TIMELY EXHIBIT

L.A.’s Wende Museum opens a new center for Russian-speaking Jewry

The museum is dedicated to commemorating and understanding the Cold War

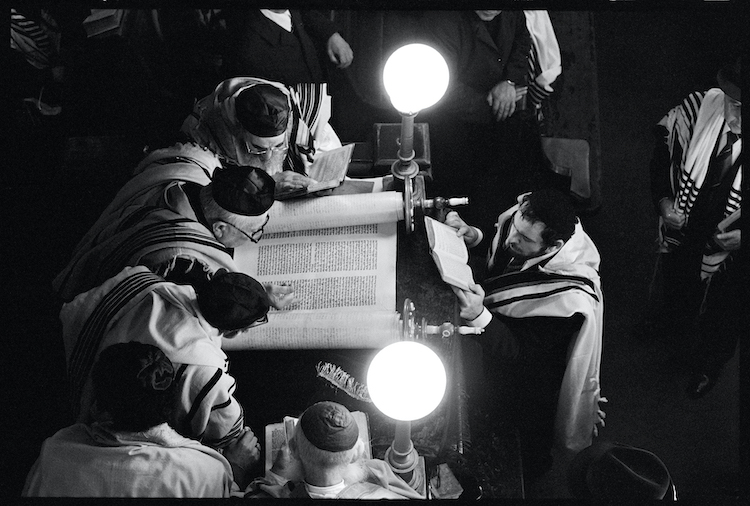

Bill Aron

Bill Aron

The recent death of Ida Nudel, the celebrated dissident who endured Siberian exile in order to immigrate to Israel from the Soviet Union, triggered both grief and anxiety among the dwindling community of dissident activists, said Alexander Smukler, a Soviet-born businessman who as a young man in the 1980s helped lead the refusenik movement of Jews refused permission to emigrate. The opening of the Robin Center for Russian-Speaking Jewry at the Wende Museum last month has helped to ease survivors’ fears that their stories will die with them.

“We are getting old, and more and more of us are departing from this world,” Smukler told eJewishPhilanthropy. “We lost Nudel, so I think it’s the perfect timing.”

Raised by secular Communist parents, Smukler first gained an inkling that Jewish culture existed in the Soviet Union when he glimpsed people wearing Stars of David on the beach in the summer of 1977. He ingratiated himself with them by playing chess — he was a highly skilled player — and read a contraband copy of Leon Uris’s Exodus. He eventually applied to immigrate; was refused and became one of a small group called the Mashka, which coordinated Hebrew teaching and care of refuseniks, who were often ostracized and deprived of their livelihoods, and their families.

Smukler has contributed materials to the museum, and is a member of its Soviet Jewry Archives Advisory Committee. The center is the brainchild of Edward Robin, who with his wife, Peggy, is also funding it. The Wende is both an art museum and an archive. It will digitize the museum’s collection of samizdat — printed materials banned by the state — that are a primary source of information about the world of Soviet Jewry and the refusenik movement.

“The refuseniks had lives,” Robin said. “And not all of them were public figures.”

A former chairman of the National Conference on Soviet Jewry, Robin co-chaired Freedom Sunday for Soviet Jews, the 1987 march that drew 250,000 people to the National Mall in Washington, D.C. He and Peggy traveled to Moscow to help refuseniks by teaching language skills and giving them goods to sell on the black market.

The stories of the American Jews who traveled to Russia on missions to help Soviet Jews have been much-told, Robin said, while the world knows less about the Soviet Jews who needed that help.

“Everybody thinks their trip report is a document of historical importance, but that’s not true,” he said.

The pandemic played an inadvertent role in the conceptualization of the center, Robin said. He had introduced Bill Aron, a friend and photographer known for his photos of Soviet Jews, to staff at the Wende, who scheduled an exhibit of Aron’s work. The exhibit was delayed by coronavirus pandemic. At the same time, Robin began to realize the prominent role Russian-speaking Jews were playing in the museum’s oral historical witness project, and he realized that Soviet samizdat was at risk.

He created the center to preserve those materials. The Aron exhibit will finally be mounted on Nov. 14 as “Soviet Jewish Life: Bill Aron and Yevgeniy Fiks,” the center’s inaugural event.

Both the center and the exhibit are a milestone in the ongoing work of giving the history of Russian-speaking Jews the attention it deserves, said Marina Yudborovsky, CEO of the Genesis Philanthropy Group (GPG). The strengthening of Jewish identity among Russian-speaking Jews is one of GPG’s three primary program areas.

“It’s been a good 30 to 50 years, and it’s exactly that timeline when things stop being recent news and become history,” said Yudborovsky. GPG is “incredibly excited” that the Robin Center isn’t their initiative, because that suggests that it’s not only Russian-speaking Jews who recognize the importance of the Center’s artifacts.

Robin said the museum’s “hybrid” nature makes it the ideal location for the center. It’s a scholarly institution that emphasizes outreach through programming and encourages the public to draw connections between its collections and current events. The Aron and Fiks exhibit will be accompanied by public programs and educational workshops.

“They use history to talk to the present,” he said.

GPG is funding some of the programs that will happen under the auspices of the Robin Center, Yudborovsky said.

The role that the struggles of Russian-speaking Jews played in the fall of the Soviet Union is inadequately understood, she said, and both the Wende Museum and the Robin Center will help rectify that.

“We all always felt like we were victims of the Cold War, because the door was open and then closed, and it depended on the political situation in the world,” Smukler said.

Now Smulker hopes the center will convey a “simple message” to younger people — that they shouldn’t take being Jewish for granted, and should give careful consideration to what their faith means to them.

“What makes them Jewish, even if they aren’t a religious person?” he asked. “I want them to understand what we went through, and how we discovered that we were Jews.”