Opinion

Transformation through trauma

The images of Eli Sharabi, Or Levi and Ohad Ben Ami are seared in our collective consciousness. Their trauma – and that of the other hostages and their loved ones – has reverberations across the ocean as our own local communities take in the horrors. We are connected through this unbearable moment, and also by the collective evocation of our history of trauma.

Trauma, like that which we are seeing today, is raw and real. And we are experiencing it today both directly and indirectly as local and global antisemitism is alarmingly on the rise.

Our current context falls within the familiar storyline of our people reaching levels of safety and prosperity only to suddenly find ourselves in depths of danger and pain. This cycle is deeply embedded in our Jewish collective identity and baked into our very notion of peoplehood. I am not a psychologist or an expert in trauma, but throughout my almost 20 years working in the Jewish community I’ve noticed a particular, recurring theme referenced as tying us together: “intergenerational collective Jewish trauma.”

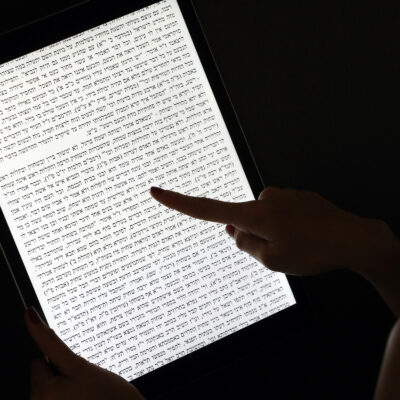

As a people, even in times of security, we do not let ourselves forget these traumas; we revisit them during our holidays, when we pray, in our humor. It’s at the very essence of Jewish culture — with the result that it deeply affects our sense of self and relationship to safety. It impacts our trust, our faith and our understanding of who we are and our position in the world.

While trauma can have a highly variable impact on individuals, it can also lead to patterns of thought, feeling and behavior. Jo Kent Katz mapped out the specifics of intergenerational Jewish trauma, particularly in American Ashkenazi communities, as a tool for healing. She centered two core reactions: terror and a sense of otherness. These reactions can lead to a sense of not belonging and powerlessness; concern for security; an instinct of distrust; a drive for acceptance by way of perfection; and a desire for control and urgency. These responses can be so embedded in our lives that we may not even be aware of them. But once made aware, I’ve found them hard not to see.

In February 2020, I was at the Capitol in Washington studying Torah with U.S. senators and representatives as part of the Jewish Federation of Greater Washington’s partnership with the Shalom Hartman Institute. Yehuda Kurtzer, the institute’s president, asked the group whether they believed we are living in an age of American exceptionalism. Might we be breaking this pattern of Jewish history?

Even some of those Jews who were in top positions of power in the U.S. admitted that they were “waiting for the other shoe to drop.”

These collective patterns have played an important role in our survival, and yet, our trauma response can also lead us to sometimes lose the clarity to discern between fear and perception of danger versus real, imminent danger. It can explain why we can be quick to assume a local incident or word is motivated by hate. I wonder if this trauma response is what drives some to believe that those in our community who critique it must be “self-hating” and “uneducated.” These instincts are understandable in the context of trauma, but perhaps important to overcome if we have any hope of keeping our increasingly polarized American Jewish community together.

Tal Becker addressed the trauma of Oct. 7 when he recently joined the Federation for a conversation with the Greater Washington Jewish community. While post-traumatic stress disorder is widely known, Becker introduced the idea of “post-traumatic growth,” asking how a group can emerge from trauma stronger and more resilient. The Oct. 7 attack has deeply affected Israelis, who are reeling from a pogrom in a country whose very essential identity is to ensure Jewish safety. Becker noted that post-traumatic growth, where resilience and coexistence are possible, will be essential to move forward. For American Jews, the rise in antisemitism has shaken our belief in American exceptionalism, and Becker urged us to use this trauma to more strongly defend our rights and embrace our Jewish identity. Now more than ever we need to stand strong together against all forms of antisemitism and hate.

But I do wonder whether the first step, at both the individual and community levels, is to start by simply being self-aware. When confronted with something — a news event, an interaction — that triggers a response, be aware. Pause and acknowledge. With that awareness, we open the possibility of a choice in how to respond. And with that pause, perhaps we will find new and surprising opportunities — as individuals and as an American Jewish collective.

To be clear, I am not suggesting that we move on from our historical memory. The recounting of our past as a people is core to who we are and how we make meaning. But when we are more aware of and in tune with our responses to those memories, we can ensure we are not allowing those responses to get in our way.

As American Jews, we are in a time marked by an alarming increase in antisemitism in our communities and so much turmoil and pain. While acknowledging the great highs and tragic lows of our people’s past and present, we can also take the time to discern the real from the perceived. We can focus on those enduring characteristics that continually allow us as a people to rise up: the gifts of humor, chutzpah, creativity, compassion, care and everyday wisdom. And perhaps we can turn our trauma into purpose, connection across difference, and growth.

In this I find a lot of hope — something we could all use right now.

Elisa Deener-Agus is the chief of staff at the Jewish Federation of Greater Washington, where she oversees the Federation’s governance and board development, strategic implementation and leadership programs, including the Federation’s six-year partnership with the Shalom Hartman Institute.

Add EJP on Google

Add EJP on Google