Opinion

Making meaning

Designing with intention: The sukkah as a relational sanctuary

In Short

With some forethought, a sukkah can be more than a hut that you eat your meals in, it can connect us to ourselves, our families and our communities

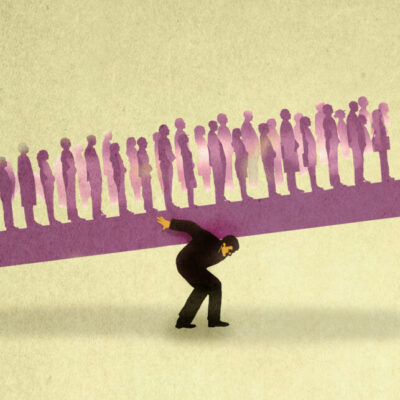

From the COVID-19 pandemic to Oct. 7, over the last few years we’ve engaged in a cycle of reactionary gathering in response to challenges facing our world. During these years, gatherings have taken many forms but have primarily centered around themes of mourning loss of life, and with it, the loss of pieces of our own identities. While we sit in this particular moment in history with immense uncertainty, holding many more questions than answers, it’s become clear that answers won’t heal us; what we’re really craving is connection.

Connection is more than just interactions with others that lead to a deeper understanding of another person. One of my favorite explanations of the term comes from the acclaimed researcher and storyteller Brene Brown, who defines connection as the energy that exists between people when they feel seen, heard and valued. Over the past few years, our ability to be seen and see others, allow for our perspectives to be heard and opinions to be valued have been overshadowed by our collective grief. Sukkot represents our profound opportunity within the Jewish calendar to reclaim what it means to proactively gather in order to reconnect with ourselves and each other in ways that allow us to help others feel more seen and understood. Only then will we finally begin to heal ourselves and the world around us. While the sukkah is designed as a temporary place of dwelling, we have a tremendous opportunity to cultivate permanent connections that last far beyond the holiday. However, these deep moments of connection don’t just happen by chance, we must find ways to intentionally design for them.

Lindsey Nicholson/UCG/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

A sukkah set up outside a synagogue in Forest Hills, Queens, New York, on Oct. 12, 2022.

Sukkot has always been associated with gathering. In ancient times, Sukkot represented one of the three holidays where Jews gathered at the Temple in Jerusalem. This holiday is also connected with a host of customs including shaking the “Four Species” — the palm frond (lulav), myrtle and willow with the etrog — in six different directions. According to an interpretation from Sefer ha-Hinukh #285, each of the four species represents a limb through which man is meant to serve God. However, I argue that this interpretation can do more than serve God, it can also serve as a paradigm to bring us into a more sacred relationship with ourselves and each other. This interpretation provides a framework for how we can utilize the holiday of Sukkot to proactively design gatherings in order to cultivate and deepen connections between people.

The palm represents the backbone, serving as one of the four species that grounds us in the holiday. The backbone of Sukkot is the opportunity to dwell with family and friends in the sukkah. While Jewish tradition guides our thinking around the construction of the sukkah’s external framework, it leaves the internal construction with more room for interpretation. If we want connection to flourish in the sukkah, we must physically design the space to reflect opportunities to be in dialogue and relationship with others. In many internal sukkah designs, a table becomes the focal point often overwhelming the physical space in the sukkah. We must re-design the layout of the sukkah to include a number of smaller gathering structures that invite us into deeper connection with ourselves and each other. Space defines place. When we reimagine the sukkah layout to include places for eating, crafting, singing, and storytelling, we invite a new depth into the space.

The myrtle represents the eyes and the ability to be enlightened. I recently saw noted psychotherapist Esther Perel live in a 6,000-person theater in Los Angeles. The moment we took our seats, a prompt was displayed on the screen inviting audience members to introduce themselves to those seated close by, and share what motivated them to attend in the evening. This invitation to connect, while seated stadium style, transformed our attendance from strangers in a theater to a community of gatherers with histories, stories and perspectives. How might we capitalize on the moment someone enters the sukkah to provide an opportunity to connect with others and become a physical part of the structure. While designing a sukkah, we have an opportunity to utilize its internal walls to create invitations in the form of photos, interactive art work, banners and symbols in order to spark curiosity that can lead to deeper connections between people. It’s only then that we can be truly enlightened by others’ stories.

The willow represents the lips, the ways we utilize our speech and the food we consume to be in a deeper relationship with ourselves and each other. Jewish tradition teaches us that it’s a mitzvah to share a meal with others in the sukkah. While delicious food nourishes our stomachs, connection with others nourishes our souls. We don’t just form deep connections with others by sitting next to them at a meal. We must utilize the meal to curate strategic opportunities to spark connection between others. Beyond assigning seats, and curating table prompts to inspire connection, we have an opportunity to utilize the food itself to showcase pieces of our own identities as Jews and people in the world. Reframing the meal through the lens of a potluck allows sukkah guests to bring a food item or dish that tells a story about who they are and ignites curiosity in others to learn more about the person they want to become.

The etrog represents the heart and soul, serving as the place where connection flourishes. We can only help others feel more seen, heard, and valued, if we can first find intentional ways to attune to our own needs. Dwelling in the sukkah invites a much needed pause in our daily lives to reconnect with ourselves. Judaism offers us profound gifts in the form of prayer and song which help ground us in our own emotions and narratives. This can look like designing a ritual to enter the sukkah with a meditative practice, creating a ritual to ground sukkah dwellers in the present by inviting them to locate the number of stars in the sky, or invitation to create our own personal blessings for the year ahead. Prayer and song not only serve as a vehicle for reconnection with ourselves, but when words fail to capture our needs, they step in as a vehicle for reconnection with others. While blessings over our meal create shared appreciation, there is no more powerful invitation to someone’s soul than singing a niggun together in the sukkah.

If we choose to design the relational elements of the sukkah with the same intention and care with which we construct a sukkah’s external structure, Sukkot can serve as the relational sanctuary that will provide nourishment and healing to us all.

Jodie Goldberg is the founder and principal of Fleurish Consulting Inc., a consulting practice dedicated to helping individuals and organizations design gatherings that deepen connections between people.