Opinion

Donor intent

Tractate Shekalim: A guide for Jewish communal professionals and philanthropists

In Short

As a philanthropy professional, my work during these COVID times has felt ever more urgent

As Rabbi Meir said: When Moses was instructed in the halakhot of the shekel contribution, the Holy One, Blessed be He, took out a kind of coin of fire from under His Throne of Glory and showed it to Moses and said to him: “This they shall give…” (Jerusalem Talmud, Shekalim 4b)

Early in the Tractate of Shekalim, as the rabbis discuss the half-shekel contribution required of every adult male during the times of the Temple, Rabbi Meir conjures a scene in which God demonstrates the commandment to Moses with a coin made of fire. The Kotzker Rebbe, an early 19th century Hasidic leader, explains that the fiery coin represents the passion that the donation embodies; through the act of giving, the cold metal coin is set ablaze. When I came across this teaching during my daf yomi study a few weeks ago, it struck a chord. Having worked in the field of philanthropy for more than two decades, I have seen how passion and commitment transform what could be a purely material transaction into a meaningful and spiritual practice. Indeed, I found the entire Tractate of Shekalim, which could easily be subtitled: A Guide for Jewish Communal Professionals and Philanthropists, particularly relevant and inspiring.

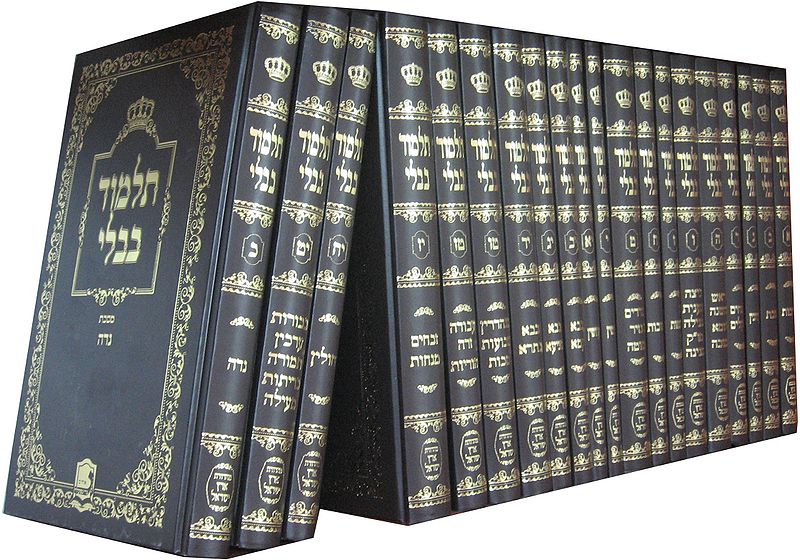

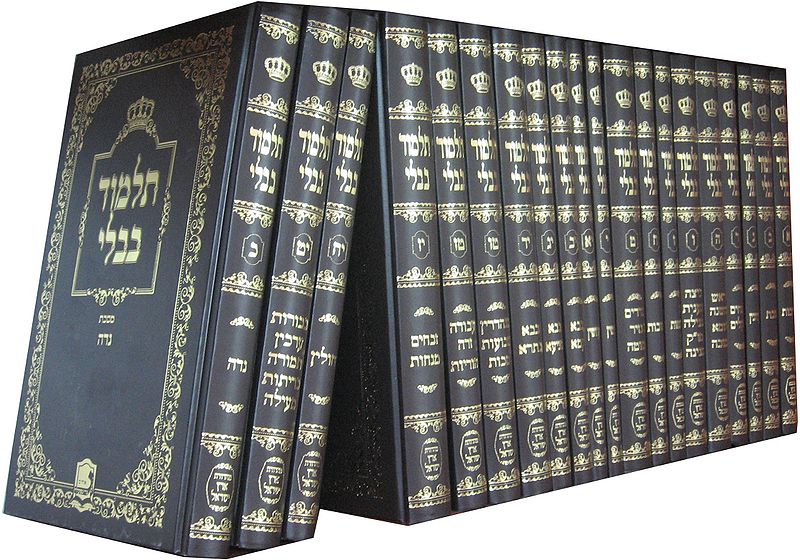

Reuvenk via Wikimedia Commons

In January 2020, I commenced the new cycle of daf yomi, a daily practice of Talmud study created to bind Jews in a textual peoplehood. Throughout the world, every Jew learning daf yomi is literally on the same page with every other person committing to this course of study, eventually completing the entire Babylonian Talmud in 7 ½ years. Little did I know then how important daf yomi would become; during these COVID months at home, my daf yomi became my source of consistency and stability, my “pandemic yoga.” Daf yomi mirrors the rhythms of the pandemic itself. Like time that was passing slowly and quickly all at once, some days would stretch on and the arguments would blend into one another, while on other days, I would gain insights so powerful that they stick with me months later. Sometimes the learning flowed easily, while at other times, I gnashed my teeth as I struggled to comprehend — the sameness of the routine countered by the variety of the content.

I marked the passage of the time with the completion of the various Tractates – in early March 2020, when my day school and synagogue communities were already in quarantine, I completed the first Tractate of the cycle, Berachot, sharing the Marzipan rugelach I had brought home from Israel with my family, rather than at the big kiddush I had planned. As we learned the Tractate of Shabbat, with its fine distinctions between public and private space and designations of muktzeh (items not to be touched on Shabbat), our own boundaries shrunk to the hyperlocal and we monitored every surface we touched with disinfectant wipes in hand. By the time we moved on to the Tractate of Eiruvin, with its emphasis on shared space, both real and imagined though beams and strings, the pandemic had made clear how much we lose when the shared spaces our communities require are suddenly taken away from us. And finally, over the past few months, the Tractate of Pesachim, fortuitously timed to culminate on the eve of the holiday of Passover, reminded us once again how our Jewish lives are intertwined with our communal obligations.

As a philanthropy professional, my work during these COVID times has felt ever more urgent. The trustees of the foundation where I work authorized us to allocate significant emergency funding above our usual payout rate and my team and I, both in Israel and the United States, sought opportunities to meet needs: emergency aid to hospitals and medical clinics; support for isolated seniors; funding to alleviate food insecurity; and grants to meet operational shortfalls. And here too, daf yomi accompanied me. As we worked to understand the interconnected obstacles that make it so challenging to address increased food insecurity when supply chains and volunteer networks no longer functioned, I learned that Jewish tradition already deeply understood how difficult it is to provide food for the hungry. The Talmud in Shabbat 53b describes a poor widower who, unable to feed his infant, miraculously grows breasts to nurse the child. While the rabbis debate whether this was evidence of the man’s honor or dishonor, I nodded in recognition that the rabbis appreciated how reversing the very laws of creation was an easier possibility than creating food out of nothing.

And then we began the Tractate of Shekalim, and day after day, I found my contemporary experiences in the Jewish philanthropy world mirrored in those that transpired millenia ago. Although technically an obligation, the Talmud understands the half-shekel contribution to be less a tax and more a holy act of donation, one that renders each male equally responsible for the communal offerings of the Temple service around which Jewish society revolved. While sacrificial animals, oil and wine libations, and incense feel foreign, the commitment of the people was familiar. The Talmud describes that there were thirteen shofarot, collection horns, each designated for a particular type of public or private offering; while one each sufficed for the specific private offerings, they required 6 horns to hold the donations for the communal offerings. This dedication to communal needs corresponds to contemporary Jewish donors who, during these COVID months, took responsibility for the survival of our Jewish communal infrastructure – with their individual donations to summer camps, health and human service organizations, day schools, synagogues, JCCs and federations.

Ensconced within the rabbinic debates and tales, I found familiar concepts and dilemmas. Once the half-shekel is designated it can only be used for sacred purposes. But what was considered sacred? Tangible items, including animals and oil, could clearly be sacred, as were the stones that paved the Temple courtyard, but could sacredness extend to the intangible work of the artisans who hewed the stone or baked the shewbread? Could the half-shekel pay their wages? This resonated with field-wide conversations about funding administration and overhead versus program-specific expenses, with Rabbi Akiva viewing even the intangible labor as sacred (and thus payable with sacred coins), and Ben Azzai arguing against their use for this purpose. For the rabbis of the Talmud, money, and especially consecrated money, is not fungible: it must be used for the purpose for which it was intended. Whether money explicitly consecrated for the Temple or charitable funds collected for a specific purpose, donor intent matters: money collected to free a captive must be allocated to freeing captives; money collected for the poor must be allocated to the poor. Contemporary questions around donor restrictions, general operating support and even what to do when a Go Fund Me page exceeds its goals take on new meaning in this Second Century light.

Following a discussion of the Chamber of Secret Gifts, a room in the Temple into which people would secretly deposit money and from which those in need could secretly take, the rabbis share several stories that demonstrate to what extent one must consider the dignity of the charity recipient and listen and respond to their immediate needs – lessons that can serve us well as the philanthropy world moves toward a more grantee-centric approach.

In stark contrast to earlier stories about anonymous giving, the Talmud then shares the stories of Rabbi Hama bar Hanina and Rabbi Avun, who proudly show off their capital contributions (a synagogue building and gates of the study hall). They are rebuked by colleagues who argue that the money would have been better used had it been given directly to the people studying. The criticism is not surprising, given that the Talmud is consistently biased toward actions that expand the study of Torah; but I could easily imagine a contemporary debate about how to invest philanthropic resources: in a beautiful building designed to attract Jewish participants, or in the resources to ensure that Jewish programs will take place in that building. Both equally valid perspectives have their roots in the actions of the rabbis centuries ago.

Shekalim begins with a list of the responsibilities that the agents of the court and the Temple were required to begin in the month of Adar in excited anticipation of the coming Spring, including the collection of the half-shekel. With vaccine availability increasing nationwide, Spring is dawning with a profound optimism that we might be nearing the end of COVID. And daf yomi once again demarcated my time, as I prepared with excited anticipation for my own upcoming Spring, with my first and second doses of the COVID vaccine neatly bookending my three weeks of studying Shekalim.

Following the destruction of the Temple, the rabbis created a set of communal structures – primarily the synagogue and the beit midrash – and transformed the Temple service into a service of the heart and mind. At the same time they kept alive the vision of the Temple through the details they recorded in the Talmud. But as I reflect on Shekalim, it is not the minutiae I remember, it is the people: the priests, ankle deep in sacrificial blood; the artisans, guarding the secrets to the incense; the shekel collectors, travelling the country; and the half-shekel givers, including the women and children who were not obligated to give, but did so anyway. Today, the Jewish community– its individuals and its institutions – continues to be the replacement for the Temple and it is the people, whether through their fiery coins or their fiery passions, that keep the vision alive.

Dr. Idana Goldberg is Chief Program Officer, The Russell Berrie Foundation.