Opinion

FROM THE CHEAP SEATS

What Cirque du Soleil taught me about donor stewardship

On a recent trip to Las Vegas, my wife and I decided to see “Michael Jackson ONE,” a Cirque du Soleil show that promised iconic music, dazzling visuals and gravity-defying acrobatics. We were in the “cheap seats,” third row from the back, and as we settled in, we gave each other the universal reassurance of budget-conscious theatergoers: “These seats aren’t so bad…”

But then the show began.

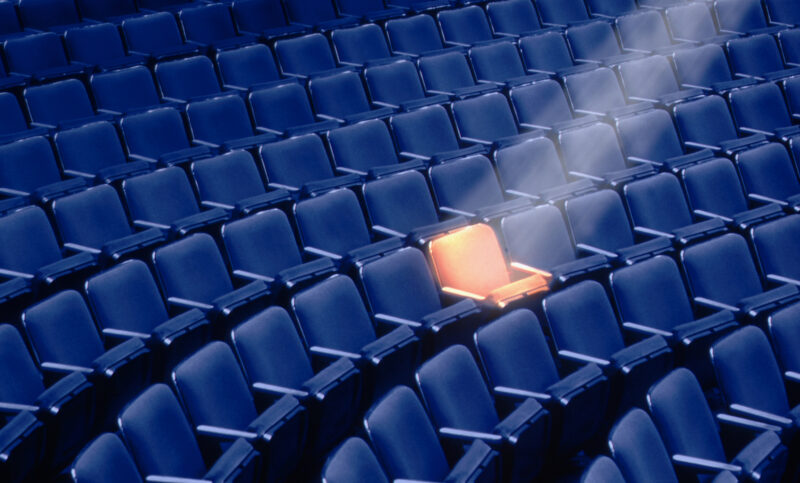

Benjamin Rondel/Getty Images

Performers danced in the aisles around us. Acrobats descended not just from the stage, but from above our heads. Floor-to-ceiling projections blanketed the walls, and hidden LED panels emerged from the ceiling throughout the theater to immerse us in the story. We weren’t just watching the show from the cheap seats. We were watching a show designed for the cheap seats.

Halfway through, I found myself wondering something unusual: What were the people in the front row missing by having such “great” seats?

The nonprofit imagineer in me noted that someone at Cirque du Soleil must have asked a bold question: How can we make this as thrilling for the people in the back row as it is for the people in the front row?

That same question should guide our approach to donor engagement, especially now, as we head into back-to-school season and then the High Holy Days, when so many organizations launch their annual campaigns. As we aim for full retention as well as new donor acquisition, this is our moment to ask bold, creative, even unreasonable questions about how we make every donor feel connected, seen and essential.

The ‘front row bias’

Let’s be honest: it’s natural to prioritize big donors. According to the Generosity Commission’s 2024 report, “year over year more money has been given to nonprofits, but by fewer givers,” a trend sometimes called “dollars up, donors down,” which underscores the growing reliance on major donors.

This shift mirrors the widening wealth gap in society at large. A smaller group of individuals now holds a growing share of philanthropic power, while more people are giving less, or not at all. But that doesn’t make the smaller contributors any less meaningful. In fact, if we focus only on the top tier, we risk building a future that rests on an increasingly fragile foundation.

After all, big donors may be funding today, but small donors will shape tomorrow.

With the right care and connection, today’s $18 giver can become tomorrow’s $1,800 supporter, or the board chair leading your next capital campaign.

But without that care, they can just as easily drift away, feeling unseen, unappreciated and unlikely to give again. If we want to build sustainable, future-ready communities, we need to treat every donor like they matter – because they do.

Often, big donors are invited to appreciation dinners, receive handwritten notes, get personal calls and enjoy inside access, while smaller donors are left behind. That’s not inherently wrong. There are only so many breakfasts a rabbi can set aside for donors… A line needs to be drawn somewhere.

But what message are we sending to the donor who gives $18, or signs up for a $10/month recurring gift? Are they left watching the show from the back row, somewhat appreciated, but mostly disengaged?

What if we asked the unreasonable question: “How do we make a $10 donor feel just as important as a $10,000 donor?”

Reimagining the cheap seats

Let me be clear: This isn’t a call to equalize the donor experience. Your $50,000 donor and your $50 donor don’t need the same thank-you gift or recognition package, nor should you abandon the system that you’ve built for major donor stewardship. But, they do both deserve to feel seen, appreciated and respected.

At The Lapin Group, we work with clients not just on major fundraising campaigns, but on reframing their development strategies to embrace this kind of intentional inclusion. In a recent meeting with one of our synagogue clients, we discussed how their Volunteer Shabbat was surprisingly under-attended. Why weren’t volunteers showing up to be honored? They learned that their volunteers simply didn’t want fanfare. Regardless of the amount of support they contributed, they weren’t looking for applause; they were acting out of belonging. As the senior rabbi put it, “They told us ‘this is what you do for your family.’”

This synagogue offers a powerful reminder that many people don’t give or volunteer because they want to be elevated — they do it because they already feel included. That mindset flips the script. Instead of asking how to “honor” someone in the cheap seats the same way we would in the front row, we can ask how to make them feel just as seen — to design an experience that reinforces their place in the story — not because of their donation amount but because of who they are. When we lead with belonging, we stop focusing on who’s in the front row and start focusing on whether everyone feels like they’re part of something that matters.

On being unreasonable

At this point, you may be thinking, “Do you know how many small donors we have? I’m already overwhelmed. This all sounds nice, but what you’re asking for is unreasonable.”

To which I say, in the immortal words of The “Princess Bride”’s Inigo Montoya:

“You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means.”

In his book Unreasonable Hospitality, Will Guidara challenges leaders to go above and beyond to make people feel truly valued. He writes:

“People will remember how you made them feel long after they’ve forgotten what you gave them. And how you make them feel is often in direct proportion to how much effort you put in.”

Unreasonable is not about extravagance. It’s about effort, intentionality and empathy.

Unreasonable isn’t the obstacle. It’s the objective.

This mindset shaped much of what emerged from the first cohort of USCJ’s Sulam for Imagineers, a training program that I run for synagogue professionals and lay leaders committed to tackling engagement challenges through creativity, collaboration and bold thinking. At its heart, Sulam for Imagineers encourages leaders to embrace the unreasonable — to push beyond what’s easy or expected and design experiences that truly make every member feel valued and connected.

Imagineering your unreasonable annual campaign: A few ideas

As your organization gears up for the High Holy Days and annual fundraising, here are a few not-so-unreasonable ideas to help every donor feel like they’re in the front row:

- Get proactive with your outreach. Rather than waiting to send a thank you letter after the gift is made, reach out now — before the start of the new year — with a personal note of appreciation for being a part of the community. No reminders or agenda; simply a moment of connection to ensure everyone feels seen and understands that they are an important part of your organization’s story.

- Design donor “roles” instead of tiers. Instead of bronze, silver and gold, imagine naming donor groups after values, story archetypes or community roles. Let donors see themselves in your mission, without hierarchy to make them feel less-than.

- Personalize thank-yous with micro-stories. Don’t just say thank you. Say, “Your gift made it possible for one student to join our youth group retreat.” Even small donors should feel like their gift made a difference.

- Send a “welcome to the family” kit to first-time donors. It doesn’t need to be fancy. Just something that says, “You belong here, and you matter.”

- Ask unreasonable questions. Instead of “How do we thank people?” ask “What’s an unforgettable experience we can create for someone giving $10 a month?” Instead of a closed-ended question like, “Is it possible to give a personalized thank you to every donor?” ask, “What are some fun ideas to personally thank every donor?”

Back in Las Vegas, Cirque du Soleil kept the cheap seats affordable but made the experience unforgettable. Not by moving us closer to the stage, but by expanding the stage to meet us where we were.

That’s the charge for Jewish nonprofits today: Expand your stage. Create awe and belonging at every level of giving. Make the $18 donor feel like they’re an integral part of something extraordinary, because they are.

In the end, the measure of a great experience isn’t how much you paid to see it. It’s how deeply it moved you.

Ben Vorspan is the author of The Nonprofit Imagineers and a consultant with The Lapin Group.

Add EJP on Google

Add EJP on Google