Opinion

The Torah of leadership

Taking the lead: Thoughts on Parshat Tazria/Metzora

In Short

As leaders rise in the hierarchy, they run the risk of being increasingly insulated from key information because people are taught to bring them solutions, not problems. To be resilient, you must be informed.

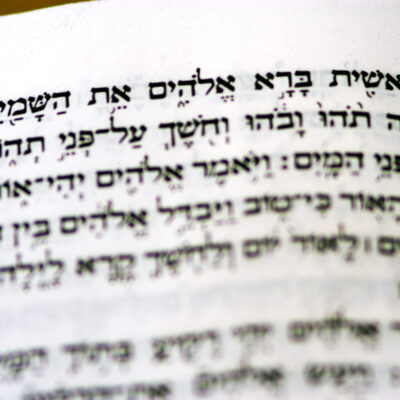

This double Torah reading of Tazria and Metzora is among the most challenging in the Torah. It is about a spiritual skin affliction that we erroneously call leprosy, its many variations and the places it can reach: one’s body, one’s clothing and even one’s house. Instead of going to the ancient equivalent of a dermatologist, the person infected notifies the Kohen Gadol, the High Priest. If the illness is spiritual with a physical manifestation, then the doctor, too, must be a spiritual one. Who better than the High Priest to diagnose the rash?

“When a person has on the skin of the body a swelling, a rash, or a discoloration, and it develops into a scaly affection on the skin of the body, it shall be reported to Aaron the priest or to one of his sons, the priests. The priest shall examine the affection on the skin of the body: if hair in the affected patch has turned white and the affection appears to be deeper than the skin of the body, it is a leprous affection; when the priest sees it, he shall pronounce the person impure.” (Lev. 13:1-2)

Courtesy

The priest has the unenvious job of declaring the sufferer impure and has the more promising job of declaring that same person free of tzara’at when the inflammation disappears: “…the priest shall pronounce the person pure. It is a rash; after washing those clothes, that person shall be pure” (Lev. 13:6). Rabbi Abraham ibn Ezra on 13:1 writes that, “This commandment was directly communicated to Aaron because all human maladies shall be determined according to his pronouncement. Aaron shall declare who is clean and who is unclean.” The fate of this sick person weighed on the priest’s shoulders.

On the same verse, Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch observes that “naming Aaron next to Moses at the introduction to certain laws…is to indicate the quite special importance of these laws, not only for the theoretical understanding of these laws and the establishment of them for practical use in life … but also for the training and education of all the individual people…” What education might the community need from Aaron’s inclusion in this supervisory role?

When it comes to this diagnosis, we might expect three people to weigh in on the problem because in most cases of Jewish law, a person presents his or her case before a beit din, a Jewish court of three. In two places in the Talmud, however, we learn that only one priest is necessary to determine this malady: “The verse states, ‘And he shall be brought to Aaron the priest or to one of his sons, the priests’ (Lev. 13:2). Learn from this that even one priest may view leprous marks’” (BT Nidda 50a, BT Sanhedrin 34b). One priest alone is trusted in this role. Again, our question is why?

One answer may lie in a distinction Rabbi Jonathan Sacks makes in his book Ceremony & Celebration between the role of a prophet and that of a priest: “The prophet lives in the immediacy of the moment, not in the endlessly reiterated cycles of time… The priest represents order, structure, continuity, the precisely formulated ritual followed in strict, meticulous obedience.” Assigning the priest the task of identifying tza’rat, leprous boils, and then declaring the disease over is a way to reinstate order into a situation of chaos because everything that surrounds the sufferer is at risk of infection. Rabbi Sacks continues his description of the priest’s foundational orientation: “For the priest, the key words of the religious life are kadosh, holy, and tahor, pure. To be a Jew is to be set apart: That is what the word kadosh, holy, actually means. This in turn has to do with the special closeness the Jewish people have to God…” We can extrapolate from here that because the priest is exquisitely sensitive to purity and can make fine distinctions between what is pure and impure, it only takes one priest to make the designation.

Another approach is to think of the priest in this role as a leader doing a job that others may shun for fear of infection. The declaration was likely humiliating to the individual afflicted, alienating him society and from those he loves. This fear of disease may have also led others to marginalize the leper and refuse to usher him back into the community at the earliest possible time. We can trust that one priest, sanctified and prepared to face the challenge, would do his very best to ensure fair and efficient treatment because he represents God. Of all people, it is the priest who should see the divine in others and remove any barrier to achieving godliness.

The priest, by modeling these difficult activities, also helped others reintegrate the sufferer. After all, if the holiest person in the community declares a person afflicted safe to return to normal life, then that declaration must be good enough for everyone. The leader sets the standard of care and concern for others. Dr. Tracy Brower claims that, “One of the most significant responsibilities as a leader is to model the way” (“How To Lead Through Hard Times: The 5 Most Important Things To Know,” Forbes Aug. 16, 2020). When it comes to managing others, she writes, “People pay attention to you as a manager — perhaps more than you realize — including what you say, how you react and the decisions you make.”

She also adds that when leading through hard times, the leader must stay “connected to key information. As leaders rise in the hierarchy, they run the risk of being increasingly insulated from key information because people are taught to bring them solutions, not problems. To be resilient, you must be informed, so do all you can to ask for difficult details as much as you seek solutions.” The priest’s knowledge of every boil and scale and his intimate involvement with all stations of society in this diagnosis kept him connected to key information and close to those he ultimately served.

Brower makes another striking point. “Sometimes leaders may avoid asking too many questions because they fear being invasive.” She states that in one study about the mental health and wellness of employees, “…employees felt better when leaders checked in and demonstrated they cared. Take cues from people about whether they want to talk through issues, and back off if they don’t. But be clear about the fact that you are paying attention.” The priest in this week’s Torah reading asked lots of questions. He had to pay attention, and attention is something that followers crave from leaders. The questions he asked the person afflicted were a way of intently focusing on the problem and potential solutions in the life of one person from someone who cared profoundly.

Brower offers another role that leaders play in hard times. They provide psychological safety: “a feeling that employees are secure, can take appropriate risks and bring their best to their work.” Knowing that the High Priest had this body of information and would use it to ameliorate the lives of any Israelite provided psychological safety to the community.

So, as a leader, describe how you provide psychological safety and acute concern to those you lead.

Erica Brown is the vice provost for values and leadership at Yeshiva University and director of its Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks-Herenstein Center.