BOOK REVIEW

With new Haggadah, Rabbi Avi Weiss offers Israel-focused, anecdote-filled view of the Passover Seder

'Haggadah Yehi Ohr: Let There Be Light' offers fresh explanations of the structure of the Seder and its significance

Ben Yehuda Press

'Haggadah Yehi Ohr: Let There Be Light'

With Haggadah Yehi Ohr: Let There Be Light, New York Rabbi Avi Weiss — best known for his religious and political activism — has created a touching, accessible and considerate guide to the Passover Seder, offering fresh analyses of its structure, additional readings and a plethora of personal anecdotes.

Modern Zionism and Israel are highlighted throughout the Haggadah, which Weiss told eJewishPhilanthropy was a deliberate effort to assert Passover’s standing as an Israel-focused holiday. According to Weiss, while Sukkot with its references to harvests is more commonly associated with the Land of Israel, Passover should be as well. “That is one of the themes of the book,” he said. “I think that all through the Haggadah there is Israel.”

Weiss told eJP that he began working on Haggadah Yehi Ohr before the Oct. 7 terror attacks, but that the book took on additional significance afterward. “I started it before Oct. 7, but of course then the war began. We were in Israel and decided to stay. I have been very affected by the war,” he said, adding that he is an “unapologetic religious Zionist.”

“You are so fortunate to live in Israel,” Weiss told this reporter. “I feel I can’t breathe in America anymore. Even with all the darkness now [in Israel], it’s a remarkable time.”

He opens the Haggadah with a statement “in solidarity with the soldiers of Israel,” noting that in the wake of the attacks, Israelis displayed unprecedented levels of generosity.

In Haggadah Yehi Ohr, Weiss provides two ways of understanding the structure of the Seder. He divides it into two sections, a “Children’s Haggadah” and an “Adult Haggadah.” The Children’s Haggadah, he says, comprises the first five of the 14 stages of the Seder, which he describes as “child friendly” and aimed at inspiring children to ask questions (this is also when children are more likely to still be awake at the Seder). The Adult Haggadah mirrors that of the children’s but at greater depth.

In addition, Weiss breaks down sections of the Haggadah into three sections: past, present and future. With the Magid section looking at the Jewish people’s past; the sections from Rachtzah to Barech cementing the holiday’s core concepts through rituals that we perform now; and Hallel, with its psalms of redemption, representing the future.

While Haggadah Yehi Ohr, published by Ben Yehuda Press, is written in an accessible way in terms of its content, which even readers who may not have a deep religious education can understand, the volume is somewhat awkward to use as a book. Printed with a right-to-left orientation — to ensure that the Hebrew of the Haggadah flows naturally — the left-to-right English commentary is forced to follow this unnatural direction. Instead of ending on the page on the left and traveling up the spine to the top of the page on the right, you read the page on the right and then jump to the complete opposite side of the book to continue reading, sometimes mid-sentence. Other mixed Hebrew-English books have dealt with this formatting issue in far more intuitive ways.

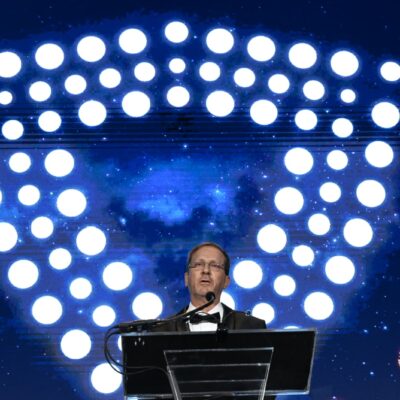

Weiss is the founder of Yeshivat Chovevei Torah for men and Yeshivat Maharat for women in New York’s Riverdale neighborhood, as well as the founder and now-rabbi-in-residence of the Hebrew Institute of Riverdale, which he refers to in the Haggadah as The Bayit — all of them mainstays of the Open Orthodox movement. His Haggadah references these institutions regularly as he pulls inspiration and references from his students and congregants, as well as friends and acquaintances.

In general, Weiss told eJP that his Haggadah was written with a “humble eye,” with him serving as something of a compiler of others’ ideas.

Offering an alternative understanding of the “Son who doesn’t know how to ask” of the “Four sons” section of the Haggadah, Weiss cites Efrat resident Eitan Ashman, who lost the ability to speak after a severe stroke and who compares those who physically cannot ask to Moses, who is said in the Bible to be “slow of speech and slow of tongue” and nevertheless achieves greatness.

Reflecting his Zionism and his decades of political activism, Weiss’ Haggadah ends with Hatikvah, the Israeli national anthem, followed by a section titled “Go and Come in Peace,” in which he reflects on the idea of saying goodbye when we really want to get closer, recalling a congregant who would send her children to school on the bus by motioning to herself. “Even as she said goodbye, she was declaring: I love you, come closer, come closer,” Weiss wrote. “As the Seder ends, we and God do the same – longing, yearning, searching for redemption.”

Add EJP on Google

Add EJP on Google