“Active Bystander” Responsibility: Collectivism through the Lens of Responsibility

[This essay is from The Peoplehood Papers, volume 12 – For Whom Are We Responsible? – published by the Center for Jewish Peoplehood Education.]

[This essay is from The Peoplehood Papers, volume 12 – For Whom Are We Responsible? – published by the Center for Jewish Peoplehood Education.]

by Nir Lahav and Idit Groiss

Responsibility and Individualism

Knowledge equals power. Everyone knows that. The modern world is scrambling to acquire as much knowledge as possible, and to get there first, before anyone else does. But what do we do with that power? Our conscience and Jewish texts tell us that knowledge also equals responsibility. We cannot ignore that which we know to be wrong. We’re not allowed to. Jewish Law states clearly: “Neither shalt thou stand idly by the blood of thy neighbor: I am the Lord” (Leviticus 19:16). This law obliges the bystander to go to extraordinary lengths in order to save a victim, even as far as hiring someone to help. The Talmud added the verse “thou shalt restore it to him” (Deuteronomy 22:2), meaning that it is our duty to assist even those in distress, who are not in immediate peril. The Jewish philosopher Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel (1907-1972) has decreed: “In a free society where terrible wrongs exist, some are guilty; all are responsible”. The Passover Seder itself, which we will celebrate in a couple of weeks and has been passed on from parent to child for hundreds of years, is based on the assertion that each and every generation must see themselves as though they have personally experienced the horrors of slavery, and the exodus to liberty. In the tale of the Four Sons, the third, wicked son does not actually harm anyone. His wickedness stems from his indifference to the fate of his people. “What is this to you?” he asks. “To you”, not “To me”. His individualism is penalized by an eternal label of wickedness.

Having established the basic requirement that Judaism demands of us – to take responsibility for that which we understand is wrong – we need to define what that responsibility means in practice today.

“Active” Bystanders

In the global village that is constantly shrinking, some of our closest, next-door neighbors are located on the other side of the world. The Far East, the Middle East or the Americas have become our backyard. Everything that happens somewhere influences us at home. We know what is happening at any given time in the most far-off countries, and even censorship imposed in places such as China or North Korea is showing signs of cracks, through which video clips and pictures filter and leak out. Women and children are still suffering from horrific human trafficking; greed, ignorance and corruption are standing in the way of fresh water and food supplies for entire villages; and diseases that have been banished from the western world decades and centuries ago, still continue to plague whole communities around the globe.

Again – we know all this. What do we do with this knowledge?

Ignoring this responsibility of ours on the basis of the traditional saying “The poor of your city come first” at the expense of “Tikkun Olam B’Malchut Shaddai”, means gravely misunderstanding the whole issue – as there is no conflict between these two options. The question is only of timing, or of prioritizing our social tasks, as it were. One is not achieved at the expense of the other, but rather as we work to clean up our global backyard, be it in Israel, America, India or Ethiopia, all benefit from the results – the local communities in need, the volunteers and professionals working to help them and in the process acquire significant tools for social change to implement in their home communities, and by ripple effect – everyone around them. A simple thing, like teaching a child to believe in herself, will enable her to go on and achieve things that were previously unattainable. She and others like her will contribute to her society, will learn to give back part of what they received, and this cycle will grow and expand to include more people. An American volunteer, freshly returned from working in Mexico, will have an advantageous understanding of the Mexican immigrant community in the USA, and will help to better their status from welfare dependency to active membership of their community.

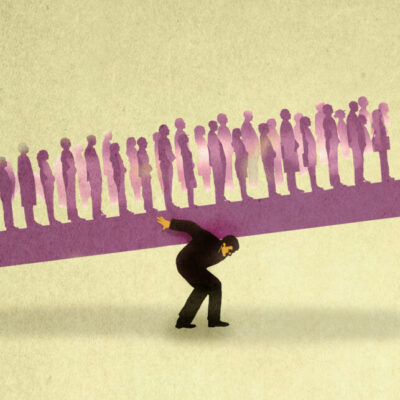

What can we do? It is true that we most likely cannot change the whole world by helping someone or promoting a cause. But by using our knowledge, in conjunction with our conscience and actions, we make the transition from passive bystanders, satisfied with just looking on at the world’s injuries, to active bystanders, who are aware of their responsibility to lend a hand and heal the world (“tikkun olam”). This is along with the humble understanding that maybe we cannot change the whole world, but perhaps just a world – the world of a child, of a family, of a community. And that is an excellent start.

Nir Lahav, is the Social Activism Director, The Jewish Agency for Israel.

Idit Groiss, Project TEN (Tikkun Empowerment Network) – Global Tikkun Olam

The writers helped found and are part of a team that operates Project TEN – Global Tikkun Olam at The Jewish Agency for Israel. Project TEN establishes volunteer centers in Israel and in developing countries all over the world, which host young Jewish adults that work and study together.

This essay is from The Peoplehood Papers, volume 12 – For Whom Are We Responsible? – published by the Center for Jewish Peoplehood Education.

This essay is from The Peoplehood Papers, volume 12 – For Whom Are We Responsible? – published by the Center for Jewish Peoplehood Education.

Add EJP on Google

Add EJP on Google