Opinion

BETTER SOLUTIONS

Don’t model antisemitism education on diversity training

Amid a major surge in antisemitism across the country, Jewish educators, advocacy groups and administrators have understandably embraced a tempting proposition: providing schools and workplaces with diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI)-style training that advances consensus positions on antisemitism within the mainstream Jewish community in institutions where Jews have faced hostility.

Let’s resist the temptation. Instead, we should offer an intellectually open, inquiry-driven model of antisemitism education — one that upholds liberal values and avoids imposing beliefs on others.

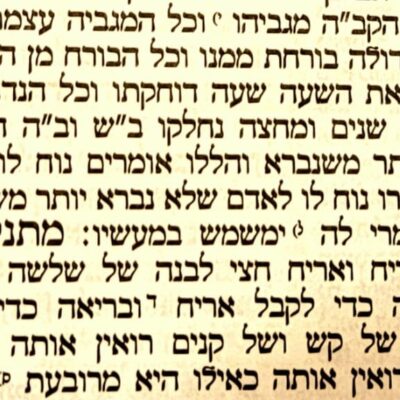

Andrew Harnik/Getty Images

A woman wears a hat that reads "Curb Your Antisemitism" during a rally against campus antisemitism at George Washington University on May 2, 2024 in Washington, D.C.

Jews rightly want antisemitism to be taken as seriously as other forms of bigotry, but the rules of the game for combating prejudice in many institutions today are broken. They are not liberal, pluralistic or evidence-based; instead, they rely on rigid ideology, compelled belief and social shaming. When we adopt those same methods to promote our understanding of antisemitism — especially on young people — we don’t cultivate understanding. We reinforce the very dynamics of ideological purity that helped produce a backlash against other diversity initiatives and fueled antisemitism.

“Training” people to adopt a particular set of views — whether about antisemitism, racism or any other contested subject — creates a coercive environment. You can train someone in Microsoft Excel. You can train someone in lab safety. You cannot train someone to adopt an argument or internalize a worldview. That’s not training. That’s indoctrination. It often backfires, generating resistance rather than fostering understanding.

Education, by contrast, engages people in open-ended exploration. It encourages them to encounter unfamiliar ideas, weigh evidence and arrive at their own conclusions. It empowers students to think — not just repeat what they’ve been told. The foundation for all education — and for a healthy liberal society — is this basic proposition: no one gets to impose their beliefs on anyone else.

We thus must draw a bright line between fact and opinion in providing antisemitism education, something frequently lacking in many other diversity training settings. The extermination of six million Jews by Nazi Germany is a fact. The recent murder of two young Israeli embassy employees at an event Washington event is a fact. The scope and influence of radical leftwing ideology on antisemitism — a subject I have written a book on — is an opinion (one supported, I argue, by abundant evidence, but an opinion nevertheless). Likewise, slavery and Jim Crow are facts; the reach and impact of “white supremacy” in contemporary America are opinions. Treating opinions as facts erodes public trust, shuts down debate and replaces inquiry with dogma.

Take, for example, antisemitism training that centers the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) definition of antisemitism. The IHRA framework has been highly useful in many legal and institutional settings. It can, for example, lend evidentiary support to a pattern of hostility faced by Jewish students when, say, a faculty member repeatedly calls to “globalize the intifada.” But it was never meant to be treated as holy writ. It’s a practical tool for determining conduct in certain contexts, not a philosophical pronouncement that ends debate. We should absolutely teach students about IHRA, but not as if it’s beyond reproach or immune to critical inquiry.

In fact, imposing a single authoritative definition in educational settings opens the door for others to do the same. As Naya Lekht, an antisemitism educator, has warned, radical actors are already crafting and promoting their own frameworks — such as “Anti-Palestinian Racism” (APR) — that define pro-Israel speech as a form of oppression. “The relationship between IHRA and APR…highlights how anti?Jewish activists learn from us — that if Jews can establish and operationalize a definition of antisemitism, architects of ‘Anti?Palestinian Racism’ can do the same,” she states. If we endorse the imposition of our ideas through DEI-style training, we legitimize the same strategy being used against us.

Another example of imposing a definition is the popular DEI mantra “Racism equals prejudice plus power.” This framework defines whole categories of people as powerless or powerful based solely on race. It reinforces a simplistic oppressor-oppressed binary that has been weaponized against Jews in the very environments where we’re trying to reduce hostility. And at the end of the day, imposing definitions rarely has the stickiness that proponents imagine.

So how should we teach students about antisemitism?

We should expose them to varied expressions of antisemitism, from far-right conspiracy theories to far-left anti-Zionist rhetoric. Students should examine classic tropes like the “Jewish cabal” conspiracy, as well as contemporary phenomena such as opposition to Israel’s right to exist cloaked in human rights language. They should be invited to explore how these ideas evolve, mutate and influence public discourse. They should be free to reject any idea, including that anti-Zionism is a form of antisemitism.

We should present diverse theories about the roots of antisemitism, including religious, economic, nationalist and ideological explanations. Instead of presenting one root cause as dogma, we should let students grapple with competing interpretations, each with its strengths and blind spots. This will equip them to engage thoughtfully with contemporary antisemitism without falling into reductionism.

For example, we should ask students to examine the domestic response and protests to the war in Gaza through multiple lenses: media representation, social media dynamics, political rhetoric and the impact on Jewish communities in the U.S., particularly on college campuses and in K–12 schools. We should encourage them to grapple with difficult questions: When does criticism of Israel cross into antisemitism? How do we distinguish between political disagreement and hate? What responsibilities do educational institutions have in ensuring both open dialogue and the safety and wellbeing of Jewish students?

This approach doesn’t water down the message. It models what liberal education is supposed to do: empower people to think, debate and grow.

We cannot defeat antisemitism by mirroring the same coercive methods that have damaged K–12 schools, higher education and civic life. Let’s reject the illiberal shortcut and rebuild trust by providing a true education on antisemitism — one that respects the minds of students.

David Bernstein is the CEO of the North American Values Institute (NAVI).

Add EJP on Google

Add EJP on Google