t exist only within the ivory towers,” Fish said.”However, we do understand that the world of ideas deeply matters, and what happens in those ivory towers impacts not only the time that students spend in the campus community, but extends well beyond into social justice movements, politics, media consumption, and the way in which our culture is developing.”

Yossi Klein Halevi, a fellow at the Shalom Hartman Institute, who spoke at the event, noted that the rise in campus antisemitism is particularly shocking to American Jews, who have long viewed higher education as a refuge. “The universities were the portal for many American Jews into the American dream,” he said.

Halevi tied the issues on American campuses to what he described as the weaponization of the Holocaust against the Jewish People by universalizing it and stripping it of the uniqueness of antisemitism.

“The Holocaust has now become one of the great weapons against Israel and against the Diaspora,” Halevi said. “And the irony here is that this generation… was raised with Holocaust education, went on field trips to the Holocaust Museum in Washington. And so the question is, what went wrong? How did the Holocaust go from being an educational tool that was supposed to protect the Jewish People to itself being one of the principal threats against Jewish welfare? And it’s a question that I would urge you all to take up. What went wrong in Holocaust education? And how do we begin the very slow process of turning that around.”

Fish, who also co-founded the Israel education nonprofit Boundless Israel, noted that respondents “consistently” said that they had not been taught about Israel in a serious, critical way. “I would make the argument that that work of serious Israel education must happen in a deeper and more sophisticated way at a younger age and allow for really critical thinking and the asking of hard questions in those spaces, not just when they go onto a college campus,” she said.

The second report presented at the event, however, indicated that there are also significant issues in the field of Israel studies on college level as well.

The study, written by JPPI researcher Sara Hirschhorn, examined the Israel studies field, finding that it too is going through an “identity crisis.”

Hirschhorn explored the history of the field, which developed “organically” in the 1980s as independent researchers began studying modern Israeli history, society and culture.

“Its open-tent philosophy allowed many different fields of academia, different disciplines to create a new shared sense of community around the understanding of Israel studies and also different pedagogical approaches to how to teach Israel studies in the classroom,” she said at the event. “But what began as a kind of open-ended experiment has led to an identity crisis in the field of Israel studies, in which today it doesn’t methodologically know who or what it is.”

Hirschhorn noted that Israel studies has increasingly taken a turn “towards self-criticism and even self-excoriation,” unlike other university ethnic studies programs that are explicitly aimed at instilling pride.

“The belief it could be politically disinterested was always a fiction,” Cary Nelson, a professor at the University of Illinois, who has written extensively against academic boycotts of Israel, said at the event. “[The field of Israel studies] was not originally neutral on Israel’s right to exist, and of course it isn’t neutral any longer. It is simply reversed. As all of us likely know, the field itself, along with Jewish studies, is not now merely politically split, but potentially substantially polarized. In some settings, it is thoroughly anti-Zionist. But the objectivity ideal for Israel studies also meant that Israel studies kept its distance from any mission of identity reinforcement for Jewish students.”

In her report, Hirschhorn called for Israel studies programs to reconsider this nominal “apolitical” stance — noting that the field anyway embraces post-Zionism or anti-Zionist attitudes already — and to “undertake a meaningful exchange on whether Israel Studies can and should continue to be unconcerned and unresponsive to ideological challenges within and beyond the university.”

Addressing potential donors, Hirschhorn also called for further support to strengthen and expand the field as part of a broader effort to create “more balanced narratives and healthier discourse” about Israel and Jews on campus.