Opinion

FULL TEXT

Let each of us view ourselves as though we personally had emerged from the Shoah

In Short

In a speech on Holocaust Remembrance Day, Menachem Z. Rosensaft quotes widely from his new book of Holocaust-inspired poetry, 'Burning Psalms'

The keynote address delivered at the Jewish Federation of Northern New Jersey’s Yom HaShoah commemoration at the JCC of Paramus/Congregation Beth Tikvah, on April 23, 2025.

Eighty years ago, my mother was at Bergen-Belsen, the Nazi German concentration camp that had been liberated by British troops only days earlier. No longer a prisoner, but certainly not yet free, she was trying to stem what seemed to be a tidal wave of death that continued after her SS tormentors had been taken away.

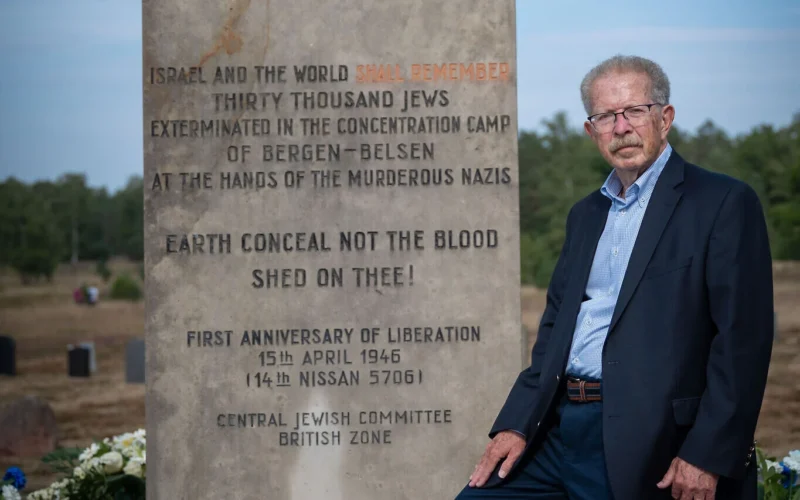

Shahar Azran/WJZ

Menachem Rosensaft at the Jewish Monument at Bergen-Belsen in 2022.

When the British entered Belsen on April 15, 1945, they encountered a devastation of humanity for which they were utterly unprepared. More than 10,000 corpses lay scattered about the camp, and some 58,000 surviving inmates were suffering from a combination of typhus, tuberculosis, dysentery, extreme malnutrition and a host of other virulent diseases.

“The hand of Adonai came upon me, declared the prophet Ezekiel. He took me out by the spirit of Adonai and set me down in the valley. It was full of bones. He led me all around them; there were very many of them spread over the valley, and they were very dry. He said to me, ‘Son of man, can these bones live again?’ And I replied, ‘O Lord Adonai, only You know.’ And he said to me, ‘Prophesy over these bones and say to them: O dry bones, hear the words of Adonai.’ Thus said the Lord Adonai Elohim to these bones: I will cause breath to enter you and you shall live again.’”

In a lecture describing conditions at Bergen-Belsen when the camp was liberated, Lt. Col. M.W. Gonin, the British officer who commanded the 11th Light Field Ambulance during the camp’s liberation, said that there were “at least 20,000 sick suffering from the most virulent diseases known to man, all of whom required urgent hospital treatment and 30,000 men and women who might die if they were not treated, but who certainly would die if they were not fed and removed from the horror camp. What we had not got was nurses, doctors, beds, bedding, clothes, drugs, dressings, thermometers, bedpans or any of the essentials of medical treatment, and worst of all, no common language.”

The liberators urgently needed help to cope with the enormity of the humanitarian task that confronted them. Brig. H. L. Glyn Hughes, the deputy director of medical services of the British Army of the Rhine and one of the first British officers to enter Belsen, appointed my mother, then Dr. Hadassah, or Ada, Bimko, a not-yet 33-year-old dental surgeon from Poland who had studied medicine in France before the war, to organize and head a group of doctors and nurses among the survivors to help care for the camp’s thousands of critically ill inmates.

For weeks on end, she and her team of twenty-eight doctors and 620 other female and male volunteers, only a few of whom were trained nurses, worked round the clock with the British military medical personnel to try to save as many of the survivors as possible. Despite their desperate efforts — it was not until May 11, 1945, that the daily death rate fell below 100 — the Holocaust claimed 13,944 additional victims at Bergen-Belsen during the two months following the liberation.

“Ezekiel continued, And He said to me, ‘O son of man, these bones are the whole House of Israel.’ They say, ‘Our bones are dried up, our hope is gone, we are doomed.’ Prophesy, therefore, and say to them: ‘Thus said the Lord Adonai: I am going to open your graves and lift you out of the graves, O My people, and bring you to the Land of Israel . . . . I will put My breath into you and you shall live again, and I will set you upon your own soil.’”

Thirty-six years later, my mother recalled the grim reality of her first days of precarious, surreal freedom. “For the greater part of the liberated Jews of Bergen-Belsen,” she said, “there was no ecstasy, no joy at our liberation. We had lost our families, our homes. We had no place to go, nobody to hug. Nobody was waiting for us anywhere. We had been liberated from the fear of death, but we were not free from the fear of life.”

By the time she was liberated at Belsen, my mother had experienced several lifetimes worth of suffering and horrors. Upon her arrival at Auschwitz-Birkenau on the night of August 3-4, 1943, her parents, her first husband, and her five-and-a-half-year-old son, Benjamin — my brother — were sent directly into one of the camp’s gas chambers where they were murdered.

“Man,” wrote Jean-Paul Sartre, “is not only that which he conceives himself to be, but that which he wills himself to be.” A human being, he went on, “is nothing other than his own project. He exists only to the extent that he realizes himself; therefore he is nothing more than the sum of his actions, nothing more than his life.”

Devastated by the loss of her family, my mother — like most of her fellow inmates and as the Germans intended — felt utterly disoriented, humiliated and deprived of her sense of self. She was forced to wear prison clothes, her head was shaved and her name was replaced with the number — 52406 — tattooed on her arm.

“I always felt humiliated and ashamed,” she wrote in her memoirs. “I hated sleeping in my clothes. I was ashamed to admit that I was hungry. I was ashamed to go to the bathroom and to be exposed half naked in front of so many other women. I was ashamed of the way I looked. I seldom spoke.”

But then a cathartic, almost surreal event occurred.

“One morning, after the roll call, a torrential rain came down,” she recalled. “We wanted to return to the barracks but instead were forced by the SS women to sit there for hours. As the rain fell down over our bodies, I realized that we were utterly helpless. Tears came to my eyes, the first ones since my arrival. When they mixed with the rain and I sat there sobbing, I found myself again.”

Because of her medical training, the notorious Joseph Mengele, Birkenau’s chief medical officer, assigned my mother in October 1943 to work as a doctor in the camp’s infirmary. There she was able to save the lives of fellow inmates by performing rudimentary surgeries for them, camouflaging their wounds and sending them out of the barracks on work detail in advance of selections.

In November 1944, Mengele sent my mother and eight other Jewish inmates of Birkenau as a medical team to Bergen-Belsen in Germany. Again, the human potential for good in the face of evil manifested itself.

Beginning with 49 Dutch children in December 1944, my mother organized what became known as a Kinderheim, a children’s home, within the concentration camp. Hela Los Jafe, another prisoner at Bergen-Belsen, subsequently remembered how “Ada walked from block to block, found the children, took them, lived with them and took care of them.”

Among them were children from Poland, Czechoslovakia and elsewhere. Some had been brought to Belsen from Buchenwald, others from Theresienstadt. Together with a group of other women inmates, my mother kept 149 Jewish children alive at Bergen-Belsen throughout the bitter winter and early spring of 1945.

According to Hela Jafe, “The children were very small and sick, and we had to wash them, clothe them, calm them and feed them. … Most of them were sick with terrible indigestion, dysentery and diarrhea, and just lay on the bunks. … There was little food, but somehow Ada managed to get some special food and white bread from the Germans. … Later, there was typhus.”

She went on: “Ada was the one who could get injections, chocolate, pills and vitamins. I don’t know how she did it. Although most of the children were sick, thanks to Ada nearly all of them survived.”

Where my mother found the strength to save others rather than focusing on her own survival has always been a profound mystery to me. Perhaps her devotion to the children at Belsen, and then, in the weeks following the liberation, to the camp’s thousands of critically ill survivors, was her way of coping with her inability to protect her own child.

“In the middle of winter,” observed Albert Camus, “I found out at last that there was within me an invincible summer.”

My father, Josef Rosensaft, meanwhile, cheated death at the hands of the Nazis several times by escaping, first from a train bound for Auschwitz, and then again from a labor camp to which he had been sent after several months in Birkenau. Recaptured, he was sent back to Auschwitz where he was tortured and beaten for months in the notorious Block 11, the so-called “Death Block.” In November 1944, he was taken from Auschwitz to a concentration camp in Germany called Langensalza, then to Dora-Mittelbau where the V-2 rockets were manufactured in vast caves carved into the Harz mountains, and from there to Belsen where he, too, was liberated on April 15, 1945. He went on to be the fiery leader of the survivors of Belsen and of the liberated Jews in the British Zone of Germany.

I begin this evening by remembering my parents because I have always seen the Holocaust, the Shoah, through the prism of my parents’ experiences. And I am quite certain that this is how the vast majority of children and grandchildren of Holocaust survivors relate to the Holocaust: by personalizing it through the stories and memories and, yes, the anguish that had been transmitted to them, to us, by our parents and grandparents.

But now we must do more, much more, than passively relating to this awareness, this transfer of memory, as it were. As the inheritors of our parents’ and grandparents’ unique, individual memories, we must forge them into our collective consciousness to ensure that we, in turn, will pass them on into the future. And I firmly believe that one critical way for us to do so — perhaps the most important and impactful — is by integrating an abiding awareness of the Holocaust into Jewish liturgy.

The biblical exodus from Egypt is said to have occurred — if it occurred at all — in the 13th century before the Common Era. Almost a millennium and a half later, the drafters of the Mishnah, the first written compilation of the Jewish oral law, mandated in their discussion of the laws relating to Passover that in each and every generation a person must view themselves as though they personally had come out of Egypt. Indeed, this is one of the central and most meaningful passages we recited at the Passover Seder less than two weeks ago.

Thus, the Jewish people’s emergence into freedom against the backdrop of Egyptian slavery looms as a formative event of both Judaism as a religion and the Jewish national identity.

However, the Exodus was not the only watershed moment in Jewish history. Talmudist and Auschwitz survivor Professor David Weiss Halivni wrote, “There were two major theological events in Jewish history: Revelation at Sinai and revelation at Auschwitz. . . . At Sinai, God appeared before Israel, addressed us and gave us instructions; at Auschwitz, God absented Himself, abandoned us and handed us over to the enemy.”

Eighty years after the end of the Holocaust, it is incumbent on those of us who consider ourselves religiously observant Jews — whether Orthodox, Conservative, Reform, Reconstructionist, or Renewal — to ask ourselves, not for the first time, the question that risks shattering our faith in, and our relationship with, God: How do we reconcile, how can we reconcile, the brutal, systematic genocide of millions of Jews with the concept of an omniscient, omnipotent, protective God whom we consistently praise and thank in our liturgy for performing miracles on behalf of the Jewish people in biblical times?

How can we praise God for saving the Israelites fleeing Egypt by parting the waters for them, when we know that the same God did not rescue some 6 million Jews from annihilation at the hands of Nazi Germany and its accomplices?

While God’s self-revelation at Sinai forms the bedrock of Jewish theology and liturgy, the absence of the Divine manifestation Weiss Halivni called “revelation at Auschwitz” — and the related theological significance and implications of this cataclysmic event — have been and are absent from our ongoing theological interactions with God. Aside from Yom HaShoah, the day set aside on the Jewish calendar for commemorating the genocide of European Jewry, or perhaps the Martyrology on Yom Kippur, the mass murder of 6 million Jewish women, men, children and infants is not featured even obliquely in our formal religious services.

These services, across the denominations, are replete with the biblical psalms that extol God’s lovingkindness, that tell us over and over that Adonai is and always has been compassionate and merciful, our rock, our fortress, our redeemer, our shield against evil and evildoers. As we read them, we are meant to be comforted by them, to feel close to God. But, in the aftermath of the Holocaust, we do not read them on our own. Hovering over us, with us, are ghosts who force us to reconsider any notions of consolation, God’s protection, or a Divine embrace.

It is against this backdrop that I set out to reconceptualize the biblical psalms in my book, Burning Psalms: Confronting Adonai after Auschwitz, published earlier this year by Ben Yehuda Press. I did not write my psalms to seek answers to the unanswerable. On the contrary, I wrote them as a Jew who believes—or wants to believe—in God, but who has been unable to harmonize intellectually or spiritually the palpable absence of God during the Shoah with the essence of God, of Adonai as portrayed in the original psalms. My goal was to try to bring the fundamental theological enigma represented by the Holocaust squarely into Jewish liturgy by invoking the ghosts who haunt us and giving them a place and a voice in our ongoing dialogue with God.

None of us can presume to know God’s essence or God’s countenance. If, however, we wish to continue to interact with God, with Adonai, after Auschwitz as Avinu Malkeinu, our parent and sovereign, in the same way we did before Auschwitz, then we have not just the right but the obligation to bring the ghosts of Auschwitz into our dialogue with Adonai.

The biblical Psalm 120 asks Adonai to “save my soul from false lips, from a deceitful tongue” before concluding with a sense of relief that “For a long time, my soul dwelled with those who hate peace, I am at peace ….” In contrast, Burning Psalm 120 takes us into the depths of the Shoah: “cursing lips/malignant tongues/pernicious words/were only/the beginning/I was shot/at ponary/inhaled zyklon-b/at birkenau/carbon monoxide/at treblinka/typhus ravaged my soul/in belsen barracks/and I am not at peace/in the grave”

Writing in early 1944, while the gas chambers at Auschwitz-Birkenau were operating in full force, Abraham Joshua Heschel asked the most basic and most critical of all theological questions: “The day of the Lord is a day without the Lord. Where is God? Why dost Thou not halt the trains loaded with Jews being led to slaughter?” This question, which was asked in one form or other by Jews in the ghettos and camps of the Holocaust, is studiously avoided in post-Holocaust Jewish religious services. It is also the very question that must, in my opinion, be transposed into precisely those services.

To a large extent, we express our faith in and devotion to God through the biblical psalms that are interspersed throughout the Jewish liturgy and in which God is consistently praised and exalted. This idyllic, harmonious relationship with and to God depends on our not confronting God with the reality and horrors of the Holocaust because we know that there can be neither praise not exultation for God in the context of Auschwitz, Treblinka, the Warsaw Ghetto, Babi Yar, or Bergen-Belsen.

My father was once asked if he still believed in God after surviving numerous Nazi German death and concentration camps. “I do not hold the Rebboine shel-oilem, the Master of the Universe, responsible for the Holocaust,” he replied, “but I won’t give Him any medals for it, either.”

I believe — ani ma’amin — with perfect faith — be’emuna shlema — in the coming of the messiah is the 12th of Maimonides’ 13 principles of faith. But how do we reconcile, how can we reconcile such absolute trust with the failure of the messiah, any messiah, to appear at the nadir of Jewish history? ?The Yiddish poet Shmerke Kaczerginski, a survivor of the Vilna Ghetto, enunciated this fundamental spiritual and theological quandary in his song, “Zol shoyn Kumen di Geule“ (Let the redemption come already) when he pleaded with the “tatele in himl,” the father in heaven, that the messiah shouldn’t arrive on the scene “a bissele tzu shpet,” a little too late.

The Burning Psalms are meant to give the ghosts of Auschwitz, the ghosts of the Holocaust, a central role in Jewish liturgy, not as shadowy intruders into our consciousness but as vocal center-stage protagonists. By attempting to reimagine the biblical psalms in their voices, I knew full well that I was treading into a perilous unknown. But I have no doubt whatsoever that in order to continue our interaction with Adonai, we must confront Adonai with these voices in our dialogue with the Divine. And perhaps, just perhaps, Jews praying to Adonai will begin to hear these voices as well.

I wrote my Burning Psalms in the hope that these ghosts of the Holocaust will become ingrained both in Jewish liturgy and in our consciousness as well as the consciousness of future generations.

I also wrote these psalms because we do not have the luxury of time. We cannot rely on future generations to carve out space for Holocaust memory as a core element of our national and religious Jewish identity. We, who have listened to and absorbed the memories of the survivors must take on this task. In doing so, we must think of the annihilated millions not as impersonal statistics but as individuals with names, faces, identities, dreams, and emotions. We cannot allow the Jewish women, children, and men who died of starvation in ghetto streets or of typhus in a concentration camp barrack, or whose corpses rose toward heaven from a crematorium to fade into the ether of oblivion.

Let us, let each of us, view ourselves as though we personally had emerged from the Shoah, and let us teach our children, and our children’s children to do the same. And let us, let each of us, commit to transmit into the future at least one name and one face from amongst the murdered millions.

For me, that name and that face belong to Benjamin, my mother’s five-and-a-half-year-old son, who was murdered in a gas chamber at Auschwitz-Birkenau on the night of August 3rd to 4th of 1943. Since my mother’s death in 1997, Benjamin has existed inside of me. I see his face in my mind, try to imagine his voice, his fear as the gas chamber doors slammed shut, his final tears. If I were to forget him, he would disappear. And I must make sure that he will not disappear with me.

And so, I would like to conclude this evening with my Burning Psalm 18, in memory of Benjamin:

a song from the dead for the dead, for the shadow, fading reflection, of Benjamin who spoke these words to Adonai on the day that Adonai did not save him from the hand of all his enemies

and he said

I once loved You Adonai

I believed

I was taught

You were my strength

my rock

my fortress where I would be safe

my salvation

Adonai, Adonai

I believed

I was taught

You are compassionate

abounding in lovingkindness

in faithfulness

in my distress I called to You Adonai

but the ground did not tremble

the world’s foundations remained unshaken

You did not roar

did not even

whisper

You did not bend the heavens

did not come down from Your palace

to lift me out of the suffocation

what did I ever do

to deserve Your silence

Your indifference?

was david

who seduced bathsheba

who sent uriah to his death

whom You did not allow to build Your temple

more faithful than I

more righteous

more blameless?

and yet You rescued david from his enemies

but left me gasping for air

gas filling my lungs

on a cold cement floor

as the cords of death choked me

overwhelmed me

dragged me to Your sheol

no Adonai

You did not protect me with Your shield

Your right hand did not sustain me

You did not set me free

did not hold me

cradle me

comfort me

therefore

You will not light up my eyes

or revive my heart

not even with a rainbow

and I will not sing to You again

Menachem Z. Rosensaft is adjunct professor of law at Cornell Law School, lecturer in law at Columbia Law School, and general counsel emeritus of the World Jewish Congress. He is the author of Burning Psalms: Confronting Adonai after Auschwitz (Ben Yehuda Press, 2025).

Add EJP on Google

Add EJP on Google