The Power of Blended Learning in the Jewish Studies Classroom

By Rabbi Reuven Spolter

Recently, a respected Jewish educator raised the following question on an educational forum.

“How much time and effort do you put into making Torah relevant to your students’ lives, as opposed to imparting knowledge and teaching skills?”

This might be the most fundamental question vexing Jewish educators today.

A debate ensued, but most agreed that schools must first make Torah relevant. Teachers argued that only if our students feel that Torah is important to their lives will they want to study it at all. This makes intuitive sense. How can we expect our students to learn Torah if they don’t connect to its teachings?

The question places two critical educational goals at odds with one-another: relevance versus knowledge and skills.

We can frame it another way: Should we emphasize emotional connection to Judaism or intellectual connection? Is it more important to hold a kumzitz so our kids will be passionate and feel connected to Judaism, or a study session giving them more insight and greater knowledge about their heritage?

Can’t it be both? Can’t we teach our students knowledge and skills while also imparting within them a sense of love and passion about their heritage?

Sadly, too often, the answer today is “no.” This is by no means the fault of Jewish studies teachers, who would love nothing more than to pull apart a complicated Rashi or study a difficult piece of Gemara. Due to significant changes taking place around the world – the proliferation of screens, an increased unwillingness to read text of any kind or length – many children find it increasingly difficult to engage in serious reading, even in their native language. Jewish schools face the even more daunting challenge of educating students to master ancient Jewish texts. Moreover, the Hebrew of Tanach and Mishnah is not really modern Hebrew, to say nothing of the Aramaic of Talmud or Halachah.

Even when teachers do tackle teaching text in the classroom, this often comes at the expense of connection. After the grueling work of teaching the basic mechanics of a text, little time (or energy) is left for the next level, the meaning that comes from the text. So teachers often opt to skip the step of text-skill acquisition and give a short synopsis, so that they can engage their students with the deeper thinking and higher order skills that bring intellectual excitement and meaning.

An International Challenge

This problem is not just a Diaspora problem. It’s a global issue that educators in Israel face as well.

In the Diyyukan in a recent issue of Mekor Rishon newspaper, Rabbi Moshe Lichtenstein, Rosh Yeshiva at the Har Etzion yeshiva in Israel decried the declining state of textual Gemara learning in the average Israeli high school. He said,

“The bitter reality is that the study of the Gemara in high school yeshivahs is eroding. In the Chareidi-Leumi sector, the situation is different, but in the National Religious public, they give a low-calorie Gemara diet, and when a person eats low-calorie, he remains skinny. The volume of material studied is in constant decline, dealing with light, popular and seemingly more attractive tractates, and the result is that students have difficulty reading basic texts. The order of the hour is to establish scholarly high schools, because it is lacking today…

In fact, there is one very pretentious thing here: an attempt to study ancient texts in the source language. The general world despaired of it after World War II. Instead of breaking teeth and learning Greek or German to end up reading twenty lines of Homer or Goethe, the perception today is that it is better to read all of Homer or Goethe in translation. So maybe it’s more effective, but in translation you mostly get the insights, and lose the living affinity for the text. You are not in dialogue with him, you have lost the unmediated contact.”

What is true for Israelis is doubly true for Jewish teachers and students throughout the Diaspora.

Yet, I think that there can be a middle ground.

There is a way to try and overcome the daunting challenge of text study without sacrificing meaning. There’s a way to harness the power of modern technology to bring text learning to students before they step into the classroom.

The solution is called “Flipped Learning.”

The Benefits of Jewish Studies Flipped Learning

In the Flipped Learning model, students learn basic skills through educational video, gaining a basic understanding of a concept. This model, popularized by Salman Khan and the world-famous Khan Academy, enables students to learn challenging educational material at home and then spend class time doing practice exercises, when they are under the tutelage of teachers who can give guidance and offer help when necessary.

For Jewish Studies Flipped Learning, the classroom can and must be so much more than that.

Imagine a classroom where the teacher, instead of teaching the students how to read and decode the text, was confident that her students had already learned the text sufficiently to be able to read and follow it inside. That is what the power of Flipped Learning can bring to Judaic studies.

Rather than try and teach twenty or thirty students at different academic levels in an integrated classroom, a teacher using a Flipped Learning model can assign the students to watch a pre-lesson and learn the text at their own pace, answering questions about the text as they progress. The teacher gets immediate, real-world feedback about each student’s progress, and can identify students who are struggling or whether a specific element of the text needs greater explanation and attention.

In a Judaic Flipped Learning classroom, students have already read the text and answered basic questions about phrasing, vocabulary and understanding. The teacher can begin the class at exactly the point that’s most interesting. Instead of teaching the “what,” a teacher can begin with the “why” and “how,” leading to a far more engaging learning experience.

Using Talmud Study as an Example

Torah learning takes place on a series of levels, building one on top of another. Let’s take the study of Talmud as an example. Talmud study, like most Jewish text learning, happens in a series of levels.

- First there is the most basic challenge of the text; of simply decoding the meaning of the words.

- The second step is understanding the logic of the Gemara – what is the Gemara trying to say through those words above that comes the interpretation of the Gemara: Why did the Gemara choose this particular line of reasoning over another? Here we reach the level of the commentaries, beginning with Rashi (another text challenge) and Tosfot, moving on from there, where the sky is the limit.

- Finally, there is the level of meaning: What is the halachic concept underlying that line of reasoning? Why did a particular rabbi rule the way that he did? How can we unravel his understanding of the issue based on that understanding?

Without the first two levels; without being able to understand the words and unravel the logic, a student will never independently be able to climb to the higher levels and truly appreciate the beauty and power of what learning Gemara is all about. But, once the two steps have already been completed, a teacher has the ability to reach the truly “fun” part of learning.

The joy in Talmud study lies in the higher order skills – the “why” of the Gemara, and the deeper sense of meaning that these questions ultimately bring.

Rethinking a Classic Model

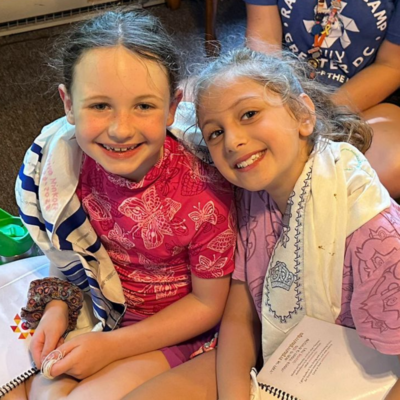

Traditional Chavruta-style learning has been a staple of Jewish education for centuries.

Truthfully, while the use of technology represents an innovation, our approach really draws from centuries of Jewish educational practice. For many years, Jewish studies teachers assigned a block of material to their students to prepare in the Beit Midrash. The students learned b’chavruta – in pairs – making a “layning” – a preparatory reading on the text. Once they had prepared, students would be ready for the “shiur” – the class where their teacher would draw upon that preparation and take the class to an entire new educational level.

Today, technology can help students do the pre-reading, giving them not only a first understanding of any Jewish text, but over time, the confidence to tackle new texts on their own.

That, of course, is the most important educational building block of all.

Reuven Spolter is the founder and director of Kitah (www.kitah.org), a new online Jewish learning platform brining Flipped learning to the Jewish studies classroom. He has served as community rabbi and taught formally and online for over two decades. He is also the founder of the Mishnah Project (Mishnah.co), an online flipped-learning initiative using the power of visual learning to bring the Mishnah Yomit program to a global audience.

Add EJP on Google

Add EJP on Google