TURNAROUND MODE

YIVO is professionalizing, growing and reviving a lost world

The institute is finishing its biggest-ever project — the digitization of 4 million pages

Archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research

Archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research

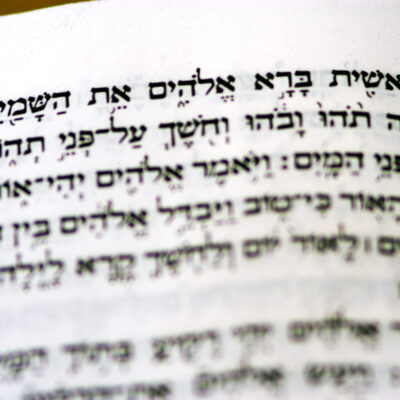

One digitized page at a time, until four million pages of books and other documents are clickable online, the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York is capturing for a new generation what life was like in the Jewish intellectual center of Vilna, Lithuania, before the Holocaust.

The effort, called the Edward Blank YIVO Vilna Online Collections Project, is salvaging Jewish memory at a time when those who remember that long-ago world fade away. “We’re talking about a lost civilization here,” said Glenn Dynner, a professor of religion at Sarah Lawrence College who has drawn on YIVO’s archives in his scholarship.

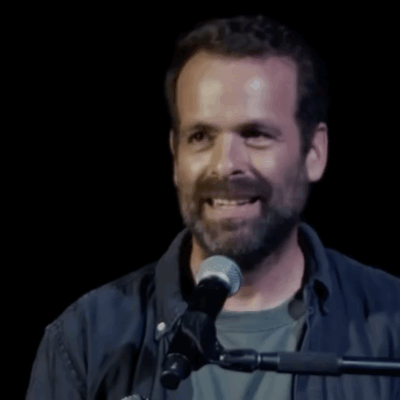

YIVO, which is now in an unexpected phase of growth and increased revenue, is in the final stages of finishing the digitization project. And it is becoming a more professional operation, YIVO CEO Jonathan Brent told eJewishPhilanthropy.

“We have had a rocky financial history. There was instability on the board of directors and churn among the staff,” said Brent, who came to YIVO in 2009 from Yale University Press in New Haven, Conn., where he served as editorial director. “We had a reputation of not being able to complete a project on time, or on budget.”

All of that is changing.

When YIVO Institute for Jewish Research was created in Vilna, Lithuania, in 1925, its founders had planned to offer advanced degrees in Yiddish studies. World War II forced them to relocate the institute in New York, where it frequently struggled to secure adequate funding, even into the early 2000s. Now, the dream of offering a master’s degree has been revived, thanks to a period of growth in support and an expanding public reach, Brent said.

When it was founded, YIVO was embedded in the world of East European Jewry that was destroyed by World War II. Today, it still serves as a center for culture and scholarship, but also as a repository of books, documents and other artifacts.

Brent said he is hoping to start improving YIVO’s professional image with its execution of the Edward Blank YIVO Vilna Online Collections Project. It will digitize four million pages of books and other documents.

“The Vilna project is a way to keep alive for future generations the Ashkenazi Jewish history, culture and way of life before the Holocaust — the one my parents knew and brought with them from Eastern Europe, but which has been fading with each new generation,” Blank said.

YIVO will complete the Vilna project in January — on time and without going over its $7 million budget, a first for a project of this size, Brent said.

Blank is the lead funder, and the project received gifts in the millions and hundreds of thousands of dollars from individuals and foundations, including several anonymous donors, Sandra Pine, Mildred Suesser, the Kronhill Pletka Foundation, the Righteous Persons Foundation and the Slovin Foundation. The Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, the Institute for Museum and Library Services and the National Endowment for the Humanities.

YIVO launched the Vilna project in 2014, and it’s being completed at a time when the institute is posting increases in revenue, donors and users of its programs.

Like other cultural institutions, YIVO experienced a surge in interest from people at home due to quarantine orders during the pandemic, Brent said.

Between 2019 and 2021, unique visitors to YIVO’s website more than doubled, from 51,000 to 130,000. Registrations for its self-paced online courses about Ashkenazi culture, including food and folklore, rose from 5,000 to 25,000.

Largely as a result of this broader exposure, the number of individual donors has increased by 61%, from 1,614 to 2,591. Revenue has grown from about $2 million to about $2.4 million, about 19%.

YIVO has used the additional funds to expand its staff, hiring eight people in the last three years, with an emphasis on experts in digital technology who will be able to reach both a younger audience and people who don’t read the languages in which YIVO’s materials are written — mostly Yiddish, but also Polish, Romanian and other European languages.

“You can’t understand the Holocaust without understanding Jewish life in Eastern Europe,” Dynner said. “And you can’t understand the immensity of that loss until you reconnect with that world.”

A professionalized YIVO is making that world more accessible, he added. “YIVO used to be very haphazard and informal, which had its own charm but it can be very frustrating, and now they’ve turned a whole page.”

The YIVO Bruce and Francesca Cernia Slovin Online Museum, which uses one piece of the institute’s collections and then connects it with other materials to tell a fuller story of Ashkenazi life, is one of the new staff’s signature projects, Brent said.

The museum’s inaugural exhibit, “Beba Epstein: The Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Girl,” centered on Epstein’s memoir, written in 1932 in Vilna, when she was 11. Virtual visitors to the museum could page through her memoir, and also view photographs of the city, of her summer vacations and of her other experiences. Also included are Epstein’s testimony for the Shoah Foundation — she survived the war in several concentration camps.

“In general, all we have is The Diary of Anne Frank,” Brent said. “This is a girl who goes through the Holocaust in an entirely different way.”

The institute is also planning to embark on another digitization project that will be larger than the Vilna collection, consisting of 3.5 million pages and 25,000 photographs acquired by the Jewish Labor Bund Archives in 1992.

“Thanks to YIVO, our Eastern European history is not dying, it is coming to life. YIVO is our modern-day phoenix rising from the ashes,” said Deborah Veach, a new member of the YIVO board.

As for the master’s degree, it’s true that there are several excellent existing programs, such as one at Harvard University, that view Yiddish culture through literary, historical or other scholarly prisms, Dynner said. YIVO’s offering would be focused on primary sources, which would enable the scholars who train there to become a more direct conduit for American Jews who feel cut off from their past.

“We can show what life really was,” Brent said, “and not just reduce it to a punchline, a joke.”