VOS MACHSTU?

While Yiddish program at Brandeis dwindles, others surge with interest

'Now I see people who are half my age who are learning Yiddish, going on the same journey, moving through the same kind of stages that I did, and it's so interesting'

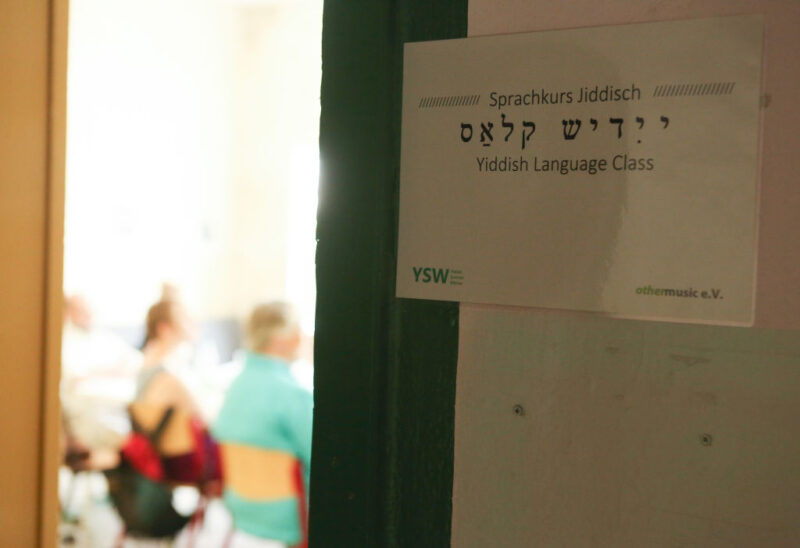

Adam Berry/Getty Images

Illustrative. A sign indicates a Yiddish language course being taught during Yiddish Summer Weimar on July 27, 2018 in Weimar, Germany.

Two months ago, a chill ran through the Yiddish community with the news that historically Jewish Brandeis University was putting its Yiddish program on hiatus. Less than a month later, after outraged emails and letters poured into the university, plans have shifted.

Instead of shuttering the Yiddish program, Brandeis whittled it down from four classes per year to two, alternating years between intro classes and intermediate and advanced classes. Meanwhile, Yiddish study is thriving elsewhere, bringing together students of all ages and backgrounds in academic settings, intensive programs and online.

“The pandemic was terrible for lots of people. It was very good for Yiddish,” Jessica Kirzane, associate professor in Yiddish at the University of Chicago and editor-in-chief of In geveb: A Journal of Yiddish Studies, told eJewishPhilanthropy. “Online Yiddish classes have connected a culture that was always diasporic and sometimes quite isolated and allowed people who are not in places where Yiddish is physically taught to have opportunities to engage with Yiddish.”

While many people study Spanish and Chinese to get ahead in business, no one is getting rich off Yiddish, Kirzane said. “It’s not a practical choice… The quality of students tends to be very high. They’re there because they want to learn Yiddish and not because they have to.”

Some of her students study Yiddish because they want to better understand Jewish or Polish history. Others want to translate books that would be lost if people couldn’t read them. Some connect to the language because of their interest in Jewish socialist and left-wing political movements. Others take courses just to be quirky, and some simply want to speak a line of Yiddish to their aging grandparents before it’s too late. Even though there is great demand, Yiddish studies “has a lot of potential to meet hard times pretty fast,” Kirzane said.

This is evident in many schools, including at Harvard, which in 2024, courted controversy when the school’s president, Alan Garber, overruled a unanimous decision to offer its only Yiddish scholar tenure. Because of a policy that caps employment for non-tenure track faculty after eight years, the program has become a revolving door for staff. It currently has no chair of Yiddish studies. But other schools are growing. In 2025, the University of Texas hired a full-time assistant Yiddish professor.

Kirzane is constantly hustling, speaking at Hillels, in German studies classes, advertising and putting on programs so students know the program is available to them. While she is a full-time employee, her position is not tenure-track.

Yiddish is “a crucial part in the training of anyone working either in American Jewish history or European Jewish history,” Jonathan Sarna, formerly the Joseph H. & Belle R. Braun Professor of American Jewish History at Brandeis University, who retired this year after 35 years of teaching, told eJP.

Many Jewish languages are on the verge of disappearing, he said, referencing distinctly Jewish dialects throughout the Middle East. This lack of appreciation for languages is a particularly American problem, he said, unlike in Europe, Latin America or Israel, where it is expected that you need to know multiple languages to interact with the larger world.

Even in Israel, which historically maintained a complicated relationship with a language that is seen as fundamentally diasporic (unlike the native revived Hebrew), interest in Yiddish is surging, Sarna said. “Once upon a time, there was great embarrassment about Yiddish, and it seemed heretical to push Yiddish when the language of Zion was Hebrew and so on,” he said. But now that Hebrew is the norm, “there’s nothing to fight about anymore, and there can be a rediscovery of Yiddish, which [to many young Israelis] is as exciting as discovering unknown works in the Cairo Geniza.”

After all the shifts in programs at Brandeis and Harvard, “one hopes that when the dust settles, there will be even more opportunities to acquaint students with Yiddish civilization in all its glory,” Sarna said. “Perhaps some of the new technology will both excite [young students of Yiddish] and make it an intensive and therefore more successful experience [than in the classroom setting] and even do it perhaps for a lot less money.”

Online Yiddish learning especially surged when the world shut down during the pandemic. Between spring 2020 and spring 2022, the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research grew from running four spring Yiddish classes to 40. Today, it runs intensive summer and winter programs as well as around 30 classes with over 300 registrants every spring.

Interest in the summer program, especially, is “incredibly diverse,” Ben Kaplan, director of education at YIVO, told eJP. “The youngest student might be 16, still in high school… Oldest student might be in their 80s. Everyone learns together, which is a beautiful, impactful thing. It’s rare to get that kind of intergenerational learning.”

The Yiddish Book Center and Tel Aviv University also put on summer intensives. Even non-Jews attend.

“Sometimes an older generation meets one of our young people and says, ‘Gee, you’re not Jewish. Why are you learning Yiddish?’ And [the young student will] say, ‘Why is it that people don’t ask that of you when you learn other languages,” Susan Bronson, president of the Yiddish Book Center, told eJP. “Why shouldn’t non-Jews learn Yiddish and learn about the history? It’s like studying the history of any people in any culture.”

It was whispered through the Yiddish community that Brandeis was considering using another organization’s already existing online learning program and/or intensives as ways to fill their gap during the period the program was thought shuttered. (Sources at the university told eJP that they themselves could not consider the school a full Judaic studies program without its own Yiddish program.)

Because there are so many options to study Yiddish, the Yiddish Book Center focused on supporting teachers as well as students. Historically, Yiddish teachers are often people who are very passionate, but who aren’t trained in teaching secondary languages, so the Book Center offers a yearlong Yiddish Pedagogy Fellowship.

The center also created “the first modern Yiddish textbook based in the communicative approach to language learning, which is one of the most important contemporary approaches to language pedagogy,” Bronson said. “Yiddish language teaching should be treated as seriously as any other language.” They hope that their pedagogy program will “become the heckscher [stamp of approval] for Yiddish teachers.”

All these programs and ways of learning serve a purpose, said Kirzane. “A community class might be more oriented toward using Yiddish for creative purposes or for genealogical study or for pleasure reading. And then a course in the university might be more tailored toward people who are interested in pursuing research. I don’t think that one is better than the other.”

The Brandeis issue is reflective of American society’s view of Yiddish as a whole, Rokhl Kafrissen, a Yiddish teacher, journalist and playwright who studied Yiddish at Brandeis from 1993-1997, told eJP.

Brandeis “epitomizes American Judaism, American Jewishness,” she said. “Their Jewish studies department is very good. It’s very well-known. And Jewishness is a certain thing, and you realize that Jewishness is a certain thing with a boundary around it when you yourself fall outside of that boundary… the school didn’t take it very seriously. If you told people at Brandeis that you were studying Yiddish, nine times out of 10 you were met with a reaction of, ‘Ooh, what are you doing? Why?”

But the same way her passion for the language couldn’t be stifled, the new generation is hungry to learn. “When you get it into the Yiddish scene, you’re the young person in the scene for a long time,” she said. “And it’s weird, now I feel like I woke up one day and I’m like, ‘Oh, wait, I’m not young anymore.’ Now I see people who are half my age who are learning Yiddish, going on the same journey, moving through the same kind of stages that I did, and it’s so interesting.”

Passion for Yiddish “will only grow,” she said. “The problem is that it’s so hard to convince people to invest money in it.”

Another obstacle Yiddish studies faces is being “caught between these cultural wars, Zionism versus anti-Zionist,” Eli Rubin, a cultural historian and an editor at Chabad.org who ran a Yiddish translation fellowship with Chabad at Princeton this year, told eJP.

There is a myth that all those who study Yiddish are raging anti-Zionists, he said. But, just like in the old world, those who speak it run the gamut politically. “Yiddish has been a way for people to cultivate a Jewish identity that’s outside of the kind of the dichotomy of Zionism versus anti-Zionist. You can just be Jewish in Yiddish space. Which is really how Judaism always was. Going back centuries Yiddish wasn’t defined by the binary of Zionist versus anti-Zionist, which is a very modern thing. It became a debate that’s been incorporated into Judaism, but it’s a debate that’s kind of threatening to overtake Judaism.”

Rubin, like many in the Chabad movement and in other Hasidic groups, attended classes completely in Yiddish as a kid. The Yiddish studies community, he said, “brings together people who wouldn’t necessarily otherwise be in a room together,” making it “one of the friendliest corners of Jewish studies.”

Add EJP on Google

Add EJP on Google