AMERICAN EXPORTS

Hadar in Israel hosts inaugural national Shabbaton as it looks to roll out expansive 5-year strategic plan

The egalitarian Jewish study organization is looking to grow its Israel operations with a network of dozens of communities across the country, programs for all ages

Judah Ari Gross/eJewishPhilanthropy

Musicians from the Hadar Institute perform at the egalitarian Jewish learning organization's inaugural national Shabbaton at the Nir Etzion Resort in northern Israel on March 27, 2025.

NIR ETZION, Israel — The Friday-night prayer service at the inaugural Israeli national Shabbaton of Hadar, the New York-based egalitarian house of study that is now expanding its footprint in the Holy Land, featured a twist on the traditional mechitza, or divider.

The so-called “tri-chitza” — a portmanteu of tri- and mechitza — put men on one side, women on the other and mixed-seating in the middle, where the bima was also located, offering a tangible image of what Hadar is trying to do — break down religious barriers in Israel, particularly those surrounding gender.

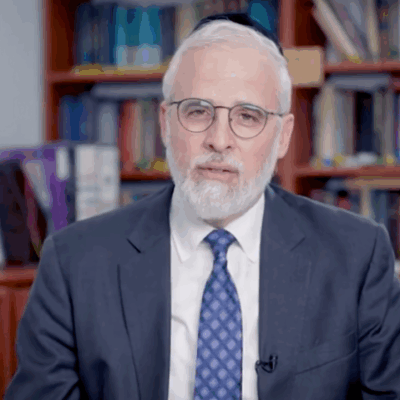

“Hadar can offer that religious landscape that is amazingly still unique in the Israeli context. We are really trying to break down the hard barriers between the easy splitting of the society between religious and secular. [There are] people who have a commitment to openness and tolerance and a commitment to being religious, and they can find a home in Hadar,” said Rabbi Elie Kaunfer, one of Hadar’s co-founders.

The roughly 350 people who attended Hadar’s inaugural national Shabbaton last weekend came from Jerusalem, where Hadar in Israel is based, but also from Beersheva, Tel Aviv, Zichron Yaakov, Haifa, Efrat and more. Some were graduates of Mechon Hadar and for others this was their first time participating in an event organized by the group. They mainly spoke Hebrew, but also some English and French. They ranged in age from 2 weeks to 94 years old.

In attending the Shabbaton, they were taking part in the next phase of the organization’s strategic plan, which is looking to create and strengthen a network of like-minded communities throughout the country in order to create the infrastructure needed to allow for more progressive and egalitarian religious life.

“The goal is to allow someone to live this way of life from birth to death,” Rabbi Avital Hochstein, president of Hadar in Israel, told eJewishPhilanthropy shortly before Shabbat last week. “It should eventually go without saying that the mother will be able to be present at the Zeved Habat” — a naming ceremony for girls during Torah reading, when women in traditional services are in a separated section — “and that there will be synagogues that are egalitarian and that in daycare the girls will not just hand out the tzitzit to the boys” — a common practice in most religious preschools — “but take part in the prayers and so on and so forth.”

The Hadar Institute opened its doors in 2006, founded by Rabbis Elie Kaunfer, Shai Held and Ethan Tucker — today the organization’s co-presidents and CEO, dean and rosh yeshiva, respectively. In 2018, Mechon Hadar was established as an Israeli nonprofit, building a beit midrash in Jerusalem, followed by smaller learning centers in Tel Aviv and Beersheva. More recently, Hadar has created a network of some 60 minyanim, prayer communities, throughout the country, from Eshcar in the north to Yeruham in the south, but mainly in the center of the country, particularly in Jerusalem.

Last year, Mechon Hadar developed a five-year strategic plan with the goal of both expanding those existing elements and adding new ones, such as constructing a second “flagship learning institution outside of Jerusalem” and launching a pre-army preparatory program, as well as expanding an existing teenage “moot beit din” program and publishing new books by Israeli staff and translations of English works by Hadar Institute faculty members.

“Our strategic plan has three anchors: One is spreading our religious vision, two is building institutions and three is creating leadership that can have an influence in existing institutions,” Hochstein said.

“This Shabbaton touches each of those three anchors,” she said. “The Shabbaton itself is an institution, and we as an institution are making this Shabbaton happen. Spreading our religious vision is probably the most important — there are people here who have never stepped foot in a room at Hadar, so this expands the number of people who have encountered our religious vision… and within this group there are people in leadership, and this Shabbaton strengthens them and develops them.”

While the goals for the gathering — dubbed “Shabbaton Meshivat Nefesh,” or soul-stirring Shabbaton — were lofty, the three-day program was decidedly relaxed. Guests arrived at the Nir Etzion Resort on Thursday evening, receiving decorated tote bags and colorful schedules, as well as a booklet full of spiritual and practical ideas for preparing for Passover (distributing written materials by Hadar faculty to expose more people to its vision is another part of the strategic plan). From Thursday evening to the end of Shabbat, there were classes and song sessions led by Hadar staff. On Friday, there were also trips to nearby hiking trails and in the afternoon an arts-and-crafts session for children to make flowers out of pipe cleaners for Shabbat. After dinner on Friday night, there was a tish, a gathering around a table full of song, short divrei Torah, snacks and drinks (mainly beer, wine and anise-flavored arak).

“This Shabbaton was such an exciting moment for us because it presents an opportunity for people to come together and experience what that vision would look like in an Israeli context,” said Kaunfer, who flew to Israel for the Shabbaton directly from the Jewish Funders Network conference in Nashville, Tenn., speaking over the phone after he returned to New York a day after the Shabbaton ended.

“Hadar can offer that religious landscape that is amazingly still unique in the Israeli context. We are really trying to break down the hard barriers between the easy splitting of the society between religious and secular. [There are] people who have a commitment to openness and tolerance and a commitment to being religious, and they can find a home in Hadar,” he said.

“In Israel, I think our contribution to the ‘ecosystem’ is strengthening an Israeli religious landscape that provides an alternative to the extremist tendencies in religion in Israel, that there’s a community that values tolerance and human dignity, and part of the expression of that is our commitment to growing gender equality in a religious state.”

Kaunfer explained that for the U.S. Hadar Institute, the Israeli expansion is central to its overall strategic plan. “The vision for Hadar overall is: Having a Jewish world that reflects the values that we stand for and care about be more present and robust,” he said.

“The work that we do in Israel is a critical part of that strategy because any Jewish vision today we feel has to take into account the Israeli audience, which represents almost half of world Jewry,” he said. “That’s why we are really pouring more resources into our work in Israel and expanding that network.”

While the Hadar Institute eschews the designation of “denomination” — which Kaunfer described as a 20th-century notion that is less applicable today and doesn’t match Hadar’s more expansive vision for itself — the strategic plan for Mechon Hadar entails developing all the trappings of a religious movement, with affiliated communities, youth groups, flagship institutions and regular programming for all ages.

Orit Rappel-Kroyzer, the director of Hadar in Israel, said the organization’s “code word” for its physical expansions plans is “Kiryat Shmona,” the northernmost city in Israel whose religious life tends to be more traditional.

“Kiryat Shmona is the code word, it’s the dream, which we say out loud in order to make it happen. Part of the idea is that creating this kind of [egalitarian] religious life requires a community, and it is easier to find this kind of community in southern Jerusalem, and it is more challenging to find these communities in other areas,” Rappel-Kroyzer told eJP, referring to the fact that southern Jerusalem is home to a vast array of synagogues, communities and schools.

In general, Rappel-Kroyzer said that Hadar has been building its network through word-of-mouth and by bringing existing minyanim that have a more expansive view of women’s roles in prayer into the fold.

From there, Hadar looks to provide those communities with resources and advice, as well as to develop those who created them into stronger leaders.

“A lot of time those people don’t think of themselves as leaders. They think, ‘I want a community like this, so I’ll get my friends together and we’ll do something.’ So some of what we’ve done is to bring them together and tell them, ‘You are leaders, let’s all sit down and do something,’” Rappel-Kroyzer said.

Hochstein added: “This is already a big change to their identity. ‘I thought I was a volunteer, now you’re saying I’m a spiritual leader. What does it mean to be a spiritual leader?’”

The expansion of Hadar’s activities and footprint will come with a cost. In the organization’s strategic plan, its annual budget is expected to increase from $1.6 million in 2025 to $2.2 million in 2028, with much of the increase going toward additional staff and program costs.

While the Shabbaton is part of a broad, ambitious strategic plan, Hochstein and Rappel-Kroyzer said the goals for it were more limited.

“For people who miss Hadar, the [Shabbaton] is nourishing, and for people who don’t yet know Hadar, that they know it a bit more — that everyone makes one step forward in their acquaintance with Hadar,” Hochstein said, noting that some participants have never before taken part in a minyan with mixed seat. “Now it will be a little less foreign to them.”

For Rappel-Kroyzer, the goal was about serving as a springboard for further activities for the participants.

“In addition to having good experiences… the Shabbaton should give inspiration for more initiatives like this that we, as an organization, can support,” she said. “Because Avital and I can’t do it all ourselves.”

Mechon Hadar provided accommodations for this reporter and his family.

Add EJP on Google

Add EJP on Google