Opinion

Jewish peoplehood

Jews have more than an obligation to repair the world

In Short

There is some truth to the criticism that the Reform movement seems to focus on tikkun olam, not as an expression of Jewish peoplehood, but at its expense. Judaism is both particular and universal. Social justice divorced from the centrality of Jewish peoplehood isn’t Jewish universalism; it is just universalism.

Why do Reform Jews seem to emphasize tikkun olam over and at the expense of every other Jewish value?

This past week an old friend of mine interviewed me for his radio show. He and many of his listeners are Orthodox Jews. I’d assumed our discussion would be friendly banter, but my friend zeroed in quite aggressively on what he perceived to be the weaknesses of the Reform movement.

In particular, he pressed me on why we so emphasize tikkun olam, the Jewish obligation to repair society — to care about and act upon — the moral flaws and inadequacies of the world around us, outside the Jewish community.

The answer lies in last week’s Torah portion, “Vayera,” which tells us about the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah. God is portrayed as deliberating, perhaps arguing with Himself: “Shall I hide from Abraham what I intend to do?”

In one of the most remarkable passages in all of religious literature: God invites Abraham to debate. And Abraham takes up the challenge and utters among the most eloquent and revolutionary words in the entire history of religious thought: “Will not the Judge of all the Earth do justice? Will you kill the righteous along with the wicked?”

Why should Abraham care about the inhabitants of Sodom and Gomorrah? But he does. If you want to understand the Jewish people’s stubbornness, our argumentative nature, our insistence on justice, and why Jews seem to be overrepresented in every social cause under the sun, look no further than: “Will not the Judge of all the Earth do justice?”

Some non-Jewish theologians view this passage as the prime example of the downfall of Man: the hubris that a creature of flesh and blood can dare to challenge God. But the whole point of the passage is that Abraham argues with God — and God welcomes the debate! Judaism is not a one-way street where God commands and people obey. Rather, God wants protest for the sake of what is right.

Had the point been obedience, then the story would have ended with Abraham punished or smitten, and with a cautionary admonition. But the point of Judaism is to develop a kinship with all human beings, to protect the weak and to feel a sense of collective responsibility. God searches for the Abrahams of the world — not just good people, but good people who are willing to fight for others. That’s why we emphasize tikkun olam, the repair of society’s injustices. It is not simply a Reform value; it is a Jewish value.

And so I told my friendly radio interrogator: our synagogue is proud of our emphasis on tikkun olam. We’re proud of our pantry that distributes food to the needy every Shabbat. We’re proud of our men’s shelter that, before the pandemic, allowed us to host 10 homeless New Yorkers nightly. And we’re proud of the many other initiatives devoted to people in need — irrespective of race, religion or creed — organized by our congregants, who volunteer in pursuance of Jewish values. For them and for us, tikkun olam is an outgrowth and an expression not of Reform Judaism, but of Judaism.

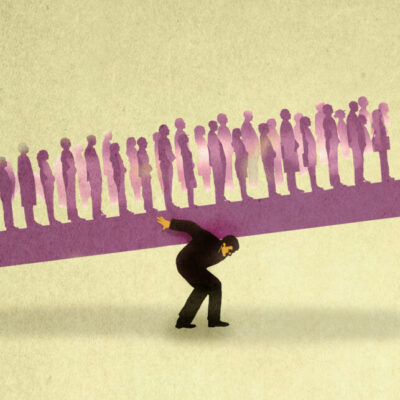

But my Orthodox friend did raise a very good point: why do Reform Jews seem to emphasize tikkun olam over and at the expense of every other Jewish value? Why does it seem that tikkun olam is the only value that Reform Jews speak about? Now that’s a critique that resonates with me. I myself have cautioned that we often give the impression that Judaism is only tikkun olam: that Judaism is only universal aspirations — and has nothing to do with our own particular people.

We need to be careful in striking the right balance. All of us, including the Jews in the pews, rabbis and leaders of our movement must do deeds and speak words not only of the universal values embedded in tikkun olam, but also of Klal Yisrael, the principle of the centrality of the Jewish people. This, too, is at the very heart of Judaism. In fact, it was introduced to Abraham hand-in-hand with tikkun olam: “Abraham, I will make of you a great nation and I will bless your nation, and through the Jewish people, all the families of the earth shall be blessed.”

Jewish peoplehood — our obligations to one another — is the axiomatic assumption of Judaism. “Kol Yisrael areivin zeh ba’zeh” — “all Jews are responsible one for the other,” the Sages teach.

From the beginning of Jewish time, there was always a healthy tension between the centrality of the Jewish people and our universal aspirations. If we reject Jewish peoplehood in deeds, through words or by what we do not say, then what is left is not Jewish universalism; it is just universalism.

Hosea was not Hegel. Micah was not Mill. Jeremiah was not John Locke. All of the Hebrew prophets — every last one of them whose universal principles we love to quote — were of the Jewish people, by the Jewish people and for the Jewish people.

Amos, who stood for the universal ideal of justice — “Let justice roll down like water” — was the same prophet who said: “I will restore My people Israel…and I will plant them upon their own soil, nevermore to be uprooted.”

Isaiah, who taught the universal concept of attending to the weak — “The poor and the needy seek water…I will not forsake them” — also said: “But you, Israel… I have appointed you a covenant people, a light to the nations…”

And Micah, who insisted on the universal principle of peace — “they shall beat their swords into plowshares” — concluded his book: “You will keep faith with Jacob, loyalty to Abraham, as You promised on oath to our ancestors in days gone by.”

Judaism commands us to repair the world, but never at the expense of our duty to our fellow Jews. To the contrary, tikkun olam is an outgrowth, an obligation rooted in Jewish peoplehood.

Ammiel Hirsch is senior rabbi of Stephen Wise Free Synagogue on New York’s Upper West Side.

Add EJP on Google

Add EJP on Google