Opinion

NUMBERS GAME

The real rabbinic crisis

Once again, it’s rabbinic hiring season.

I’m not sure if you’ve heard, but there is a massive shortage of non-Orthodox rabbis.

This issue has been widely covered in the Jewish press. And I’ve got bad news: With a generation of rabbis nearing retirement and fewer students entering non-Orthodox rabbinic programs, the situation will likely worsen in the coming years, perhaps decades. This trend is troubling enough — but the response is more disturbing if we aim to solve the problem.

Leaders often fail because they never interrogate their theory of the problem, the hypothesis for why there is the problem in the first place. When people opine on the hiring crisis, familiar themes arise:

- We need new rabbinic programs.

- We have too many rabbinic programs.

- We make it too easy to enter the rabbinate.

- We make it too difficult to enter the rabbinate.

- We should blame Reform and Conservative Judaism.

But like any weak theory, each explanation fails because it sees this crisis as the result of a specific villain instead of a failure of an interconnected system, about which each of these potential causes plays some role but not a singularly impactful role. Unless the theory considers how institutions interact with one another, the rabbinic crisis is unlikely to improve.

Let’s begin by taking a journey on Amtrak that went horribly wrong.

Cascading failure

In August 2003, I was about to board a train at New York Penn Station when the lights went out.

This was the Northeast Blackout of 2003, which covered 3,700 miles and started because of a power failure in Detroit, Michigan. For those who study power grids, this is what’s known as a “cascading failure,” where “failure of a part [in an interconnected system] can trigger the failure of successive parts.” Energy flows throughout a power grid, and although two sections may be geographically far apart, the right sequence of events can bring the entire system down.

Individual Jewish journeys are the product of the efforts of an array of Jewish institutions that vary in size, location, ideology, denomination and approach; and yet, despite our interconnectedness, we rarely discuss cascading failure in the Jewish community. When we observe a negative trend, the most likely reason is a systemic failure of various actors who may not even realize how much they impact one another.

Consider my rabbinic journey.

Don’t forget the denominator

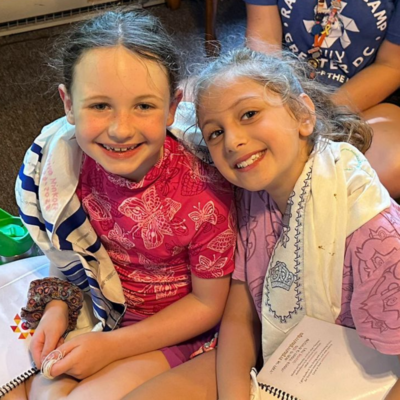

I grew up going to a large Hebrew school. Of my graduating class of almost 50 students, I became a rabbi, and one other graduate became a cantor. That year was an outlier, however; more often, not a single graduate joined the clergy.

This is not a critique of my childhood synagogue, but rather to point out that, even under the best of circumstances, most Jewish children are not going to become rabbis or cantors.

But, consider the math:

If your Hebrew school averages 50 students per year and only two become clergy in ten years, the “success” rate in that period is only 0.4%. If the average enrollment drops to 20 students per year, the percentage of students who become clergy is more likely to remain constant than increase or decrease. Thus, if the number stays constant in that same 10-year period, a success rate of 0.4% will yield only 0.8 students becoming clergy.

In other words, if there are fewer participants in non-Orthodox Judaism over time, there will also be fewer clergy. Whether we have “enough” rabbis depends on ordaining “enough” relative to the total potential population.

This tension is a cognitive bias known as the base rate or denominator fallacy. Today, we focus on increasing the numerator — the number of clergy — while ignoring its relationship to the denominator — the total number of potential non-Orthodox Jews who might become clergy in the first place.

If this conclusion seems obvious, it is.

Everyone knows that non-Orthodox Jews’ engagement is depressed at every level. However, if we take this statistical reality seriously, we would address the problem differently by ensuring that every stage of the Jewish pipeline is robust and well-funded to maximize the potential number of future clergy in a shrinking population.

And here’s where we come to the crux of our problem.

Systemic non-investment

We can’t anticipate when someone will deepen their commitment to Jewish life; kal va’homer, all the more so, if and when they decide to enter the rabbinate. But the longer a person goes without Jewish engagement, the less likely they are to start. Thus, our time and money should be spent intervening as early as possible with the largest number of Jews before we start falling behind in the count.

For over three decades, however, the Jewish institutional world systematically neglected the very institutions we need to thrive to maximize our chances of richly educating the most significant number of Jews such that they might choose the rabbinate.

- Early childhood education: Fewer synagogues run preschools, meaning fewer young children and parents are exposed to Judaism daily at an early age.

- Supplementary education: Despite being the largest provider of Jewish education to children, Hebrew schools remain underappreciated and undersupported financially. They are often treated as the paradigm of what “bad” Jewish education looks like, regardless of whether or not that’s true.

- Teen engagement: Today, there are only two viable organizations for Jewish teenagers with global reach, as the ones that could offer alternatives have been financially starved from without and within.

- Synagogues: Despite being the most affiliated-with Jewish institutions by a wide margin, synagogues continue to be ignored as a model in place of new spiritual paradigms that, while impressive, have not shown the capacity to scale beyond major metropolitan areas.

Camps and day schools are exceptions that prove the rule. Camping is the only sector of Jewish life where a concerted effort was made to strengthen the entire field, and the fruits of that strategy are readily apparent. However, this effort has not been replicated in any other sector. While Jewish day schools provide the most significant amount of Jewish learning time for Jewish children, tuition sticker shock makes substantial enrollment increases to replace losses in every other sector highly unlikely.

The rabbinic crisis, seen through this lens, finds a different villain.

The local Jewish institutions that create the pipeline for Jewish children to become future clergy grow smaller and weaker with each passing year. As the total number drops, so does the total number of clergy. The current shortage results from a cascading community failure due to systemic underinvestment.

None of this minimizes the tremendous value of investing in Jewish college students and young adults. However, many of these organizations are already tasked with re-engaging Jews who were turned off by the Judaism of their childhood, meaning that they are often cleaning up after previous negative experiences. It’s impractical to assume that these institutions can, on their own, fix the broken pipeline.

We cannot innovate our way out of this problem by creating another cohort, fellowship or conference, nor can we hope that some new paradigm will emerge to replace all existing institutions. While creating terrific content is invaluable, no one can provide content if the institutions disappear. The only way to address this problem, which has enormous implications for the Jewish world, is to stop ignoring the infrastructure and legacy institutions and give them the resources they’ve always deserved but rarely received.

Lessons from Joshua ben Gamla

In Bava Batra 21a, our Sages credit Joshua ben Gamla with ensuring the vibrancy of Torah learning when he decreed that Jewish children should begin their studies at age six. In Maristella Botticini and Zvi Eckstein’s The Chosen Few: How Education Shaped Jewish History, they argue that, over time, this decision to start requiring education at an early age is what allowed the Jewish people to become “a small population of highly literate people, who continued to search for opportunities to reap returns from their investment in literacy.”

Non-Orthodox Judaism operates in an environment similar to the one Joshua ben Gamla encounters: There is institutional decay coupled with a Jewish populace largely deficient in Jewish literacy. Like in Joshua ben Gamla’s era, we will not innovate our way out of this problem, because the problem is not about innovation — it’s about our collective negligence of the institutions whose success or failure holds the key to whether or not we will find a solution.

Today’s rabbinic hiring crisis results from failures at every level of Jewish life; no single institution caused it, nor can any one institution solve it. The only way to fix it begins with changing our attitudes about the phases of the Jewish pipeline that need professional, intellectual and philanthropic attention that they sorely lack. Anything less is a dereliction of duty to foster a vibrant Jewish future.

We cannot wait any longer.

Rabbi Joshua Rabin is the rabbi of the Astoria Center of Israel and the author of Moneyball Judaism.

Add EJP on Google

Add EJP on Google