Amid Complex Climate, Israeli Non-Profits Increasingly Cooperate

by David B. Marcu

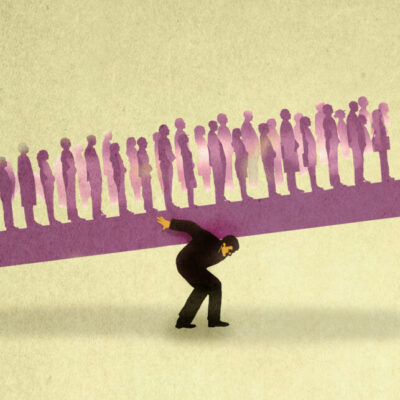

Non-profit organizations (NPO’s) in Israel are facing an increasingly difficult climate; indeed, many NPO Boards and Managers feel under siege. More than two years since the global economic meltdown, the fundraising environment is beginning to show some signs of improvement, but that doesn’t solve all of the problems for NPO’s.

As government social services are increasingly “privatized,” opportunities for NPO’s to find sources of revenue for critical human services has grown significantly in the past decade. In the “old days” it was possible to pitch funding for creative new ideas to the interested government. That direction has largely been reversed, with government seeking “suppliers” of services.

Relatively recent legislation requires that every “service” be put out for competitive bids (thus far, RFP’s are more likely issued which compare the quality of the provider rather than price). As a result, it is more complicated to bring new ideas to the attention of government professionals. Innovations developed by an NPO, if adopted by the government funder, may very well be put out for RFP, with profit-making entities and other NPO’s competing for the contract with the very NPO that initiated the idea. NPO managers may very well think twice before raising a new idea which might be “purchased” from and implemented by their competition.

NPO’s are frequently faced with unfair conditions in the RFP process. Antiquated tools are used to assess the “economic viability” of organizations applying for the contract. Such tools, designed to measure the economic viability of businesses, often include such measurements as a ratio of profit compared to assets as well as a comparison of profits to those of previous years. Since NPO’s, by definition, are not supposed to have profits, clearly this can put the NPO at a disadvantage in the RFP process. In addition, Israeli accounting procedures create complicated audited statements which never show the income from a large capital contribution, while charging the NPO with depreciation expenses for the same capital project which may have been fully funded by donations. It is not unusual for those assessing such audited reports to totally miss millions of shekels of donations for “bricks & mortar,” since they never show up as such in the books.

And it gets even better … after competing in these RFP’s, NPO’s usually must accept lower rates of reimbursement than their profit making peers. If the government determines a given price for a social service, that price is automatically increased by a given profit margin for profit-making providers. At the same time, the VAT (value added tax) system allows profit-making entities to charge VAT and then be credited for their payments of VAT, where NPO’s pay full VAT and get no credit. NPO’s, in fact, pay a special payroll tax which profit-making entities don’t pay, since the Finance Ministry believes that NPO’s must pay for the “benefit” they get for not having to charge their customer VAT. But again, the NPO indeed may not charge its customer VAT, but it pays for VAT (16%) on all its own purchases.

Finally, the financial condition of local governments in Israel has led many of them, and their chief overseer – the Interior Ministry – to seek new forms of revenue. Discounts which NPO’s have traditionally received on “Arnona” – property tax – are being cancelled. The Interior Ministry often invokes the “fact” that an NPO does not have a true “voluntary” character if most of its income is from government sources and not from donations; the same donations that often are hidden in audited statements! The Supreme Court recently ruled that an NPO that operates in a competitive environment with profit-making entities is not entitled to its traditional discount. With NPO’s paying full property tax their government funders usually do not reimburse them for the full and true cost of this tax when paying for services.

And where matters complicate even further, NPO’s are faced with all these conditions at a time when the world economic crisis made funds from donors increasingly difficult to come by.

But many service recipient focused and well led NPO’s are pushing back. Coalitions are being developed and existing ones are being energized to work on many of these issues and others. It is too early to tell if these efforts will succeed in some or all of the spheres of impact, but the good news may come from the fact that increased cooperation among NPO’s, a process that received increased momentum in the previous decade, may bring cooperation in many other spheres – including partnerships and cooperative ventures, all for the benefit of those who so greatly need the services these NPO’s provide. I believe that donors will welcome this change as well.

David B. Marcu is the CEO of Israel Elwyn, an organization that provides support services for children and adults with disabilities and their families. He is the current president of the International Association of Jewish Vocational Services, and is a member of the board of directors of the Israel Council for Social Welfare and the professional advisory committee for youth and disabilities of “Tevet”, the employment subsidiary of the JDC.

Add EJP on Google

Add EJP on Google