Agents of Change

New book examines the 8 North Americans who have reshaped Israeli Judaism

Bar-Ilan University historian Adam Ferziger tracks the leading religious figures — six men, two women — who he says can serve as a key bridge between U.S. Jewry and Israel

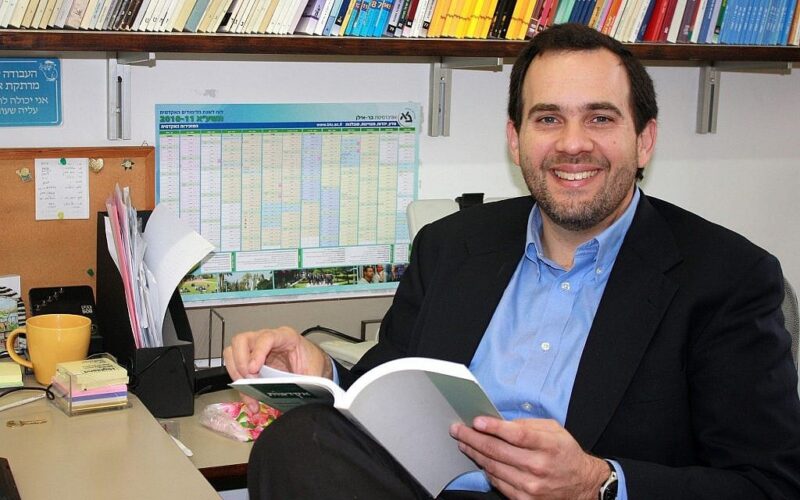

Courtesy

Bar-Ilan University historian Adam Ferziger, author of 'Agents of Change.'

For the past 50 years, a small cadre of North American Jews has been radically reshaping the Israeli religious milieu, introducing the country to a more open New World Orthodoxy, which has been changing and adapting to fit the Middle East climate.

In his new book, Agents of Change: American Jews and the Transformation of Israeli Judaism, Bar-Ilan University historian Adam Ferziger tracks eight so-called “agents of change” from their beginnings in the United States and Canada through their arrivals in Israel in the late 1960s and early 1970s and their decades of activities in Israel.

The eight changemakers are: Rabbanit Malka Bina, a trailblazer in female religious study; Rabbi Chaim Brovender, the founder of an eponymous female seminary; Rabbi Daniel Hartman, who created the pluralist Shalom Hartman Institute; Rabbanit Chana Henkin, another pioneer in female religious education; Rabbi Aaron Lichtenstein, a co-founder of the Yeshivat Har Etzion in the West Bank; Rabbi Nachum Rabinovitch, an influential posek, who ruled on issues of Jewish law; Rabbi Shlomo Riskin, who launched the Ohr Torah Stone school network, among many other things; and Rabbi Daniel Tropper, who worked to bridge the religious-secular divide in Israel through leadership development programs and activism.

Their names will be immediately familiar to English-speaking progressive religious Jews — in Israel or in the United States — but, according to Ferziger, their influence extends far beyond that admittedly small world, particularly when considering the effects that they had on their students, many of whom went off to found their own initiatives, which were influenced by their American Jewish teachers’ sensibilities.

“They all came on aliyah somewhere between 1965 and 1983. Rabbi Riskin ran around in a suit and tie and clean shaven, or [there’s a picture in the book of] Lichtenstein there with his tweed jacket. All these people, they were like Martians,” Ferziger told eJewishPhilanthropy shortly after the book was published.

“People in Petah Tikva or in Haifa or certainly in Tiberias wouldn’t necessarily know their names,” he said, referring to cities that do not typically have robust English-speaking or progressive Jewish communities. “The inflection point was when I realized that it wasn’t about them directly, it was about their students.”

This is particularly true of Lichtenstein and Yeshivat Har Etzion, whose graduates and faculty appear regularly throughout the book and whose names will be far more familiar to religious Israelis of all types. This includes Rabbi Yuval Cherlow, a co-founder of the Tzohar rabbinic movement, which works to bridge the gap between Israel’s Orthodox Chief Rabbinate and the public, and Rabbi Chaim Navon, a popular author and columnist in the country’s largest religious newspaper, Makor Rishon.

Through the Nishmat institute that Henkin founded with her husband, Rabbi Yehuda Henkin, in Jerusalem, a new type of female religious authority was created: “Yoetzet halacha” or advisor on Jewish law, who is particularly knowledgeable on Jewish law related to the sensitive topic of menstruation and family purity. These female advisers are often considered easier for women to speak with about these topics than male rabbis. Ferziger noted that in a display of American-Israeli transnationalism — the interplay between the two countries, which is a common theme in the book — many of the English-speaking graduates of this Israeli institution, which was founded by American immigrants, have gone to North American communities to serve as halachic advisors.

Similar positions have also been created through Matan, which was created by Bina, and by Brovender’s seminary, which is now known as Midreshet Lindenbaum. (The seminary is now also part of Riskin’s Ohr Torah Stone network; this type of intermixing between the various “agents of change” is a common occurrence.)

Ferziger told eJP that the influence of these figures extends beyond the formal religious world as there are fewer divides between communities in Israel today.

“Israeli religious society, as opposed to America, really doesn’t fall along denominational lines or along religious-secular lines. It’s a spectrum,” he said.

Ferziger, who holds the Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch Chair in the Department of Jewish History and Contemporary Jewry at Bar-Ilan University, is himself an American immigrant to Israel and a graduate of Yeshivat Har Etzion, with rabbinic ordination from Yeshiva University. He is also the co-convener of the annual Oxford Summer Institute for Modern and Contemporary Judaism at the University of Oxford and has lectured in universities around the world. His scholarship has focused primarily on religious communities, particularly those in Israel and the United States, and his previous books have examined these areas, as well as the Israel-Diaspora relationship. (His brother, Jonathan Ferziger, is the managing editor of eJewishPhilanthropy‘s sister publication The Circuit.)

Ferziger’s book does not delve into the Jewish philanthropists who helped support these “agents of change” and their organizations, such as Robert Beren, a major funder of Riskin’s Ohr Torah Stone network. However, Ferziger frequently notes the fundraising capabilities of many of these figures, such as Henkin and Riskin (as well as Riskin’s successor, Rabbi Kenneth Brander).

In the book, Ferziger notes two other figures that almost made the list but didn’t: Meir Kahane, the founder of the Jewish Defense League terrorist organization and Israel’s Kach political party, and Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach, whose tunes and neo-Hasidic philosophy remain popular. Though Ferziger acknowledged Kahane’s ongoing influence on Israeli society through his disciples, such as Israeli National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir, he was kept off the list as his impact is primarily political, and not religious, and because his outlook had “the polar opposite effect from that of the agents of change featured in this book.” Carlebach was ultimately excluded as, unlike the others, he did not settle in Israel but split his time between Israel and the United States. His influence also extends beyond the Modern Orthodox world, where the other figures primarily operated.

Though the book focuses primarily on these eight “agents of change,” Ferziger also examines non-Orthodox initiatives in Israel, looking at those that have succeeded in establishing themselves in Israel and those that failed.

As a case study, Ferziger looks at Beit Daniel, a Reform congregation in Tel Aviv, which successfully adapted the “synagogue-as-a-community-center” and “rabbi-as-a-CEO” model of the United States. Founded in 1991, the synagogue began offering a variety of cultural and educational activities, which its leader, Israeli-born Rabbi Meir Azari, explicitly said was modeled after the Chabad-Lubavitch emissary approach.

Beit Daniel also operated on a “fee-for-service” model, as opposed to the more common membership model, which was more appealing to the non-Orthodox public that would be wary of formally belonging to a synagogue. Through his understanding of Tel Aviv politics, Azari was also able to form connections with the city to bolster the synagogue’s activities. All of this has allowed Beit Daniel to thrive.

In contrast, Ferziger offers Tiferet Shalom, a Conservative congregation in Tel Aviv, which sought to expand in the early 2000s. The synagogue hired Rabbi David Lazar, an American immigrant, to lead the community and attract new members. Though his outreach efforts initially succeeded, his progressive politics, laidback attitude and innovative tactics irked some of the more traditional original members. He left the congregation in 2009, along with many of the newcomers who had joined him, and Tiferet Shalom — though Conservative — was eventually absorbed into the Reform Beit Daniel.

Ferziger compared Tiferet Shalom to Starbucks, which failed when it tried to launch in Israel, as it offered all of the same products that it did in the United States, rather than catering to the local market.

Beit Daniel, on the other hand, didn’t “do Starbucks,” Ferziger said. Instead, he argues, Azari created Aroma, an Israeli coffee chain similar to Starbucks, or acted like McDonald’s, “selling pita and hummus and tahina, not just cheeseburgers.”

According to Ferziger, these American Israeli “agents of change” offer more than just a window to understand the Israeli religious landscape. For American Jews who care about Israel, they can also serve as a critical bridge, a Rosetta Stone, between American Jewry and their Israeli counterparts.

“For American Jews who are not Orthodox, these people could be bridgers or can be people who can create certain types of alliances,” Ferziger said.

Add EJP on Google

Add EJP on Google