Matan Torah

Sight unseen, Alfred Moses bought one of the world’s most expensive books to fill Jews with pride

eJewishPhilanthropy spoke to the former ambassador and one-time president of the American Jewish Committee about his purchase of the Codex Sassoon for ANU: Museum of the Jewish People

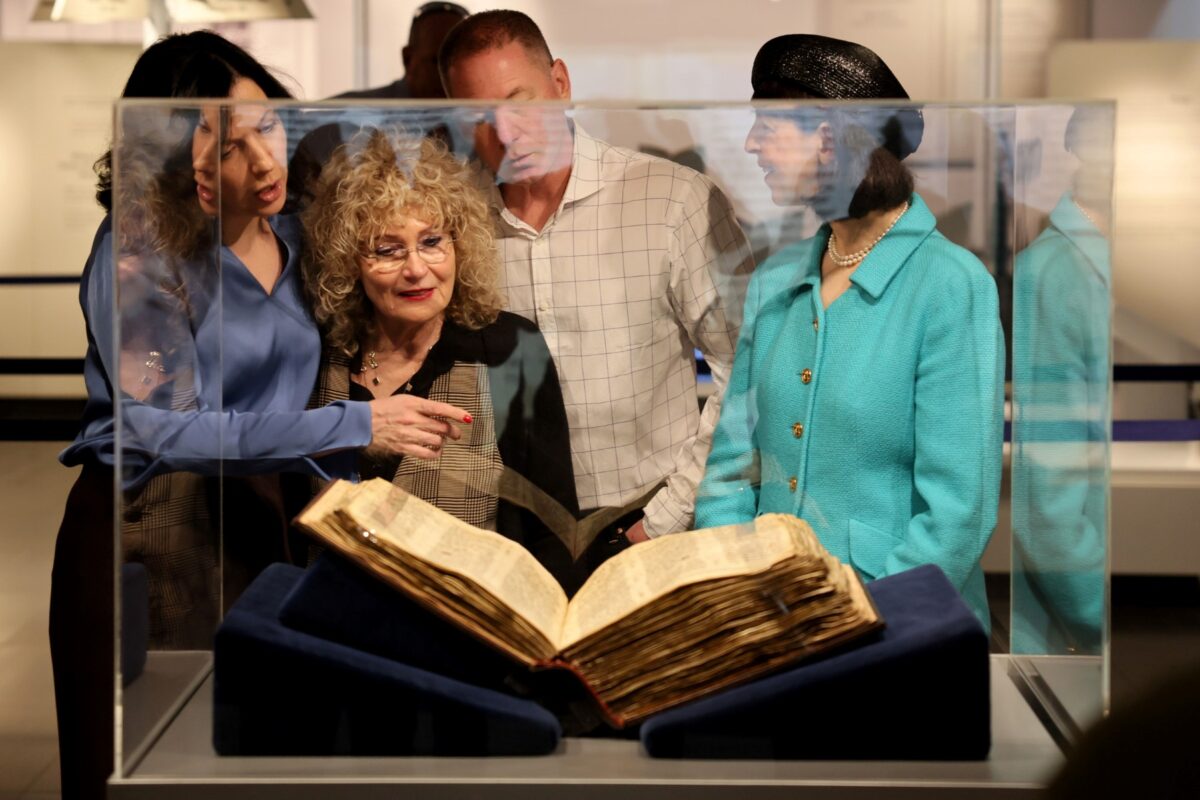

Courtesy

Alfred Moses

When investor Jacqui Safra put the Codex Sassoon, a 1,100-year-old near-complete copy of the Tanakh, up for sale in mid-February, Alfred H. Moses – a longtime attorney, former U.S. ambassador to Romania and a former president of the American Jewish Committee – decided, without too much deliberation, that he wanted to buy it. And Moses knew where he wanted it to go: Tel Aviv’s ANU: Museum of the Jewish People.

Last week, at the auction at Sotheby’s in New York, Moses did just that, bidding $33.5 million. Adding in the additional fees and costs, he ended up paying $38.1 million for the Codex Sassoon, also known as “Codex S1” and “Safra, JUD 002,” making it the most expensive bound book ever purchased, or the second-most when accounting for inflation (after an original copy of the Book of Mormon that was sold in 2017). Moses had never seen the Codex Sassoon when he purchased it, and even now, after paying $38.1 million for it, he still hasn’t.

The Codex Sassoon is a weighty 396-page tome written sometime around the year 900 C.E. in either the Land of Israel or Syria. Despite its age, it is in remarkable shape, missing only 12 pages – eight of them from the Book of Genesis and the rest from the very front of the book, which likely contained additional, non-biblical information. The codex derives its name from one of its previous owners, the bibliophile David Solomon Sassoon, who purchased it in 1929. His descendants sold it in 1978 to the British Rail Pension Fund, who sold it 11 years later to an anonymous dealer who then quickly sold it to Safra. Over the years, it has been scanned and studied by scholars, but it was only once put on public display, at the British Museum in 1982.

It has only two near-peers: the famed Aleppo Codex, which was written around the same time but has far more pages missing, and the Leningrad Codex, which is slightly more complete than the Codex Sassoon but is also roughly 100 years younger. All three are written in what’s known as Masoretic text, which includes not only the words of the Bible – like a Torah scroll – but also the punctuation marks and pronunciation guides in the margins. It is how we know that we are reading the Bible the same way today as Jews did more than a millennium ago.

At $38.1 million, the Codex Sassoon is far and away the most expensive item to ever be donated to ANU. Though it was briefly displayed at the museum earlier this year, in the weeks preceding the auction, ANU will have to make major investments, particularly in terms of security and insurance, in order to permanently display the codex.

This week, eJewishPhilanthropy spoke with Moses to understand why and how he made up his mind to purchase the codex for ANU. Below is the transcript of the interview, which was conducted over Zoom.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and grammar.

Judah Ari Gross: Like the rest of the world, we saw your purchase of the codex last week. How did you get involved? Why did you decide to make this gift specifically to ANU?

Alfred Moses: Well, I only bought it because of ANU. I wanted it to be somewhere where it would be available to the Jewish people, not in some rich person’s bank vault. I had been working with ANU for some years. I thought it was the right place. So it’s now available for everyone to see.

JAG: Why specifically the Sassoon Codex, what about this book spoke to you?

AM: Well, the codex is the oldest Hebrew Bible that we know of. It’s almost a complete Tanakh. It’s missing some 10 pages in parts of Bereshit. Otherwise, it’s complete with notes and nekudot, with the punctuation. So it’s a treasure, it’s a treasure for the Jewish people.

JAG: When did you find out that the codex was going up for sale?

AM: I can’t tell you precisely, probably about six weeks ago.

JAG: That’s a pretty major purchase to make in just six weeks. What was the thought process that went into it? What were your considerations?

AM: Well, it is a major purchase, but you either do it or you don’t. I decided to do it. It doesn’t take long to make a decision.

JAG: Still though, this is going to be an order of magnitude more expensive than anything else that ANU currently has in its collection. How did you make the almost spur of the moment decision to say, ‘Yes, I’m doing this.’

AM: That’s been my whole life. I think about it, I decide, and I go. I’m not one who anguishes a great deal. Ani lo mitlabet (I don’t hesitate).

JAG: How exactly did this purchase work, did you approach ANU saying, ‘I want to buy this and put it in ANU,’ or did they come to you, asking you to buy it on their behalf?

AM: No, no, I went to them. I told them that I hoped to buy it. And if I could, it would go to ANU. And they were thrilled. No, it was my idea, not ANU’s.

JAG: And have you seen it? Have you held it?

AM: I’ve never seen it.

JAG: You’ve never seen it?

AM: No, I have not. I’m going to New York next week, and I will see the codex with Sharon Mintz, who’s the expert. She’s the consultant on Judaica at Sotheby’s.

JAG: But what was it specifically about the codex? There are plenty of significant items of Judaica in the world that could be given to ANU or other causes. So what was it about this book specifically?

AM: It’s the oldest Tanakh in existence. It’s almost complete, written beautifully on parchment, on sheep skins. There’s nothing like it in the world. There are two other old codices, the Leningrad codex, which is in Leningrad, and the Aleppo codex, but they’re both more recent than Sassoon Codex.

JAG: And why ANU specifically?

AM: Well, I wanted to be in a museum in Israel that was open to all the Jewish people and was built for the Jewish people. I can think of two other possible institutions: the Israel Museum, but that belongs specifically to [the State of] Israel, and then there’s the National Library, which is also Israel’s. I want this to be for all the Jewish people, those living in Israel, of course, but also those living outside of Israel.

JAG: You’ve had a relationship with ANU for several years, how did that happen?

AM: I got involved when it was still Beit Hatfutsot. A close colleague of mine was the American representative of Beit Hatfutsot in the United States, Shulamit Bahat. She persuaded me to come with her, and I started to work to rebuild Beit Hatfutsot, so that it was no longer the Museum of the Diaspora, but now the Museum of the Jewish People. I like to think it was my idea. But Shula says it wasn’t. (chuckles)

JAG: From what I understand from ANU, this is going to be by far the most expensive item that they’ll have in their collection, which will bring with it associated costs for insurance, for security, for things like that. Are you planning to help them with those costs going forward or are you more of the mindset that the book is in their hands to care for now?

AM: More of the latter, but I think their attendance will increase sharply and will cover the additional expense. I think tens of thousands of Jews from all over the world will now come to ANU to see the Sassoon Codex and take pride in the history of our people.

JAG: And what do you hope that those thousands of Jews get out of this, get out of seeing the book?

AM: I hope that seeing the book will give them a sense of the history of the Jewish people. This is the foundational book of our civilization, of our religion, but also our broader civilization. It encompasses the first 2,000 years of Jewish history. And it’s the only book that’s close to complete. And there is no book that is as old as the Sassoon Codex. So I think people will look at it with pride and, if I may say so, with awe.

JAG: Why is that so important for you? Why is that something that you wanted to have such a role in?

AM: It’s in my blood. It’s been my whole life. I went to heder (religious school) as a boy. I went to synagogue with my father. I’ve been a proud and active Jew all my life in school, in the military service, in government service, in private law practice, in my life. So this is just one more part of it.

JAG: Do you see this as part of your legacy?

AM: I don’t think it’s for a legacy. I think it was something that I was fortunate enough to be able to do. I’m a lucky guy to be able to do this.

JAG: The timing of this purchase is fitting, coming just before the holiday of Shavuot, where we celebrate Matan Torah, the giving of the Bible.

AM: Well this is my Matan Torah.